The parks, parkways, and residential landscapes of Atlanta, Columbus, and several other Georgia places have been influenced by the work of Frederick Law Olmsted. Olmsted is considered to be the father of landscape design, a profession he helped to define over the latter half of the nineteenth century through his works and writings. His work in Atlanta during the 1890s was continued into the twentieth century in several other Georgia cities by Olmsted Brothers, a firm created by his sons and successors.

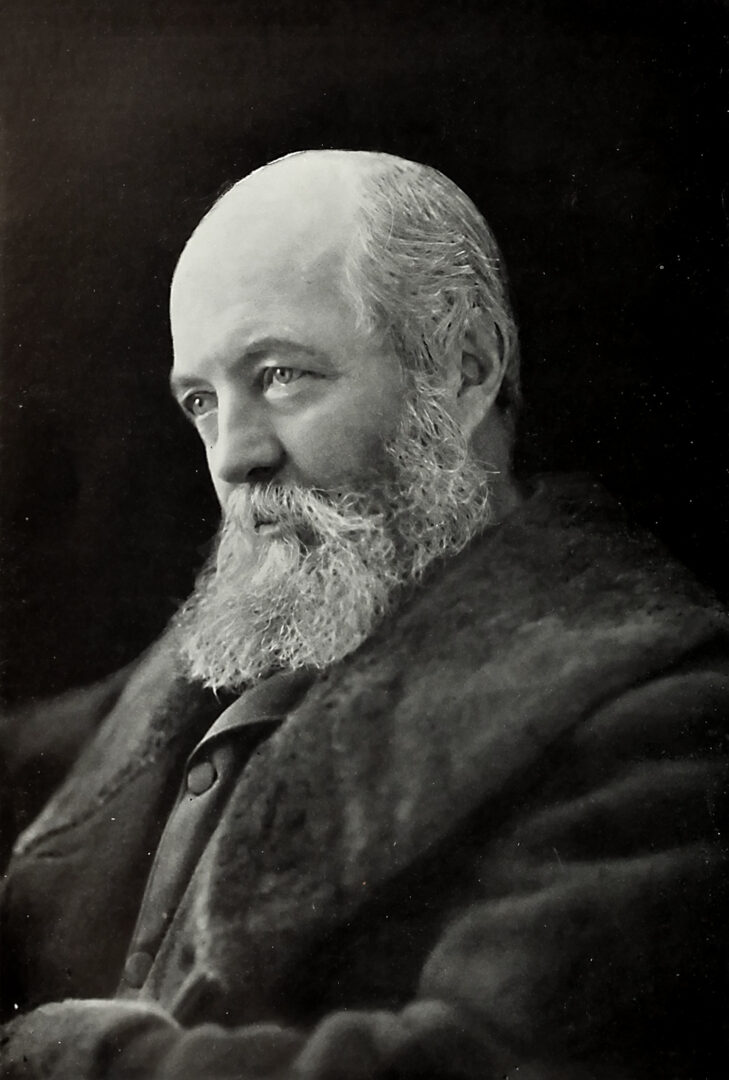

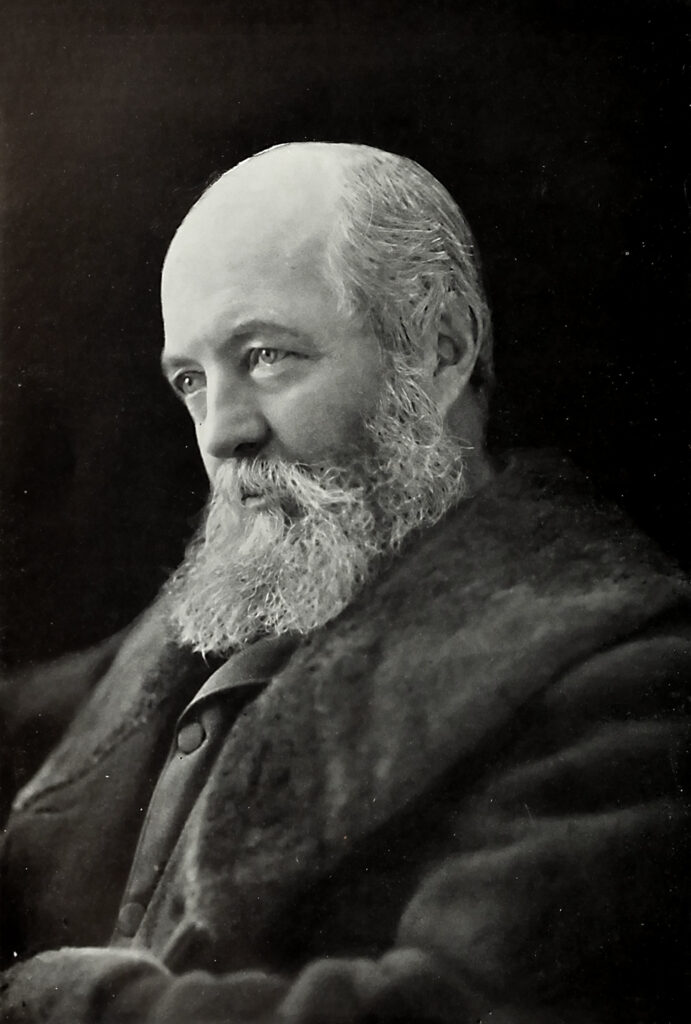

Image from James Notman

Olmsted’s long and varied career resulted in such seminal landscape-design projects as Central Park in New York City; one of the first residential planned communities, in Riverside, Illinois; the “Emerald Necklace” in Boston, Massachusetts; the Capitol grounds in Washington, D.C.; and the Biltmore estate in Asheville, North Carolina. Through the work of his stepson, John Charles Olmsted (1852-1920), and his son, Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. (1870-1957), Olmsted’s firm survived for almost a century and led the way in every aspect of landscape architectural design.

Though a New Englander by birth, Olmsted traveled extensively and spent an early part of his career—including two years (1852-54) in the South—as a prolific and influential travel writer. The resulting publications and long letters earned him a reputation as an astute observer and social critic.

Having crossed Georgia twice during his 1850s sojourn, Olmsted was not a stranger to the state when he arrived in Atlanta to consult with the Cotton States Exposition commission in 1890. The well-known journalist Henry Grady and land developers, such as Joel Hurt, were largely defining the postbellum “New South,” and Olmsted’s national reputation as the chief landscape architect of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Illinois, made him the logical choice to advise the commission on their plans. Although his firm was not selected for the project, Olmsted made a valuable connection in Hurt, who shared