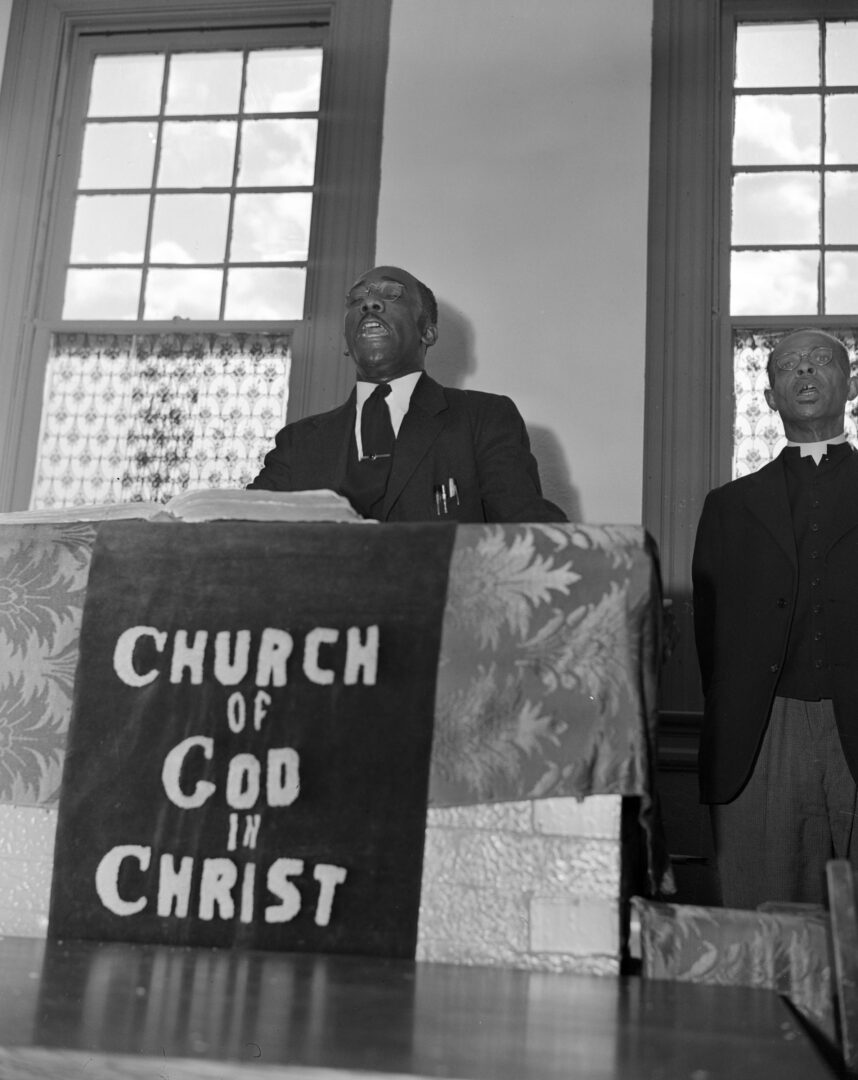

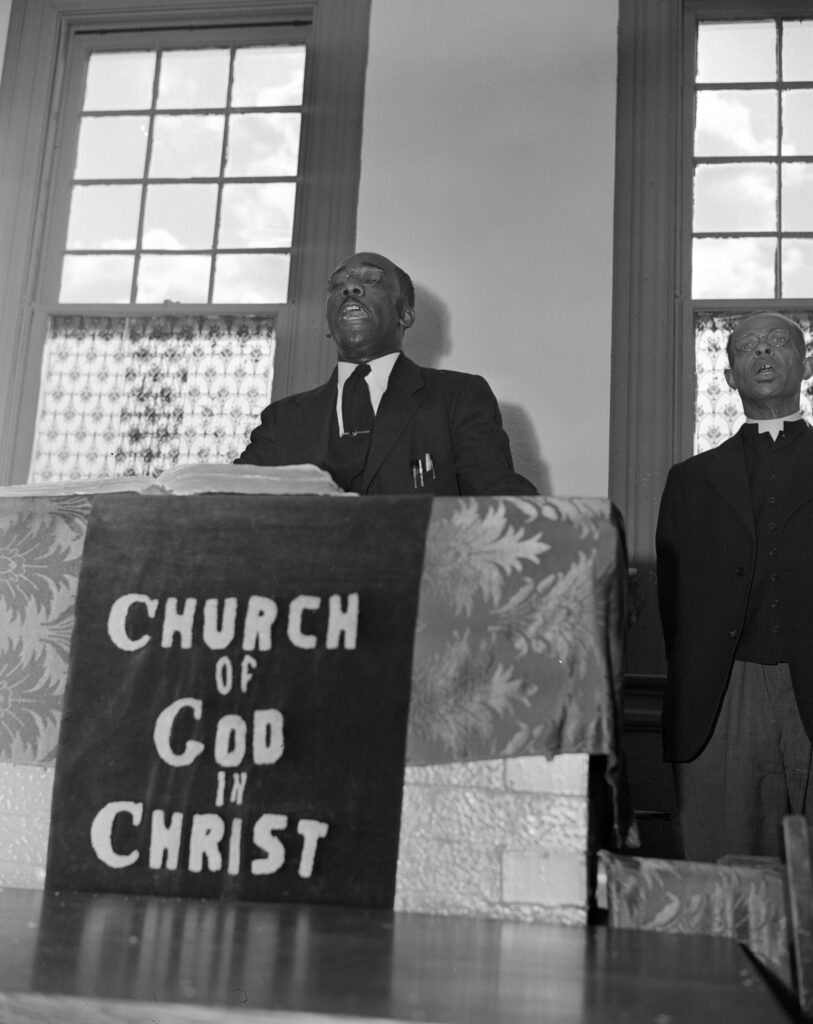

The Church of God in Christ (COGIC) is the largest Black Pentecostal denomination in the country. As of 2005 there were more than 100 COGIC churches around the state, with a total membership of more than 40,000.

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

COGIC’s origins date back to the tense race relations of the 1890s South, an era of widespread lynchings, heated disenfranchisement campaigns, the beginnings of legalized segregation, and the Populist revolt. During this volatile time, a small group of Black Baptist preachers in Mississippi began to preach of tangible contact with the divine (the Holy Spirit) that genuine believers could and should experience. They proclaimed that converted believers could experience a state of freedom from sin (“entire sanctification”) and that they could be miraculously healed of illnesses and sufferings. These teachings were hallmarks of the nineteenth-century Holiness movement, which spread especially among Baptists, Methodists, and Presbyterians. Other Black Baptists in Mississippi found these Holiness teachings heretical and expelled the ministers, who then reorganized themselves and their converts as the “Church of God in Christ.”

In 1907 Charles Harrison Mason, a founder and the head of COGIC until his death in 1961; Mack E. Jonas, state overseer for Georgia and Alabama, and later bishop of the Northwestern Jurisdiction of Ohio; and a few other ministers, doubting that they had fully experienced the power of the Spirit, traveled to a huge revival at Azusa Street in Los Angeles, California. There, amid a crowd of Blacks, whites, Asians, and Latinos, they heard the distinctive Pentecostal message that true believers should experience the Spirit by “speaking