Georgia’s population has changed remarkably since the 1970s, with new ethnic groups arriving from all over the world. These immigrants have brought with them a diversity of languages, religious practices, food and craft traditions, music, styles of dress and decoration, and ways of celebrating. During ethnic celebrations immigrants can display and enjoy many of their native cultural traditions while joining with others from their homelands.

Georgia’s Ethnic Groups

Centuries ago, Georgia’s native populations, which included Creek and Cherokee Indians and other Native American groups, were joined by settlers from Scotland, Ireland, England, Germany, and other European countries and by enslaved Africans from various groups in West Africa. Georgia also has had a substantial Jewish population since its settlement in 1733, when a shipload of Sephardic (Spanish and Portuguese) and Ashkenazic (German) Jews arrived in Savannah from England.

Contemporary Georgians of Native American ancestry, as well as African Americans, Scottish and Irish Americans, and other early European Americans, participate in celebrations of their ethnic histories. From the St. Patrick’s Day festivities in Savannah and Dublin to the Scottish Highland Games in Stone Mountain, ethnic celebrations of Georgia’s earliest groups continue to grow. While recent years have seen dramatic increases in the number and diversity of new immigrants, the Portuguese community along the coast, the Chinese communities of Augusta and Atlanta, and the Greek and Middle Eastern communities in Atlanta have been in place for generations.

In recent years the economic prosperity of Atlanta and the Sunbelt, along with successful refugee resettlement programs, have made Georgia a magnet for new settlers. Vietnamese, Cambodian, and Laotian refugees who began coming to Georgia in the mid-1970s have been followed by more-recent refugee populations, including Somalians, Ethiopians, Eritreans, Ukrainians, Russians, and Arabs.

When a group immigrates to a new country, its members find that they have to modify their way of life, including their celebrations of significant events. An event that may last for days in the homeland shortens to adjust to the American workweek and to the new physical and commercial environment. In China, Vietnam, and Korea, for example, the New Year celebration is a multiday event permeating entire towns and cities, but on American soil it becomes a smaller weekend event at a local community center. Generally, immigrants find ways to maintain the most essential elements of such events.

Types of Celebrations

Many ethnic celebrations are calendar events commemorating political holidays, religious holidays, or dates in the lives of such important figures as Mahatma Gandhi. Calendars followed by immigrant and ethnic groups include the Buddhist, Chinese, Eastern Orthodox, Hindu, Islamic, and Jewish calendars. In some cases immigrants move the original date of the holiday. The Caribbean community in Atlanta, for example, celebrates Carnival on Memorial Day weekend, in part because May is warmer than February.

New Year celebrations can occur at any time, depending upon the calendar followed. They take place at community centers, places of worship, or in people’s homes.

Independence Day marks a significant historical event—the day a country was founded or reclaimed. For those no longer living in their home country, Independence Day draws people from the same country together. Whatever their differences in background—because of region, group affiliation, or religion—Independence Day can be celebrated by all. Mexicans, Koreans, Pakistanis, Ghanaians, and many others groups celebrate their respective occasions. They usually fly the American flag alongside that of their homeland, and they often gather to celebrate American independence on July the Fourth as well.

As the Christian calendar commemorates the birth and resurrection of Christ, other religious calendars highlight figures and historical events. They also include periods of fasting—abstinence from food, usually accompanied by prayer and contemplation—that are preceded or followed by feasting and celebration. For instance, during the month of Ramadan, the ninth month of the Muslim calendar, Muslims fast throughout the day, breaking the fast only after sunset. Their Id-al-Fitr (Feast of Fast Breaking) celebration, which takes place at the end of the month, is a festive event with abundant foods and gifts for children.

Carnival—most familiarly known in the United States as the Mardi Gras celebration—is widespread throughout the Western world. The name carnival is from Latin, meaning to take meat away. Carnival is celebrated before Lent, which is the period of fasting (generally, abstaining from consumption of meat) that lasts for forty days preceding Easter, and which is commonly observed by Roman Catholics and some Protestants. In Georgia, Carnival celebrations are held by Brazilians, Cajuns, Caribbean immigrants, Germans, and others. Revelry and costuming are commonly found in Carnival celebrations.

Some ethnic events relate to life cycle events like birth or naming ceremonies, coming of age, weddings, and funerals. These occasions also offer a time for people of the same ethnicity to share traditional foods, wear traditional dress, and enjoy customs that connect them with their homelands and with one another.