many of Olmsted’s sensibilities and was just completing Atlanta’s first planned residential suburb, Inman Park, which was modeled on the earlier Olmsted and Calvert Vaux effort in Illinois. Encouraged by a mutual friend, Hurt commissioned Olmsted to draw up plans for a much larger suburban development, Druid Hills, and Olmsted returned in 1893 to present the preliminary design.

Courtesy of National Park Service, Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site

Olmsted’s design for Druid Hills is Georgia’s most complete and masterful example of his artistic principles, which were employed by others in a number of Atlanta developments, including Ansley Park, Peachtree Battle, and Garden Hills. After the retirement of the man called the “prophet of the suburbs,” his sons continued to consult on Druid Hills as well as on Atlanta’s Piedmont Park and Grant Park. Druid Hills, with its string of parks along parkways and spacious residential lots along curving and tree-lined streets, displays the Olmsted firm’s design principles. These principles influenced the landscape not only in Atlanta but also in Columbus, Savannah, and other Georgia sites, including the Augusta National Golf Club, which hosts the annual Masters Tournament, and residential areas in Rome and Cartersville. In Savannah, Olmsted Associates worked on parks and subdivisions.

Courtesy of Historic Preservation Division, Georgia Department of Community Affairs.

Columbus, from 1920 to 1937, became the only hub of the Olmsteds’ work outside of Atlanta. W. C. Bradley, president of Eagle and Phenix Mills, asked W. B. Marquis of the Olmsted firm to continue landscape work begun when he was in the employ of Augusta’s P. J. Berckmans (of Berckmans Nursery). The Bradley residence, also known as Sunset Terrace, became the largest residential commission of the Olmsted firm in Georgia and was described as an important modern garden in The Garden History of Georgia, 1733-1933. Later, the Bradley family subdivided the estate, and today a good portion of the ravine, an Olmstedian signature landscape, remains on the grounds of the Columbus Museum.