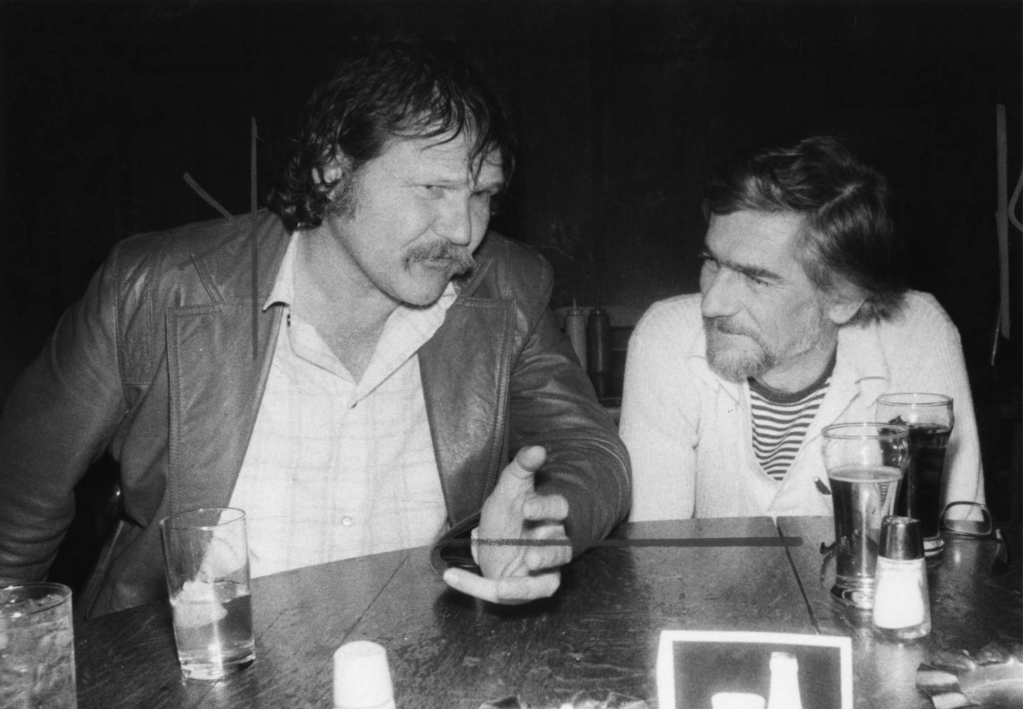

Harry Crews was a prolific novelist whose often freakish characters populate a strange, violent, and darkly humorous South. He was also the author of a widely lauded memoir, A Childhood: The Biography of a Place, about growing up poor in rural south Georgia. Crews focused much of his work on the poor white South, influencing a growing number of younger writers to do the same, including Larry Brown and Tim McLaurin.

Early Life

Harry Eugene Crews was born in Bacon County on June 7, 1935, the second of two sons. His parents, Myrtice and Ray Crews, were poor tenant farmers barely scratching out a living. After his father died of a heart attack in the middle of the night with Crews, just twenty-two months old, asleep beside him, Myrtice soon married Ray’s brother Pascal. Her decision would prove fateful, as Pascal revealed himself to be a violent and dangerous drunk. In his memoir Crews describes the tenuous situation of his early family life: “The world that circumscribed the people I come from had so little margin for error, for bad luck, that when something went wrong, it almost always brought something else down with it. It was a world in which survival depended on raw courage, a courage born out of desperation and sustained by a lack of alternatives.”

Raw courage was needed early, as Crews experienced two major physical setbacks as a child. At the age of five, he was struck with a fever followed by leg cramps so severe that his heels drew up to the backs of his thighs. He was bedridden for more than six weeks before he could be carried around the farm. He then gradually began to walk again by hauling himself along a fence. Later in life Crews would blame psychological stress from his increasingly volatile home life as the cause.

