The Christian Methodist Episcopal Church (CME Church), formerly the Colored Methodist Episcopal Church, is a historically African American denomination with more than 800,000 members in the United States.

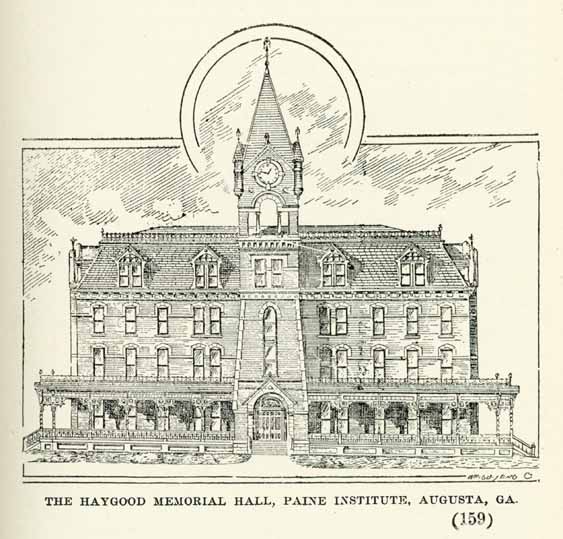

Church polity and theology are consistent with other major American Methodist denominations, and the church participates in such ecumenical organizations as the National Council of Churches. The CME Church supports four colleges, including Paine College in Augusta, and maintains missions in Ghana, Haiti, Jamaica, Liberia,and Nigeria.

Founding and Early History

Between 1860 and 1866, more than two-thirds of the Black membership of the Methodist Episcopal Church South (MECS; later United Methodist Church) left that church to join other Methodist bodies then competing for the membership of freedmen. Most joined one of two independent Black denominations from the North, the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME Church) and the African Methodist Episcopal Church, Zion (AME Zion), where they enjoyed greater autonomy and freedom of expression. In order to prevent further losses, the MECS resolved in 1866 to support the creation of a separate Christian Methodist Episcopal Church Black denomination. Four years later, forty-six Black delegates and a committee representing the MECS convened in Jackson, Tennessee, to establish the Colored Methodist Episcopal Church, the first African American denomination established in the South.

At the inaugural conference in 1870, Black representatives of the new church expressed their commitment to maintaining a cooperative relationship with the MECS, as well as their desire for continuity with Methodist theology and polity. “We most sincerely pray, earnestly desire, and confidently believe,” reads an early resolution, “that there will ever be the kindliest feelings cherished toward the Methodist Episcopal Church, South.”

The CME Church’s decision to maintain close ties with the MECS in the aftermath of the Civil War (1861-65) earned the new church the enmity of northern Methodist denominations hoping to attract new members from among the freedmen. Claiming to be the true redeemers of formerly enslaved people, members of the AME Church, AME Zion, and the northern Methodist Episcopal Church questioned the new denomination’s fidelity to the MECS and referred condescendingly to the CME Church as “the rebel’s church.”

What the CME Church’s critics dismissed as mere paternalism, however, was at least in part a calculated bid to secure the transfer of church property to the new denomination. MECS financial support was based on the condition that the CME Church remain politically neutral. Given its uncertain circumstances, the new church had little choice but to submit to MECS demands. In any case, whether motivated by sincerity or expediency, the CME Church’s decision to forsake political activity for the support of the MECS created a tension within the denomination between paternalism and autonomy that remained unresolved until the twentieth century.

The “Paine College Ideal”

In 1882 Georgia native and CME bishop Lucius Holsey appealed to the MECS for financial support in establishing a school to train Black preachers and educators. The MECS granted Holsey’s request, and in January 1884 the Paine Institute (later Paine College) opened in Augusta. For the CME leadership, the school’s founding was both a source of pride and a testament to the possibilities of interracial cooperation. However, because conservative MECS officials retained financial leverage over the school’s administration, Paine College also helped to perpetuate certain aspects of interdenominational paternalism.

The Paine Institute’s founding established a practical model for interracial cooperation that CME officials would subsequently apply to all aspects of the church’s administration. The “Paine College Ideal,” as it came to be known, ensured that the second generation of CME leaders would stay the course of accommodation and political neutrality established by the denomination’s founders at the inaugural General Conference. Indeed, during the last quarter of the nineteenth century, church elders resisted efforts to forge closer ties with more politically active Black Methodist bodies, preferring instead to maintain a cooperative, albeit subordinate relationship with the MECS. By emphasizing educational uplift, ecumenism, interracial cooperation, and cautious civil rights activism, the CME Church pursued a pragmatic strategy that enabled it to prosper amid the impending hostility of the Jim Crow South.

Ecumenism and Civil Rights

Although they maintained cordial relations with the MECS, CME church officials sought a wider network of support and fellowship during the first half of the twentieth century. By attending international conferences and participating in interdenominational organizations, CME bishops gained exposure to an ecumenical vision that emphasized social reform and the commonalities of Christian identity. Their experiences in the wider ecumenical movement helped strengthen ties with fellow Black Methodist bodies, and CME officials gave serious consideration to merging with the AME and AMEZ churches. Although negotiations for these mergers ultimately failed, the denominations worked closely together in such organizations as the Fraternal Council of Negro Churches, and CME leaders subsequently broadened the church’s focus to include social and political concerns, as well as religious ones.

In 1954, the same year in which the U.S. Supreme Court issued the landmark Brown v. Board of Education desegregation decision, church elders voted to change the denomination’s name to the Christian Methodist Episcopal Church. The name change, which became official in 1956, not only signaled the church’s repudiation of Jim Crow–era racial subordination but also highlighted a more ecumenical emphasis on religious, rather than racial, identity. Thereafter, the church became more active in the civil rights movement, particularly in its support for the legal strategy of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

Although many CME members were slow to embrace Martin Luther King Jr.’s direct-action approach, others actively participated in the civil rights movement. Among the leaders in Georgia were Joseph A. Johnson, a CME minister and theologian who accepted a position at the Interdenominational Theological Center in Atlanta in 1960. Elected bishop in 1966, Johnson explored the relationship between the Black church and social activism in his writings. Donald Hollowell, a prominent civil rights attorney with offices in the Sweet Auburn district, was a member and lay leader of Atlanta’s Butler Street CME Church. During the Albany Movement of 1961-62, Hollowell served as the attorney for both King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. Ruby Doris Smith Robinson, an active CME member and the daughter of a CME minister, emerged in 1960 as a leader of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee while attending Spelman College in Atlanta; she organized sit-ins and demonstrations to protest segregation in the city, including a campaign in 1961 against the policies of Rich’s Department Store.