Ethnic Festivals

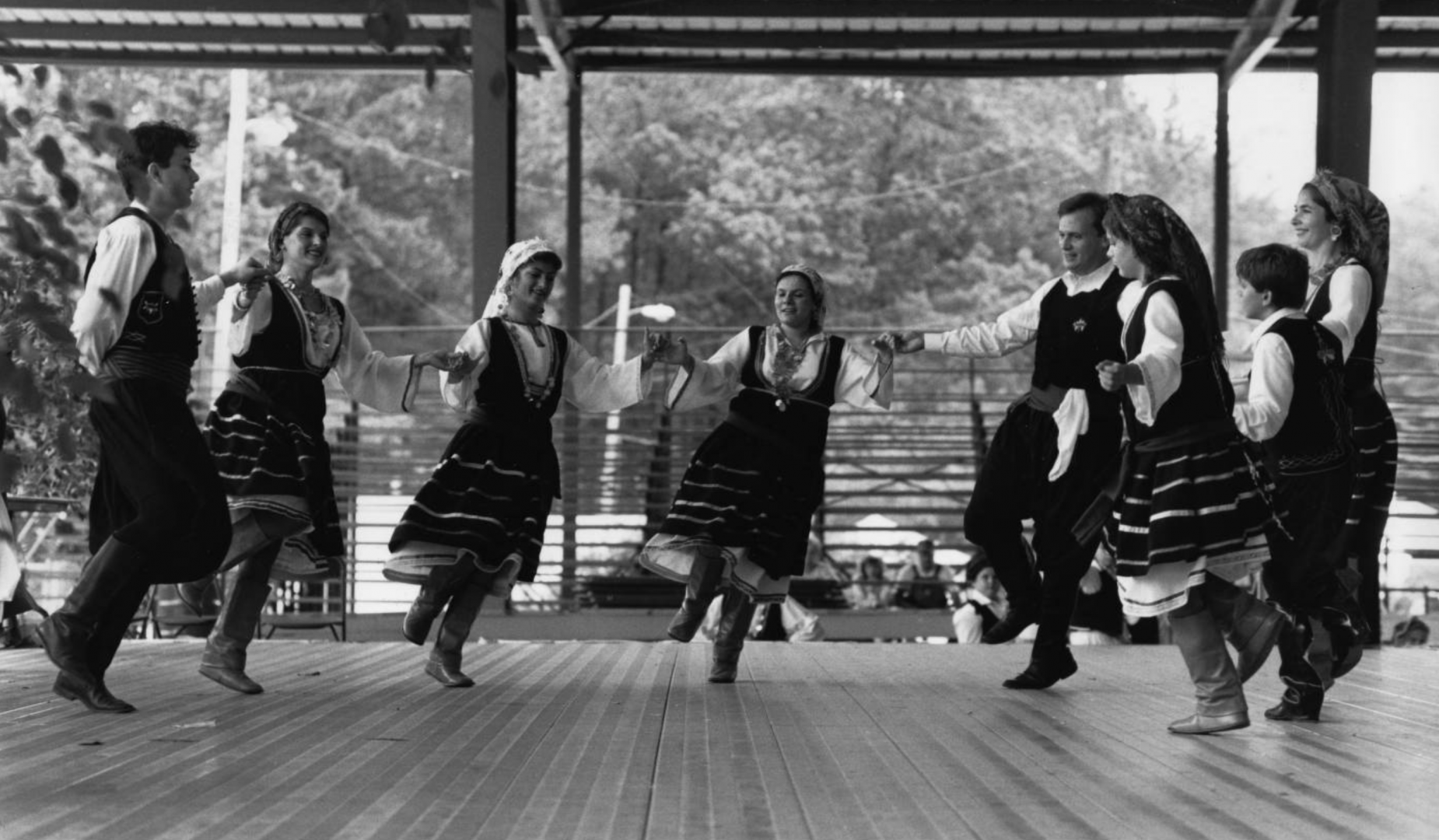

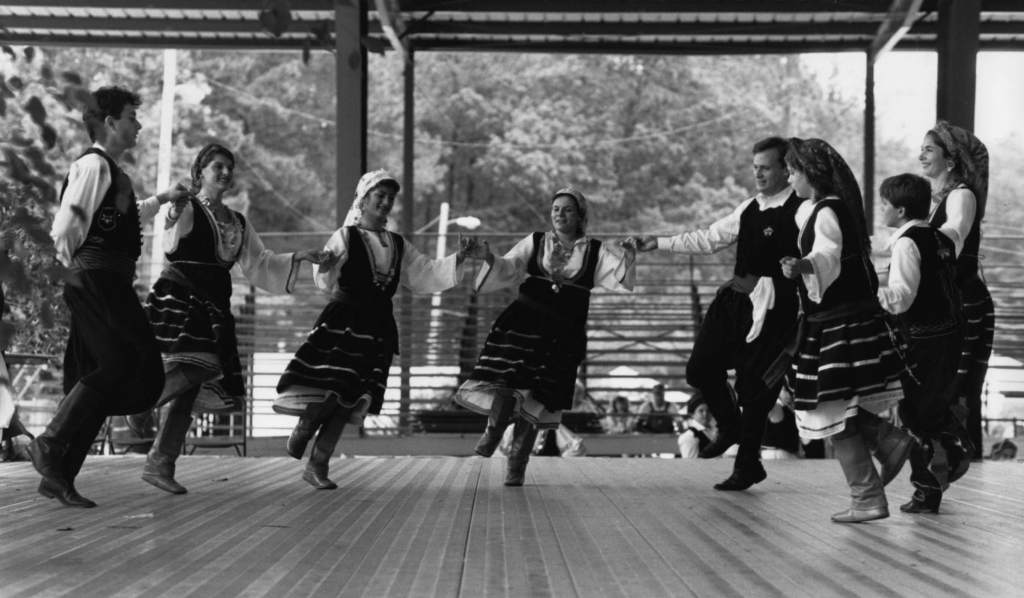

Not all ethnic celebrations relate to annual calendars or to life cycle events; they may celebrate a community’s background, his tory, and culture and offer samplings of ethnic traditions—food, dance, music, and other arts. These festivals are growing in number and popularity and include the Greek Festival, the Middle Eastern Festival, the Scottish Highland Games, and the Hispanic Festival in Atlanta and the Pan African Festival in Macon.

Many celebrations are attended only by community members. They may be small, involving members of a single family, or quite large, involving hundreds of people sharing the same ethnic background. These can be termed “in-group” celebrations. Other celebrations include noncommunity members and serve as “outreach” events. The Greek Festival is such a celebration. Generally, outreach celebrations are well advertised through local media. In-group celebrations may not be as easy to find but are often open to the general public.