Since the late nineteenth century, the tradition of gathering together at singing conventions to “make a joyful noise unto the Lord” has been an important part of the social and cultural life of many Georgians. The vocal and instrumental renditions heard at these conventions, first referred to as gospel music, is now known as southern gospel music.

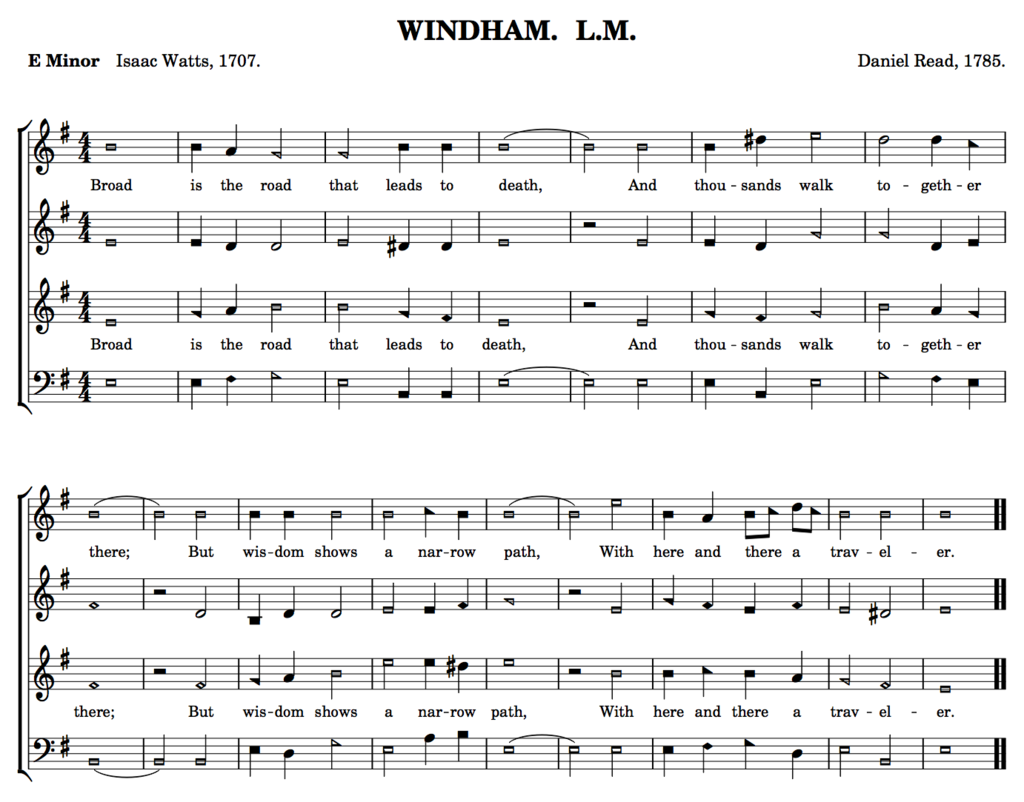

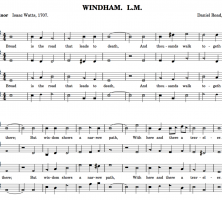

The songs that are sung at these conventions appear in printed form set to a written musical system called seven-shape notation. This system, invented to make it easier to read music, was an early competitor of the four-shape notational system known as Sacred Harp. Because of its immense popularity in the South, the seven-shape notational system became a defining characteristic of southern gospel music. The shapes employed in the seven-shape notational system are as follows: equilateral triangle = do, semicircle = re, diamond = mi, right triangle = fa, oval = sol, rectangle = la, and quarter circle = ti. Southern gospel singing is also characterized by instrumental accompaniment and differs in that respect from Sacred Harp singing, which is performed a capella.