in tongues”—or talking in unknown languages during a state of religious ecstasy. (In the Bible, Jesus’ disciples experienced such phenomena on the Jewish festival day of Pentecost; contemporary believers invoke this precedent by calling themselves “Pentecostal.”) Mason and the others brought this Pentecostal message back to the South, where it spread quickly. Centered in the Tennessee-Arkansas-Mississippi area around Memphis, Tennessee, COGIC spread through the work of traveling preachers.

During its first twenty-five years, the denomination was interracial in principle and in practice. By the 1920s, COGIC had established twenty-one churches in Georgia, with the new converts likely seeking a more direct, experiential encounter with the divine than was given at the sermon-centered Baptist and Methodist churches from which they came. As was true of other Pentecostal groups, COGIC grew dramatically in the late 1960s and 1970s. By the 1980s, COGIC had more members nationwide than the Presbyterian Church USA and Presbyterian Church in America combined.

Common assessments that COGIC and other Pentecostal groups constitute a “reaction to modernity” or offer an “otherworldly refuge” for oppressed and suffering people overlook the social radicalism that COGIC has at times demonstrated, including its open pacifism during World War I (1917-18). In the midst of the 1968 sanitation workers’ strike in Memphis, Martin Luther King Jr. preached what was to be his last sermon at COGIC’s Mason Temple in that city. If anything, COGIC and other Pentecostals seek unmistakable contact with the divine in the here and now, not in the hereafter. They want, as the leading historian of Pentecostalism has called it, “heaven below,” which may explain the denomination’s growth in times of social flux and uncertainty.