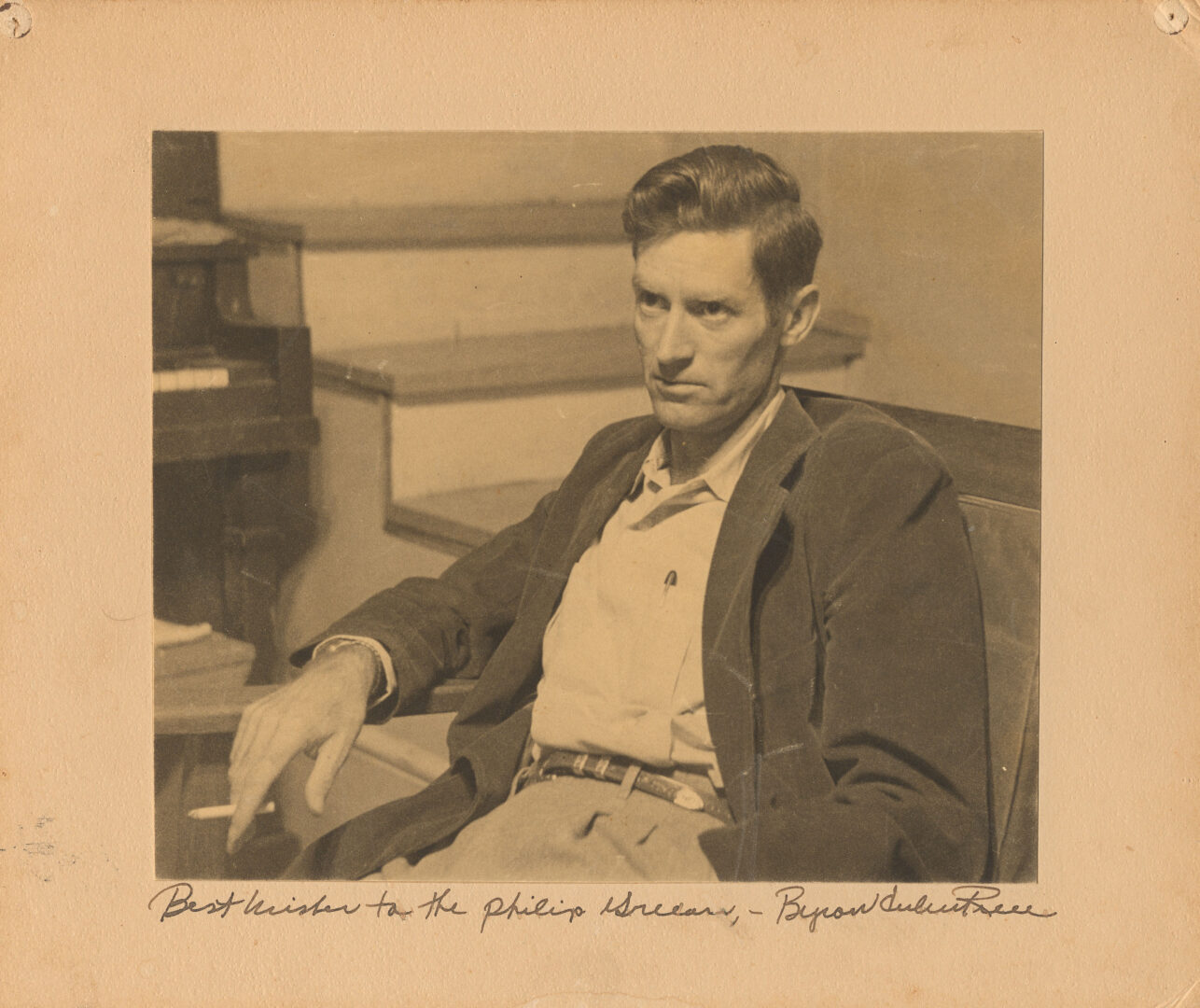

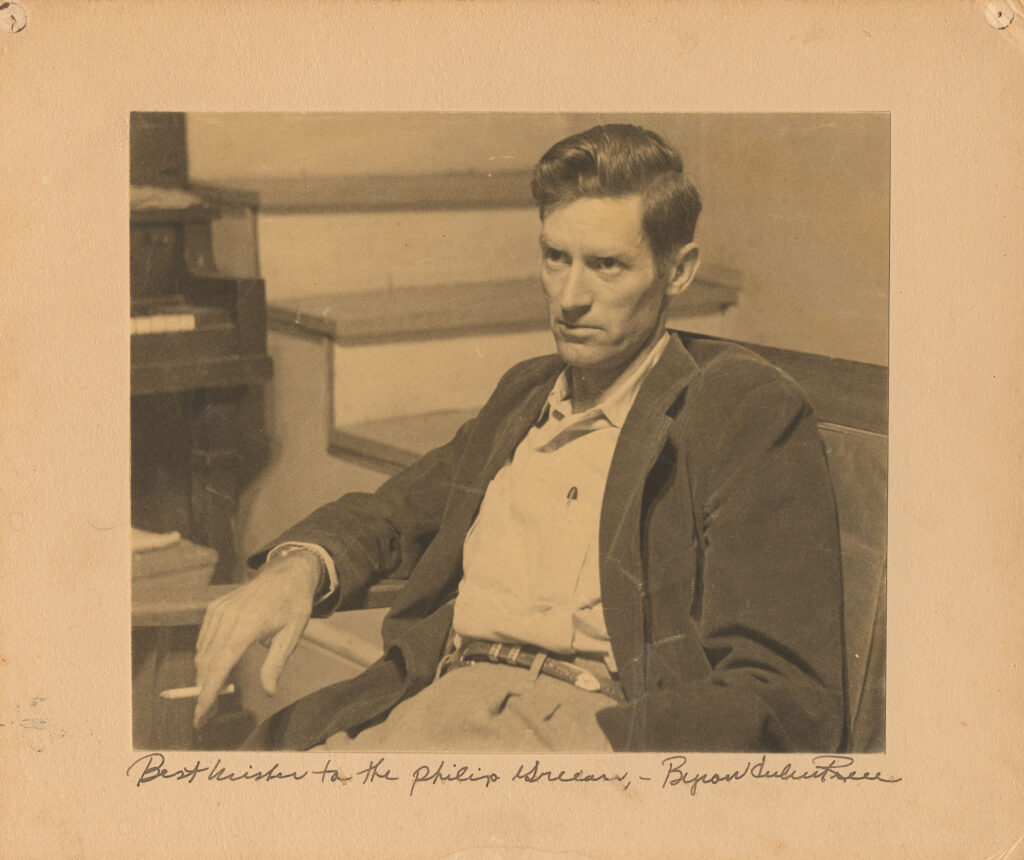

Byron Herbert Reece was the author of four books of poetry and two novels. During his short career he was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize, earned two Guggenheim awards, and served as writer-in-residence at the University of California at Los Angeles, Emory University in Atlanta, and Young Harris College in Towns County. Lauded by the Atlanta Constitution editor Ralph McGill as “one of the really great poets of our time, and one to stand with those of any other time,” Reece never achieved wide recognition. He is known today as the poet whose old-fashioned, finely crafted ballads and lyrics celebrate the life and heritage of the Blue Ridge Mountains.

Reece was born in Union County near Blood Mountain on September 14, 1917, to Emma and Juan Reece. He entered a family that had a long connection to the rural mountain world. The Reeces had lived in the area since the early 1800s and were firmly rooted in the mountain culture. The young Reece, nicknamed “Hub,” showed his talents early. By the first grade he had read the Bible and John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress (1678), texts that would influence his writing. By the age of fifteen, he was publishing poems in the local Blairsville newspaper. After high school he attended nearby Young Harris College, a small, private two-year school, where he found a coterie of friends who encouraged his poetic development.

Reece’s first try at college was short-lived because he needed to devote his time to farming. After working on the family farm for three years, he was able to return with a scholarship and permission to alternate quarters between farm work and schoolwork. Despite these accommodations, he never finished his two-year degree.

Career

In 1943 Reece’s poetic endeavors took a major step forward when Jesse Stuart, a well-known writer from Kentucky, “discovered” him. When Reece’s poem “Lest the Lonesome Bird” appeared in the Prairie Schooner journal, Stuart was intrigued by the ballad skills of the young poet. Stuart asked Reece to show him more poems and persuaded his publisher, E. P. Dutton, to publish the young Georgian’s work. In 1945 Reece’s first collection of poems, Ballad of the Bones and Other Poems, appeared to critical praise.