The music heard at singing conventions is published in paperback books called convention books, and several new ones, containing new gospel songs, appear annually. A gospel song, according to A Dictionary of Protestant Church Music, is “a simple harmonized tune in popular style combined with a religious text of an emotional and personal character in which, rather than God, the individual (and/or the individual religious experience) is usually the center. The text, primarily concerned with the conversion experience, life after death and personal companionship with Jesus, is usually subjective in nature, developing a single thought instead of a line of thought. . . . The melodic, harmonic and rhythmic style is often associated with the style of secular music, often drawing attention to itself and away from the text.” The practitioners of southern gospel music are predominantly Anglo-American Protestants, and their music is to be distinguished from the gospel music tradition embraced by African Americans known as Black gospel music or often simply as gospel music.

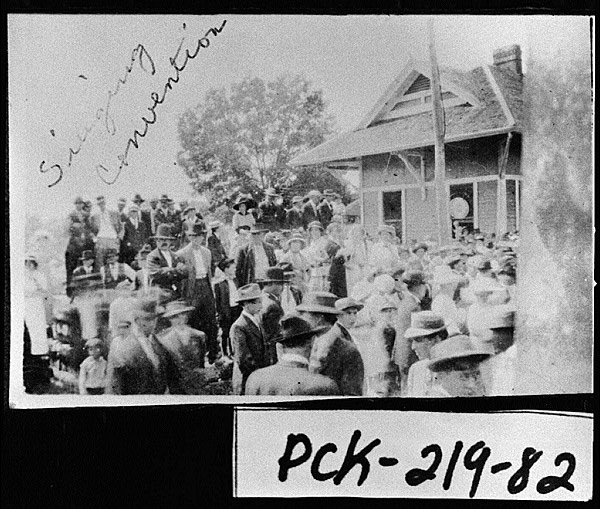

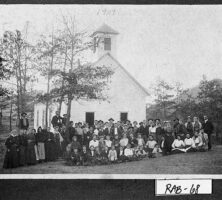

The first documented singing convention in Georgia was the South Georgia Singing Convention, founded by William Jackson Royal in 1875 in Irwin County. The success of this endeavor soon gave rise around the state to numerous other local singing conventions, which were usually organized as regularly occurring countywide events. Jasper, the seat of Pickens County, for example, hosted a biannual convention that attracted hundreds of participants during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

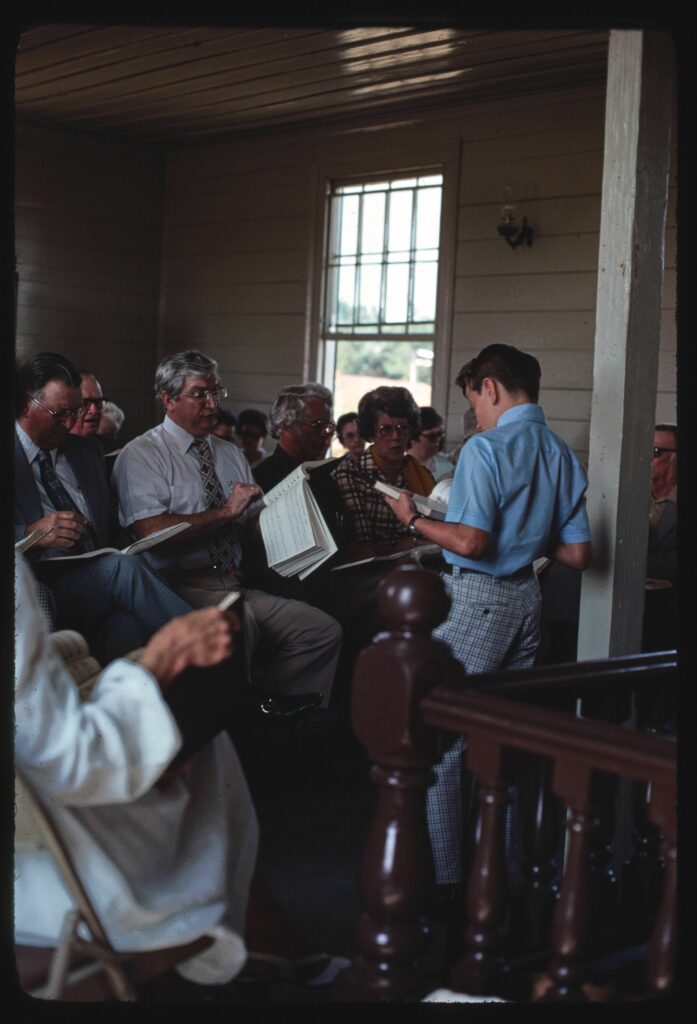

Singing conventions are audience-participation affairs, but they are organized in such a way that those with the talent and desire are allowed to take their turn leading the congregational singing. The annual supply of new songs provides the means for honing sight-reading skills.

