I Am a Fugitive from a Georgia Chain Gang! was a sensational best-selling book by Robert Elliott Burns. Published in 1932, it recounts the dramatic story of the author’s imprisonment in Georgia and his two successful escapes, eight years apart, with seven years of freedom, business success, and emotional intrigue in between. It was also the basis of a popular movie entitled I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang, produced later that year by Warner Brothers.

The Book

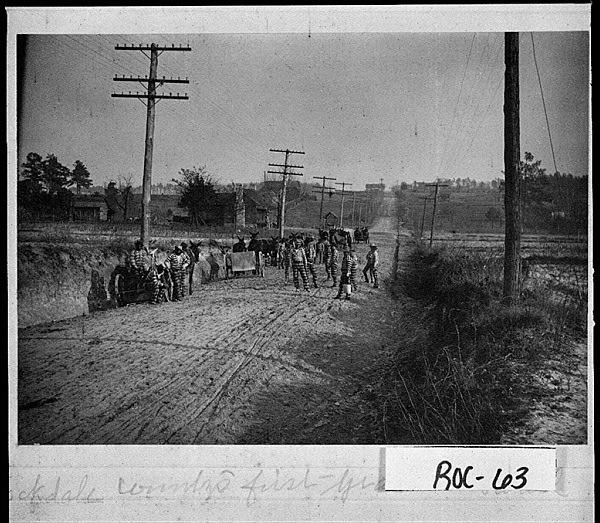

A native of Brooklyn, New York, Burns was a drifter and a battle-scarred World War I (1917-18) veteran who found himself living in a cheap hotel in Atlanta in 1922. In February of that year Burns and an accomplice stole $5.80 from a local grocer, Samuel Bernstein. They were arrested instantly; Burns was swiftly tried, convicted, and sentenced to six to ten years on the Campbell County (later Fulton County) chain gang. It did not take the stunned northerner long to comprehend that ten years on the chain gang was practically a death sentence. Southern chain gangs, notorious across the rest of the nation, had their origins in the scandalous convict lease system of the late nineteenth century. When convict leasing was abolished in 1908, with the demand for convict labor still growing, the chain gang took its place.

Burns’s book is full of sensational, lurid, yet mostly verifiable descriptions of mistreatment, brutality, disgusting food, and labor so unrelenting and exhausting that it left men in a stupor. As he soon learned from his wretched fellow prisoners that to leave the chain gang a man had to “work out, pay out, die out, or run out,” Burns decided to run out. He did so in June 1922, after serving only a few months’ time. Burns’s dramatic escape to Chicago was crowned by brilliant success in the publishing business, social recognition, and marriage. But years later when he proved an unfaithful husband, his wife, Emily, turned him in to the authorities. His arrest on May 22, 1929, caused a sensation in Chicago. Burns had never told Emily about his past, but she discovered his secret by opening letters from his brother, the Reverend Vincent Burns, an Episcopal priest.

In negotiations with officials from Georgia, Burns arranged to return to Georgia, take a soft job in the prison system, and receive a pardon after one year—or so he believed. But the state of Georgia was unrelenting, and Burns once more faced the hardships of the chain gang, this time at a prison in Troup County. In September 1930 he escaped a second time and made his way to Newark, New Jersey. There he wrote, “Georgia cannot win! . . . I have decided to write the true story, while in hiding, of my entire case.” Burns’s memoir, first serialized in True Detective Mysteries magazine, was published in January 1932 and was an instant success. “It would be hard to find a more thrilling story in either truth or fiction,” a New York Times reviewer wrote.

Some critics and scholars believe Burns’s brother ghostwrote the book. Vincent Burns, who was known mostly for his patriotic and religious poetry, served as the poet laureate for the state of Maryland from 1962 until his death in 1970. He also wrote Out of These Chains (1942), a sequel to I Am a Fugitive from a Georgia Chain Gang!, and The Man Who Broke a Thousand Chains: The Story of Social Reformation of the Prisons of the South (1968), a memoir of Robert Burns. Vincent Burns later sued his brother for a greater share of the profits received from the book and the film.

The Film

A motion picture version was put into production shortly after the book’s publication, directed by Mervyn LeRoy and starring one of Hollywood’s finest actors, Paul Muni, in the title role. Burns himself went incognito to serve as a consultant on the film. As indignant as Georgia officials were over the book’s publication, they were even more upset over the movie, and they insisted that Warner Brothers drop “Georgia” from the film’s title. Upon the movie’s release in late 1932—during one of the darkest periods of the Great Depression and days after the election of U.S. president Franklin D. Roosevelt—the theaters could not screen it often enough. A telegram to Warner Brothers in Hollywood told the tale: “fugitive biggest broadway sensation in last three years stop thousands turned away from box office tonight with lobby delay held four hours stop.”

In spite of its rather stilted script, the film was one of the major achievements of 1930s Hollywood. LeRoy had just completed Little Caesar, the first great work in a new genre, the gangster film, while Muni himself had just completed another classic gangster picture, Scarface. Thus, both star and director were moving from the founding of one genre toward establishing a second, the southern prison adventure. Fugitive was named Best Picture of the Year by the National Board of Review of Motion Pictures. Muni and the film received three Oscar nominations. It was remade in 1987 under the title The Man Who Broke 1,000 Chains (HBOFilms, directed by Daniel Mann). Scenes, themes, and motifs from the 1932 LeRoy picture also abound in Cool Hand Luke (1967, Warner Brothers, directed by Stuart Rosenberg).

Legacy

Burns was apprehended yet again in December 1932 in Newark, but the state of New Jersey refused to extradite him, despite the insistence of Georgia officials. After two other failed attempts to bring him back to Georgia, Burns met newly elected Georgia governor Ellis Arnall in New York in 1943 and requested a pardon. Arnall arranged to have Burns return to Georgia in November 1945 to face the parole board, where he stood by Burns’s side as his counsel. The board commuted Burns’s sentence to time served. Governor Arnall’s gesture capped an administration devoted to prison reform, including the abolition of chain gangs. Burns died on June 5, 1955, at his home in Union, New Jersey, where he had worked as a tax consultant.