George T. Heery was a prominent figure among a family of Georgia architects. Heery’s father practiced in Athens for several decades beginning in the late 1920s, and two of his children later entered the field as well, working alongside their father as co-founders of the Brookwood Group.

George Thomas Heery was born in Athens on June 18, 1927. His father, C. Wilmer Heery, graduated from the architecture school at the Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta in 1926, with a class that also included Marshall Oliver Saggus, Marthame Sanders, and Sanford Ayers, all of whom would go on to have distinguished careers in architecture. Harold Bush-Brown, then in his second year as head of architecture, was continuing the Beaux-Arts curriculum that Francis Palmer Smith established in 1909. Thus, Wilmer Heery was well grounded in the classical tradition, in history as a source for principles and form, and in what Beaux-Arts advocates referred to as the “art” of building. In the mid-1940s George Heery followed in his father’s footsteps and became a student in Georgia Tech’s architecture school.

The post–World War II (1941-45) Georgia Tech faculty, however, differed markedly from the faculty who had taught Wilmer Heery in the early 1920s. George Heery’s mentors were increasingly moving toward the functionalist modern approach to design, which was based on Bauhaus traditions. The faculty included Paul M. Heffernan, Julian Harris, Sam Hurst, and visiting design critics Cecil Alexander, Herb Millkey, H. Griffith Edwards, and Richard Pretz. The firm of Bush-Brown, Gailey, and Heffernan, of which all the partners were senior faculty as well as practicing architects, was at that time designing pioneering functionalist college buildings for Georgia Tech. Educated by this polyglot assemblage of instructors with Beaux-Arts training and modernist leanings, Heery graduated in 1951 and stayed on at Georgia Tech the following year to teach.

Heery and Heery

Upon his graduation, Heery proposed to form a partnership with his father, with Wilmer continuing to practice in Athens and George heading a new Atlanta office of Heery and Heery. Heery built for himself a modern house (1951-52) in Atlanta, on property adjacent to Finch and Barnes’s Golfview Road cul de sac (1951-54), which was full of early modern houses. In Atlanta, where residents at every social level were still building traditionally styled houses, the home was a symbolic gesture through which Heery aligned himself with other emerging modernists, including Finch, Alexander, Barnes, and Rothschild of FABRAP; Stevens and Wilkinson; and John Portman. Thomas Ventulett, Jerome Cooper, and Joe Amisano would soon join this first generation of modern architects in Georgia. These firms (especially Heery and Heery) in turn apprenticed, mentored, and encouraged those who would form the second generation of modern designers in Georgia, notably Mack Scogin, Merrill Elam, and Larry Lord.

In 1961 Heery began to develop advanced project-management procedures for controlling time and cost through pre-design, design, and construction. His ideas immediately informed the successful fast-track design and construction of Atlanta Stadium (later Atlanta–Fulton County Stadium; 1963-65, razed 1997),a joint venture with FABRAP that served as the catalyst for Heery’s reputation as a specialist in sports facilities. In 1975 Heery’s publication of Time, Cost, and Architecture led many to conclude that Heery literally “wrote the book” on construction management. His ideas evolved to embrace real estate and “strategic facilities planning” as well as “bridging,” a method designed to reduce risks, costs, and post-construction problems for owners. By the mid-1990s Heery focused his methods on college, university, and nonprofit development management.

Heery also continued to reshape and expand his architecture firm. In 1966 he formed Heery Associates to spearhead construction program management and around that time established Heery Interiors. By 1969 Heery Graphics emerged, and an early 1970s merger with the mechanical, electrical, and structural engineering firm of J. W. Austin was followed, by decade’s end, with the creation of Heery Energy Consultants. Civil engineering and landscape architecture were the focus of Heery Engineering and Land Planning, established in 1982. The Heery interests were sold to a British group in 1986 and reorganized as Heery Architects and Engineers, Heery Engineering, and Heery Program Management. Two years later Heery left the organization and was succeeded as chief executive officer by James Moynihan. The company was later reorganized as Heery International and participated in such notable Atlanta ventures as Monarch Tower (1995-97), Turner Field (later Center Parc Stadium; 1996-97), and the Georgia Aquarium (2003-5).

In 1989, Heery, along with his daughter, Laura, and son, Shepherd, founded the Brookwood Group, a real estate development, planning, and management consulting firm.

Notable Projects

Heery’s offices, in the early years, were housed in a Miesian black-steel-and-glass office building that his firm designed and constructed in 1971 at 880 West Peachtree Street. Projects in the early 1970s showed an interest in straightforward construction materials, including Brutalist concrete delineated in carefully proportioned elevations at Stouffer’s Atlanta Inn (1969-72). The Martin Luther King Jr. Middle School (1969-73) in Atlanta was an early attempt at nonstructured classrooms during the 1960s, but it was also an inward-oriented building whose exterior presented a Brutal graffiti-proofed fortress against the social unrest of the period. The Woodruff Health Sciences Center (1973-76) at Emory University, designed by Merrill Elam, reflected the Brutalist school’s materialist interest in raw concrete, monumental scale, and an “as found” straightforwardness. Heery Architects and Engineers’ Georgia Power Company corporate headquarters (1976-81) in Atlanta, for which Mack Scogin served as project architect, is a black-steel-and-glass structure edging the expressway, its southern flank dramatically sliced with the angle of the sun in mind to maximize energy benefit.

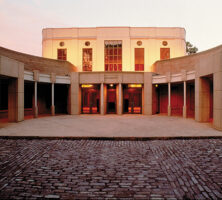

After collaborating with FABRAP on the Five Points MARTA station, Heery began to take over the principal design role for the Coca-Cola Company, whose earlier buildings FABRAP had built in three phases (1970, 1980, 1981) but whose Central Reception Building (1984-86) and Coca-Cola U.S.A. Building (1987) are by Heery. He also collaborated with Rosser Fabrap International on the Georgia Dome (1989-92).

When 999 Peachtree at Peachtree Place was completed in 1987, Heery put on display his never entirely abandoned classic point of view, utilizing travertine marble veneer for the twenty-eight-story skyscraper. The building is set off with a piazza and presents a balanced, orderly facade with good proportions and well-observed scale. Heery was also associated with the construction of Philip Johnson’s IBM Tower (or One Atlantic Center; 1985-87) in Midtown Atlanta. Institutional buildings of note are the Atlanta History Museum (1990-93) at the Atlanta History Center and the Dorothy Chapman Fuqua Conservatory of the Atlanta Botanical Gardens. Heery also built the Callaway Student Athletic Complex, named for Fuller E. Callaway III, at Georgia Tech (1975-77, with FABRAP), and the Student Recreation Center at Georgia State University (2001).

In the mid-1990s, after retiring from the Heery conglomerate, Heery developed the Wakefield, returning full circle to his classical sensibilities. The high quality and luxurious character of this high-rise apartment cooperative make it “a classic,” not only because of its inherent taste, refinement, and elegance but also because it served as a model and trendsetter for Buckhead, that bastion of Atlanta’s old-world standards of style and beauty.

Heery played an active role at the Brookwood Group well into his eighties and only stepped down as chairman in 2013. He was a Fellow of the American Institute of Architects and a member of the Royal Institute of British Architects.

Heery died in Atlanta, on January 21, 2021, at the age of ninety-three.