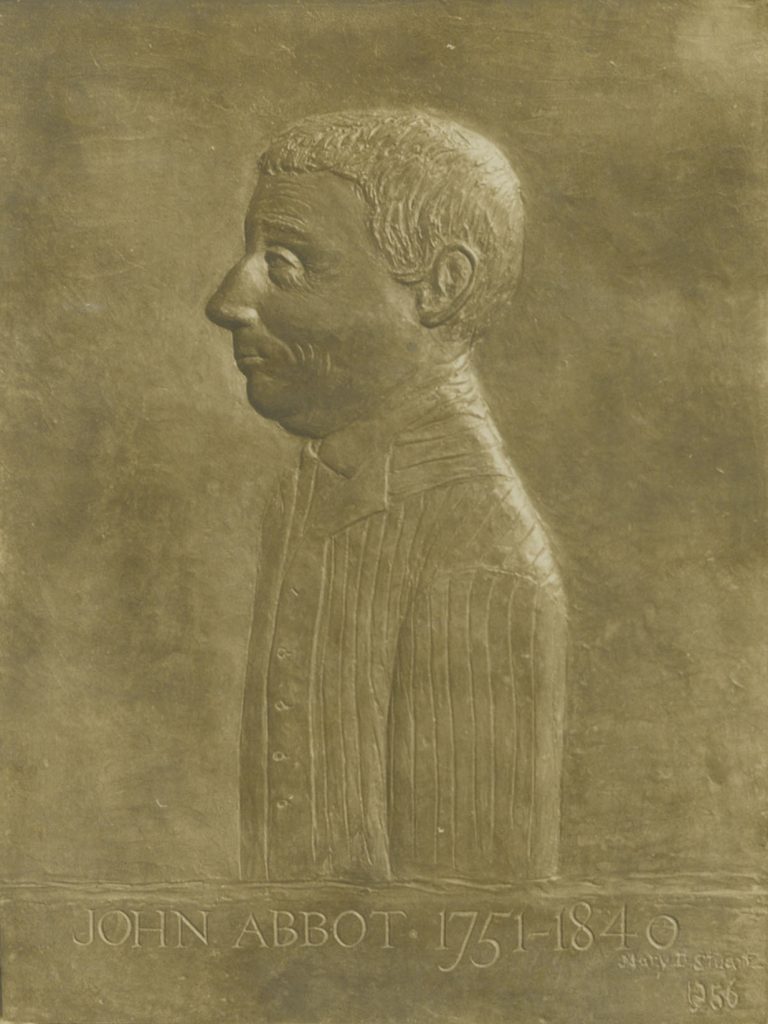

Naturalist and artist John Abbot advanced the knowledge of the flora and fauna of the South by sending superbly mounted specimens and exquisitely detailed illustrations of birds, insects, moths, and butterflies to collectors and scientists.

An autobiography detailing his early life was discovered after his death, but little information exists about the nearly sixty-five years he spent in Georgia. Although well known and revered during his lifetime, Abbot’s reputation has diminished because much of his work was published in England, kept in private collections, or contained in publications by others, unsigned. Nevertheless, Abbot’s carefully detailed drawings enabled scientists to accurately classify New World plants and animals, even though his nomenclature, or system of naming, varied from the standard system of plant and animal classification developed by Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus.

Early Life

Born in London, England, on June 11, 1751, into the prosperous family of Anne Clousinger and lawyer John Abbot, the young Abbot was expected to follow in his father’s profession. He spent around four years as a law clerk, but his love of nature, which developed during childhood, ultimately led him to a different vocation. He collected and bred insects and received art instruction from the engraver Jacob Bonneau. Later Abbot mastered the taxidermic skills needed to preserve and display insects, moths, and butterflies, and he studied his family’s art collection and library, which contained books of natural history. He was drawn to, and eventually became part of, the circle of natural scientists who lived in eighteenth-century London, where exotic plant and animal specimens arrived from Great Britain’s far-flung colonies. Two of his watercolor drawings of moths were exhibited with the Society of Artists of Great Britain in 1770.