In the days before television and the proliferation of motion picture theaters, local singing conventions provided opportunities not only for singing but also for socializing. The ultimate social experience to grow out of the singing conventions was the all-day singing with dinner on the grounds, a long-lived southern tradition especially popular in rural areas. With the coming of the automobile, singing conventions were no longer restricted by transportation limitations to local areas. In 1927 the first statewide singing convention held in Georgia led to an annual event that continues to the present time. The annual national singing convention, first held in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1937, allows Georgia singers to socialize and harmonize with singers from other parts of the country.

Contributing to the success of the singing conventions are the gospel music composers and publishers, many of whom called Georgia home. Best known among Georgia publishers of seven-shape-note songbooks were J. M. Henson of Atlanta and A. J. Showalter of Dalton. Currently the publishers of the songbooks used at the Georgia singing conventions are located in other states. Georgia composers whose songs became early standards of southern gospel music include J. M. Henson (“Watching You”), Andrew Jenkins (“God Put a Rainbow in the Cloud”), Charles E. Moody (“Kneel at the Cross”), A. J. Showalter (“Leaning on the Everlasting Arms”), and Charlie D. Tillman (“Life’s Railway to Heaven”). Compositions by many of Georgia’s gospel music singers, active during the latter part of the twentieth and early part of the twenty-first century, appear regularly in the annual output of convention songbooks. Among these songwriters are K. Wayne Guffey, Hansel Hunter, Mildred Johnson, Cheryl Truelove Pass, Eloise Phillips, Byron Pollard, and Fred Rich.

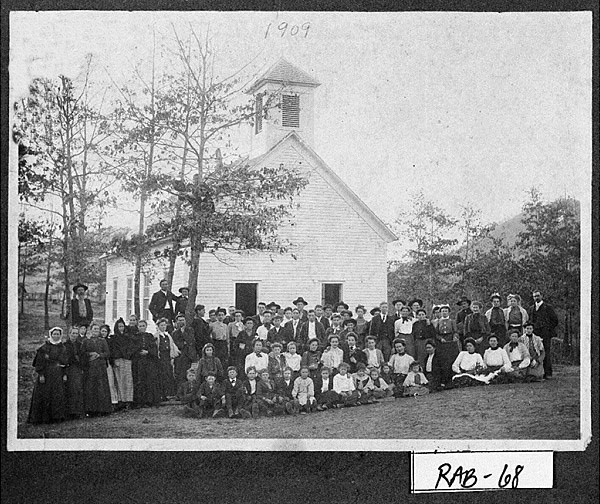

In the early years of the seven-shape-note singing tradition, sight-reading and other aspects of music were learned at singing schools. Held mainly in rural churches and schoolhouses, the singing schools were conducted by itinerant teachers who had learned their craft at similar schools and perfected their skills at many an all-day singing. These singing-school teachers traveled from community to community and boarded with local residents while conducting their schools, which lasted from two to four weeks. End-of-school community singings, where students demonstrated their newly acquired musical abilities, served as stepping stones to the local singing conventions that were later organized.

Community-based singing schools have all but disappeared from the scene. In Georgia their function has been assumed by the North Georgia School of Gospel Music, which conducts classes each summer. The curriculum includes music theory, harmony, sight-reading, ear training, conducting, composition, piano, and voice.

There are fewer local singing conventions in the twenty-first century than in the past, but statewide and county gatherings still attract several hundred Georgians annually.