When he was six, an accident during a children’s game called “pop-the-whip” caused him to be thrown into a cast-iron boiler being used to scald pigs. With burns covering more than two-thirds of his body, Crews survived, doctors told him, only because his head had stayed above water. He describes the ordeal in his memoir: “Then hands were on me, taking off my clothes, and the pain turned into something words cannot touch, or at least my words cannot touch. There is no way for me to talk about it because when my shirt was taken off, my back came off with it. When my overalls were pulled down, my cooked and glowing skin came down.”

Crews joined the marines when he was seventeen, while his brother was away fighting in the Korean War (1950-53). During his time in the service, Crews began to read seriously. When his term ended, he enrolled at the University of Florida on the G.I. Bill, with the intention of becoming a writer. The Agrarian writer Andrew Lytle, who had once taught Flannery O’Connor and James Dickey, was Crews’s undergraduate writing teacher.

Novels

The years leading up to his first publication were hard both personally and professionally. Crews married in 1960 and had two sons, but the marriage did not last. In 1964 tragedy struck when his older son drowned. Crews began teaching in 1962, and after years of rejection his first novel, The Gospel Singer, was published in 1968 and garnered good reviews. Its publication earned Crews a new teaching job at the University of Florida and paved the way for the publication of seven more novels over the next eight years, including Naked in Garden Hills (1969); Car (1972); The Hawk Is Dying (1973), which was adapted into a film released in 2006; The Gypsy’s Curse (1974); and the widely acclaimed A Feast of Snakes (1976).

Crews’s reputation as a bold and daring new voice in southern writing grew during this time. The well-known writer Norman Mailer said, “Harry Crews has a talent all his own. He begins where James Dickey left off.” His writing is rooted in the Southern Gothic tradition, but Crews has claimed other influences, notably the British novelist Graham Greene. Most of his books are set in modern-day Florida or Georgia and are often edgy in their exploration of such extremities as blood sports, the limits of sanity, and bizarre compulsions and obsessions.

Crews, like Flannery O’Connor, has an affinity for the grotesque in his characters. He explains this fascination as being rooted in a specific childhood experience—waking up in a carnival trailer one morning, Crews witnessed a bearded lady and a man with a cleft face talking about their dinner plans and kissing. Crews claims, “And I, lying at the back of the trailer, was never the same again.”

Nonfiction and Other Work

After 1976 Crews didn’t publish another novel for roughly ten years. During this time his persona would increasingly become a source of interest to critics and readers. He was frank in interviews about his drinking and drug use and often changed his appearance by wearing a Mohawk, shaving his head, or getting tattoos. One tattoo features a skull under which is written, “How do you like your blue-eyed boy, Mr. Death?” (The quote is from an untitled poem by E. E. Cummings.)

Crews continued to teach during these years, and he wrote screenplays, plays, and nonfiction pieces, some of which are collected in Florida Frenzy (1982). He also became a regular contributor to Esquire, Playboy, Sport, and other magazines. A column he wrote for Esquire called “Grits” laid the groundwork for what many critics consider his best book, A Childhood: The Biography of a Place (1978). In A Childhood Crews’s style is honest and unflinching as he describes the violence and desperation surrounding him as a young boy, yet he is also nonjudgmental and shows an affection and respect for people despite their flaws. This poignant account of life in rural Georgia among the very poor earned Crews wide praise from critics. The New York Times Book Review said of the work, “It’s easy to despise poor folks. A Childhood makes it more difficult. It raises almost to a level of heroism these people who seem of a different century…. A Childhood is not about a forgotten America; it is about a part of America that has rarely, except in books like this, been properly discovered.”

Late Career

Crews resumed publishing novels with All We Need of Hell (1987) and went on to publish The Knockout Artist (1988), Body (1990), Scar Lover (1992), The Mulching of America (1995), Celebration (1998), and An American Family: The Baby with the Curious Markings (2006). In 1997 he retired from his teaching career and continued to write. Published in France, Italy, Holland, Israel, and the United Kingdom, Crews was inducted into the Georgia Writers Hall of Fame in 2001. He is featured in the documentary Searching for the Wrong-Eyed Jesus (2005), which chronicles the road trip of a country musician through the South.

His papers are housed at the Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library at the University of Georgia in Athens.

Crews lived in Gainesville, Florida, until his death on March 28, 2012.