Over the years Georgians have made significant contributions to the creation and survival of southern gospel music. Georgians have been in the forefront among the composers, publishers, and performers of music characterized by close harmonies and a strong religious lyrical content. Southern gospel music, whose performers and audiences are primarily white, is to be distinguished from the popular sacred music of African Americans, which is usually referred to as Black gospel music, or simply as gospel music.

Shape-Note Singing and Songbooks

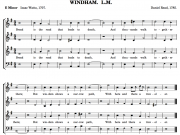

The innovation in music that led directly to the emergence of the southern gospel trend was the introduction around 1800 of shape-note musical notation. The motivation behind the shape-note system was the belief on the part of music instructors that the use of distinctive shapes to identify the musical notes fa, sol, la, and mi would make it easier for singers to sight-read, thereby improving the quality of their singing. The first system that achieved a significant following consisted of four shapes. It has survived as a defining characteristic of Sacred Harp singing, sometimes referred to as “fasola” singing. Inspired by European musical practices, some American musicians wanted to adopt a seven-shape system. In 1846 Jesse B. Aikin of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, published his Christian Minstrel, a songbook employing a seven-shape system, and many rural singers began following the new system.

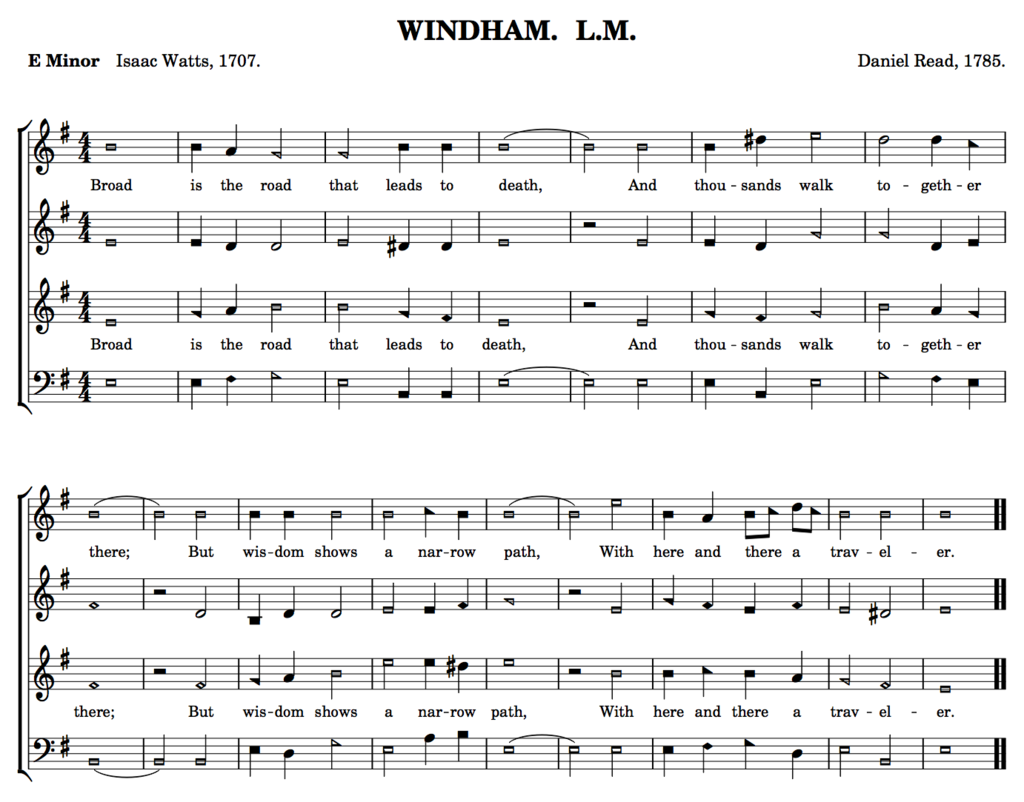

The tune "Windham" as it appears in The Sacred Harp, 1911 edition. Image from Wikimedia.

A driving force behind the seven-shape system among rural singers arose during the 1870s in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley. There, the seven-shape advocates Ephraim Ruebush and Aldine Kieffer established a songbook publishing house, inaugurated a musical periodical championing rural music and the seven-shape note system, and opened the Virginia Normal Music School, the country’s first educational facility devoted to the teaching of the seven-shape music system.

With the Ruebush-Kieffer conglomerate as a model, publishing companies, musical periodicals, and normal schools that were dedicated to the furtherance of seven-shape note singing sprang up throughout the South. The most influential publishers in Georgia were J. M. Henson in Atlanta and A. J. Showalter in Dalton. The last of these to cease publication was Henson, who retired from the business in 1967.

Typically, seven-shape songbook publishers placed on the market one or two books per year. It has been estimated that by 1930 some 200,000 of these songbooks were sold each year in the rural South. To enhance sales, publishers included in each new book several previously unpublished songs. Consequently there was a demand for songwriters. Many of Georgia’s early southern gospel singers were also composers of songs set to the seven-shape notational system and popularized by their fellow singers. These composers included J. W. Askew, Roswell G. Clark, H. C. Collins, J. M. Henson, Andrew Jenkins, Charles E. Moody, J. L. Moore, James Cleveland Moore, Homer F. Morris, A. J. Showalter, J. L. Sisk, Charlie D. Tillman, and McD. Weams.