The next ten years proved fruitful for Reece. While Ballad of the Bones attracted national attention, Bow Down in Jericho (1950) earned Reece a nomination for the Pulitzer Prize. Newsweek magazine featured him in its January 1, 1951, issue. Also during this period Ralph McGill, the executive editor (and later, publisher) of the Atlanta Constitution, became a friend of Reece’s and an advocate of his work.

The first of Reece’s two novels, Better a Dinner of Herbs, was published in 1950. This book and The Hawk and the Sun (1955) constitute all of Reece’s published fiction, though he apparently was planning to write a trilogy of novels about the settlement of north Georgia—plans thwarted by his final illness. Better a Dinner of Herbs narrates the journey of two brothers down from the mountains to the lowlands. Its Old Testament story of love, murder, and retribution takes on the basic tone of the ballad form that dominates Reece’s verse. The Hawk and the Sun narrates events leading up to a lynching in a small Georgia town. Both novels are distinctive and highly original.

Although Reece’s final two volumes of poetry, A Song of Joy (1952) and The Season of Flesh (1955), were also praised, his traditional style was out of step with the Beat and confessional poets who dominated the literary world. Unlike the work of most writers, Reece’s poetry showed little change or development in his four volumes; his poetic forms (most notably the ballad and the lyric), his themes, and his point of view seem to have been fully formed by the time he reached the age of twenty.

Courtesy of Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia Libraries.

Nearly all of Reece’s poetry deals with one of four themes—nature, death, love, and religion. In form the poems vary from short lyrics, sequences of couplets or quatrains, to sonnets and longer ballads. “A Song of Sorrow” summons farmers from their fields to help a woman mourn the loss of her daughter:

O men, come in from the field and the lane

And pray over Sarah’s one daughter again

For she is possessed of a terrible pain.

O men, come in and softly abide

In reverent silence with your knees spread wide

For Sarah’s one daughter has suffered and died.

O men, come in from the field and the plow

And pick at your teeth with the tip of a bough,

And say to her kindly brave words for tomorrow

For Sarah’s possessed of a pitiful sorrow.

“I Go by Ways of Rust and Flame” describes the solitude of the individual in nature. Its speaker “walk[s] alone as all men must / Upon the roads of flame and rust.” Some longer poems concern the traditional content of folk ballads: murder, jealousy, disappointment in love. “Lest the Lonesome Bird,” “Ballad of the Rider,” and “Ballad of the Weaver” are examples. Other long poems retell biblical stories: “Ballad of the Bones” recasts the tale of Ezekiel, and a sequence of poems in Bow Down in Jericho is about the Old Testament figures of David and Jonathan.

Courtesy of Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia Libraries.

One of Reece’s most effective expressions of allegiance to his north Georgia region was his poem “Roads,” which compares the relative virtues of life in the city and the country. The poem comments on the “roofs of iron” and “sheer perpendiculars of steel” that characterize the architecture of the city, along with the hard “streets that bruise the country heel.” In the city, Reece writes,

My heart’s contracted to a stone.

Therefore whatever roads repair

To cities on the plain, my own

Lead upward to the peaks; and there

I feel, pushing my ribs apart,

The wide sky entering my heart.

Reece keeps a narrow focus on the solitary individual’s relationship to the world. The individual, whether looking at nature, death, love, or religion, removes the veil of community to see with his eyes alone; the narrator is not a farmer or a mountaineer or a poet, just a private man alone to face the world, a world that can be beautiful and horrific.

Death and Legacy

Reece’s professional successes were offset by personal strife—farm life was hard, his mother died of tuberculosis, and his father fell ill with the disease. Reece contracted tuberculosis while caring for his parents. During his final years, Reece also taught classes at Young Harris College to earn extra money. On June 3, 1958, he committed suicide at the age of forty. He was found in his office, with Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart playing on the record player and his final set of student papers graded and neatly stacked in the desk drawer.

Courtesy of Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia Libraries.

In 2001 Reece was inducted into the Georgia Writers Hall of Fame. Two years later the Byron Herbert Reece Society was formed, with poet and Reece biographer Bettie Sellers among its inaugural members. In 2004 the Reece family farm was acquired by Union County and leased to the society, which began work to create a museum and interpretive center commemorating the poet’s life and work. A number of Georgia writers, including Sellers, Terry Kay, and Reece biographer Raymond Cook, gathered on the site in June 2008 to mark the fiftieth anniversary of Reece’s death.