In 1932 the radical journalist John Spivak published Georgia Nigger, a thinly fictionalized condemnation of Georgia’s penal system that unveiled the harsh working conditions and brutal treatment suffered by African Americans in the state’s convict camps.

Walter White, the executive secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), described Spivak’s novel as “the most devastating expose of the treatment of Negroes in the Georgia chaingang that has ever been written.” Nevertheless, Georgia Nigger was ultimately overshadowed by Robert Elliot Burns’s I Am a Fugitive from a Georgia Chain Gang!, which was published the same year.

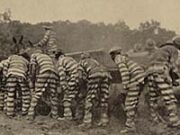

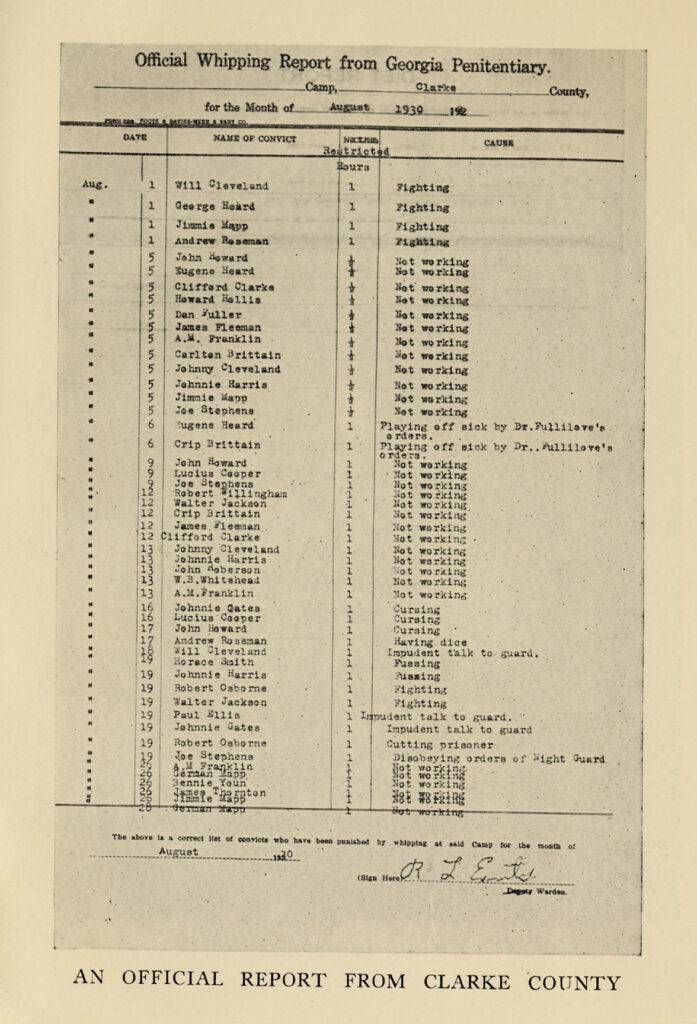

In 1930, when visiting the Georgia Prison Commission office in Atlanta, Spivak, a documentary reporter known for his investigative journalism during the Great Depression, surreptitiously photographed the “whipping reports” that detailed the punishment of convict labor on the road gangs. In response to a letter of introduction he obtained from the commission, camp wardens allowed him to document their skill in torturing recalcitrant prisoners. By 1930 Georgia had more than 8,000 convicts scattered in chain gangs that worked on the roads in 116 counties; three-quarters of these prisoners were Black. Failure to meet the demands of hard labor resulted in a whipping with a strap, the stretching of arms with a rope tied to a post, or confinement in a “sweat box.” Spivak documented these torments with photographs that accompany his novel. “America would not believe what I would say unless I could prove it with visual evidence,” he later wrote in his autobiography.

From Georgia Nigger, by J. L. Spivak

Fiction it may have been, but the New York Times found Georgia Nigger to have “the weight and authority of a sociological investigation.” During the 1920s Spivak had supported himself by writing for pulp-fiction magazines, learning in the process to embellish single facts into gripping stories. In Georgia Nigger he combined the style of pulp fiction with the radical documentary journalism of the 1930s, a form of writing he would use again in works like America Faces the Barricades (1935), which dealt with unions and labor relations.

Like many other works of “proletarian fiction” about the South in the 1930s, Georgia Nigger focuses on “the tenant farmer, hard working, but doomed to poverty,” in the words of the poet Sterling Brown. The fatalistic novel tells the story of David Jackson, a Black sharecropper’s son who finds himself caught between serving a chain-gang sentence and working in peonage for a planter willing to pay his fine. Returning home after a six-month stint on the chain gang, Jackson is caught on a Saturday night in a sheriff’s dragnet launched at the behest of Jim Deering, the most powerful planter in the fictional Ochlockonee County. Faced with a long wait in jail before the next court session, Jackson accepts Deering’s offer to pay his fine as an advance against wages. But after witnessing Deering murder another peon, Jackson flees. He is instantly picked up as a vagrant in the neighboring county and hauled into court; this time he chooses to work the roads for the county rather than return to the peon farm. The book ends with another failed escape attempt; Jackson is sentenced to a cruel spell in the “sweat box,” which confined convicts for a full day in an enclosed space under the blazing Georgia sun.

Georgia Nigger found an audience among both left-wing activists and mainstream readers. Spivak serialized his story in the Communist Party’s newspaper, the Daily Worker, and it also appeared in the Des Moines (Iowa) Tribune and the Milwaukee (Wisc.) Journal. Published in England and translated into French, German, and Russian, Georgia Nigger won Spivak renown in international left-wing circles in the 1930s. The book, along with the Atlanta trial of the African American communist Angelo Herndon in 1933, helped make the Georgia chain gang an often-cited example of southern racial injustice during the Great Depression.

Despite widespread serialization, favorable reviews, endorsement by the NAACP, and Spivak’s efforts to promote the book through the Black press, the Black church, and bookstore and lecture appearances, Georgia Nigger was eclipsed by Burns’s I Am a Fugitive from a Georgia Chain Gang! Burns’s story became the basis of a movie, and it was Hollywood’s popular version of social injustice that cast a national spotlight on the abuses of Georgia’s chain gangs, not Spivak’s more realistic documentary account. Unlike I Am a Fugitive, Spivak’s exposé asked Americans to confront the racial caste system that made the brutalities of the chain gang possible, something all too few were willing to do at the time.