Abbot, already familiar with a publication of the history of Virginia, decided to leave London for the colony, believing that it represented the shortest possible sea voyage to the New World. He sold his personal belongings and set out for the six-week journey aboard the Royal Exchange in the summer of 1773. Abbot left his homeland, never to return, armed with a letter of introduction from the Royal Society of London, an agreement with the London jeweler John Francillon to serve as his agent for the sale of specimens and illustrations, and commissions from several collectors and scientists.

During the voyage, Abbot befriended a couple who were settling in Hanover County, Virginia, a remote location one hundred miles from the mouth of the James River. He settled there as well and spent the next two years conducting a geological survey of the region while collecting and drawing approximately 570 different species of insects, butterflies, and moths. He perfected his mounting and shipping techniques, pinning the specimens and stuffing them with cotton in order to create a more lifelike appearance before placing them in a cork-lined wooden box, the false bottom of which provided storage for his illustrations. His packing and shipping methods protected his illustrations while keeping them hidden, the only way to avoid customs inspection and taxes. Abbot sent three collections to London, but only one arrived safely.

Life in Georgia

At the outset of the Revolutionary War (1775-83), Abbot, dependent on British connections for his livelihood, left Virginia in December 1775 amid escalating tension between England and the American colonies. He set out for St. George Parish (later Burke County) in rural Georgia, about thirty miles south of Augusta, where relatives of his Virginia friends owned land. Within a few years of moving to Georgia, Abbot married; had a son, John Abbot Jr.; and acquired land in Burke County, as well as other property.

In 1797 The Natural History of the Rarer Lepidopterous Insects of Georgia… Collected from the Observations of Mr. John Abbot was published in two volumes, edited by James Edward Smith, the founder and president of the Linnean Society of London. The first major work on North American insects, the volumes contain 104 etchings of watercolors of species that Abbot collected in the vicinity of his home between 1776 and 1792. Abbot’s work was also included in the Histoire generale et iconographie des lepidopteres et des chenilles de l’Amerique Septentrionale (1829-37), by J. A. Boisduval and J. LeConte, and in American Ornithology (1808-14), by Alexander Wilson. S. H. Scudder included a chapter about Abbot in his three-volume work The Butterflies of the Eastern United States and Canada (1889).

Abbot’s meticulous illustrations and careful writing chronicle the habitats, life cycles, behaviors, and migratory patterns of numerous species. He also advances theories concerning the relationship between predator and prey. His work enabled others to classify closely related species, several of which were named according to Linnean classification from Abbot’s specimens and drawings. Naturalist and evolutionary theorist Charles Darwin studied Abbot’s work prior to his own exploration of the New World.

Abbot lived and worked in Chatham County between 1806 and 1818. When the War of 1812 (1812-15) disrupted overseas commerce, Abbot sent his work to American collectors. After trade resumed, he once again sent work to Europe; in 1818 he moved to Bulloch County. Abbot continued to send drawings and specimens abroad until the mid to late 1830s, by which time he was widowed, in failing health, and living in reduced circumstances. He moved to the home of his friend William E. McElveen, whose plantation was located in Bulloch County. The final legal record of the artist is a document that concerns his will, dated October 24, 1839, which is housed at the Bulloch County Courthouse in Statesboro. Abbot was recorded in the census of 1840, and anecdotal information indicates that he died shortly thereafter. He is buried in the McElveen family cemetery.

Abbot’s Legacy

In 1957 the Georgia Historical Society placed a marker in the McElveen cemetery as a monument to Abbot and his work. Two species of spiders and one moth are named in his honor. The Southern Lepidopterists’ Society, established in 1978, bestows the John Abbot Award to an individual who has made significant contributions in the field.

All in all, Abbot produced more than 4,000 original watercolors depicting the insects, plants, and animals of Georgia, although fewer than 200 were published under his name during his lifetime. The Natural History Museum in London owns several thousand of Abbot’s watercolors, which were originally owned by John Francillon, Abbot’s agent. In the United States, Abbot’s watercolors can be found in the permanent collections of the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; the Atlanta Historical Society in Atlanta; the Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library at the University of Georgia in Athens; the Houghton Library of Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts; the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library of Emory University in Atlanta; and the Morris Museum of Art in Augusta. The Georgia Museum of Art in Athens holds thirty-five etchings from The Natural History of the Rarer Lepidopterous Insects of Georgia in its permanent collection.