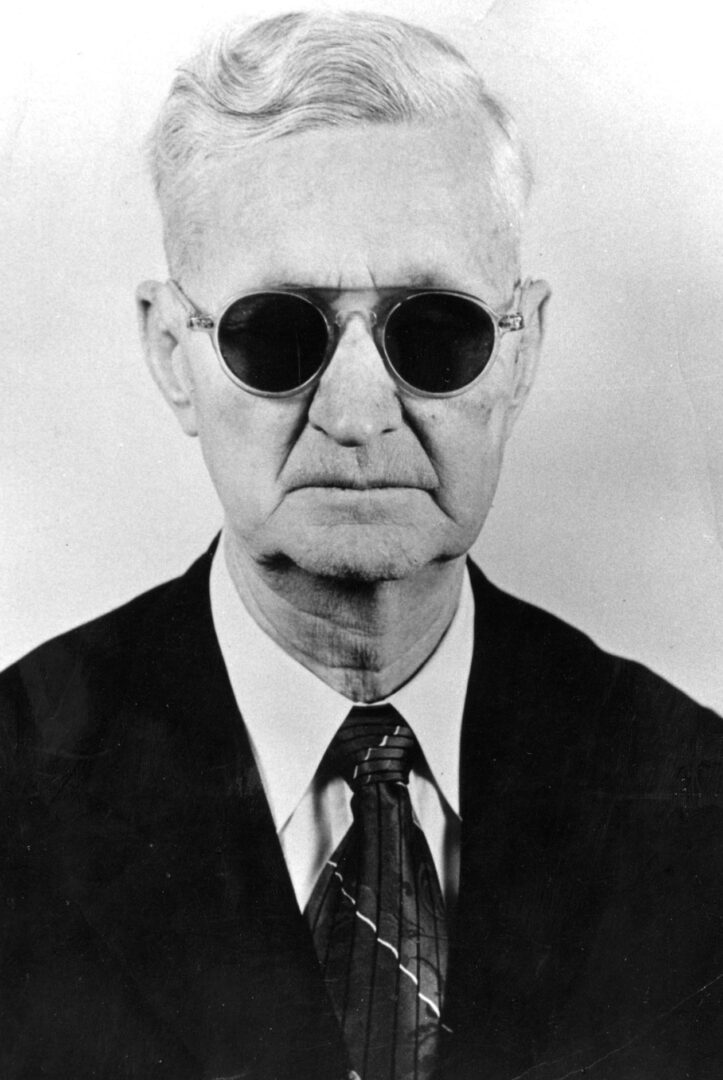

Courtesy of Mary Lee Eskew Bowen

Publishers also promoted their songbooks by organizing quartets who traveled around the South, singing the publisher’s songs and selling the songbooks in which the songs appeared. Many Georgians are still writing songs for the songbooks that are used at present-day singing conventions, but they have to look to other states for a publisher.

Singing Schools and Conventions

Although seven-shape songbooks found wide use in southern rural churches, their widest distribution was among singers and attendees at singing conventions. These audience-participatory events were organized at community, regional, and eventually state levels. They took place at periodic intervals, from monthly to annually. In the days before movies, radio, and television, singing conventions were heavily attended.

Community singing schools provided a constant supply of competent singers and persons capable of leading congregational singing. Usually held in the summer months and typically lasting for two weeks, these singing schools were conducted by graduates of similar schools or one of the several southern normal schools. The instructors traveled from community to community, holding classes in schools and churches and boarding with local residents during their stay. They taught music theory, sight-reading, conducting, and harmony.

The Persistence of Southern Gospel Music

Southern gospel music makers flocked to recording, radio, and television studios. The success of the early southern gospel quartets inspired the formation of musical groups of other sizes—duets, trios, and larger ensembles.

In time, what would be called southern gospel music asserted its influence on other musical genres popular in the South. Early country music acts incorporated into their repertoires that brand of gospel music available from seven-shape note sources. When bluegrass music emerged as a recognized genre in the late 1940s, the southern gospel style of singing was among the country music elements from which bluegrass borrowed.

Among early Georgia-based professional singers whose repertoires included southern gospel–inspired material were the Reverend Andrew Jenkins Family (Atlanta), Smith’s Sacred Singers (headed by J. Frank Smith of Jackson County), several recording groups (Calhoun Sacred Quartet, Turkey Mountain Singers, Moody Quartet, Gordon County Quartet) that included composer Charles E. Moody, and numerous Atlanta-based groups, such as the Harmoneers, the Blue Sky Boys, James and Martha Carson, the Sunshine Boys, the Swanee River Boys, Homeland Harmony Quartet, Hovie Lister and the Statesmen, the LeFevr

Groups that owe a debt to the seven-shape notational system are still performing in Georgia. The Lewis Family of Lincolnton, known as the “First Family of Bluegrass Gospel Music,” blends a southern gospel–derived vocal style with a string band accompaniment that has roots in old-time country music. Another bluegrass band, IIIrd Tyme Out of Suwanee, records southern gospel material in the close-harmony male-quartet style. Other Georgia-based artists include Little Jan Buckner (Clarksdale), Jeff and Sheri Easter (Lincolnton), the Encouragers (Savannah), Brian Free (Douglasville), Jake Hess (Columbus), the Marksmen (Murrayville), Naomi and the Segos (Centerville), the Nelons (Smyrna), Peach State Quartet (Alpharetta), Randy Perry (Dahlonega), and Poet Voices (Ringgold).