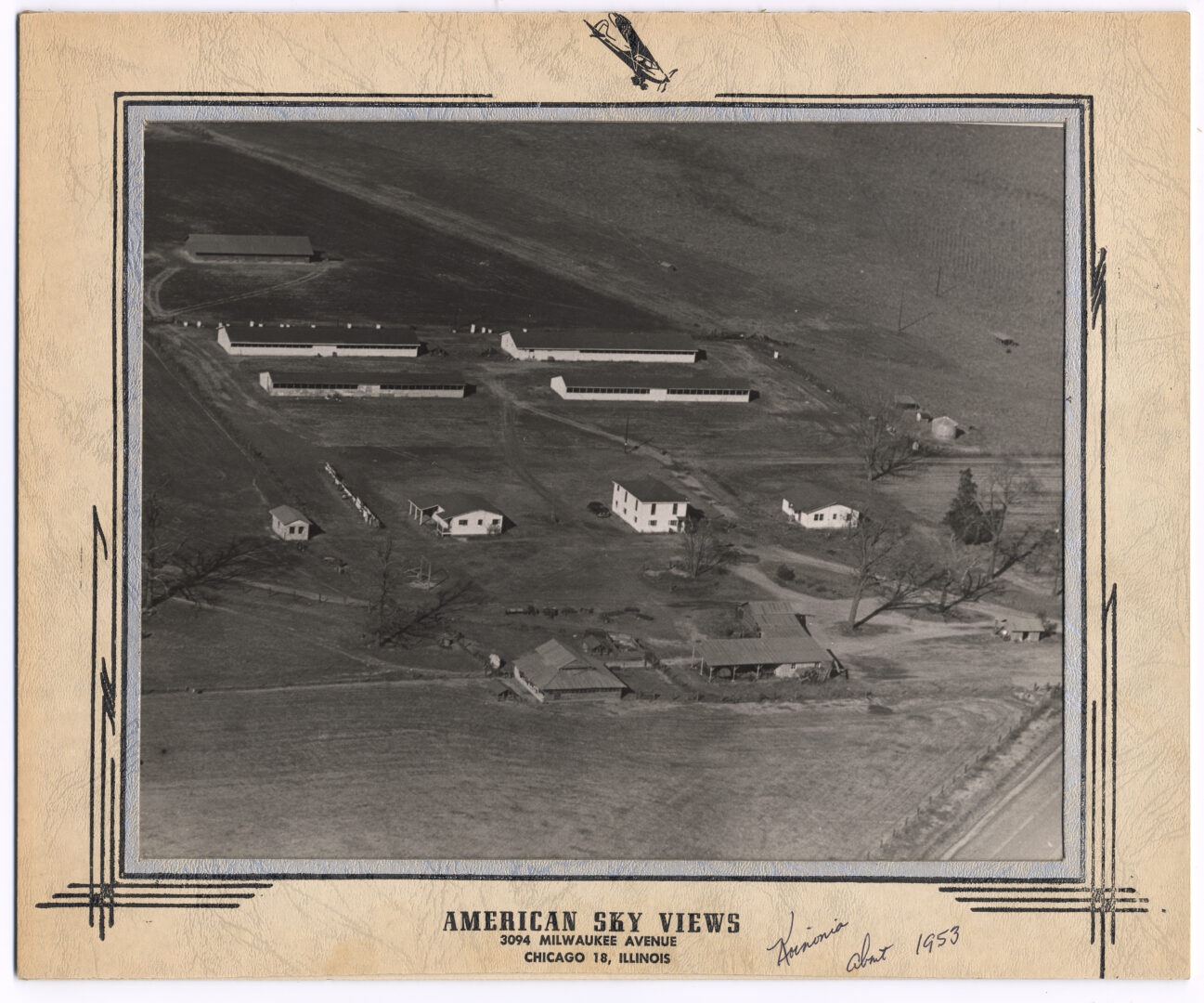

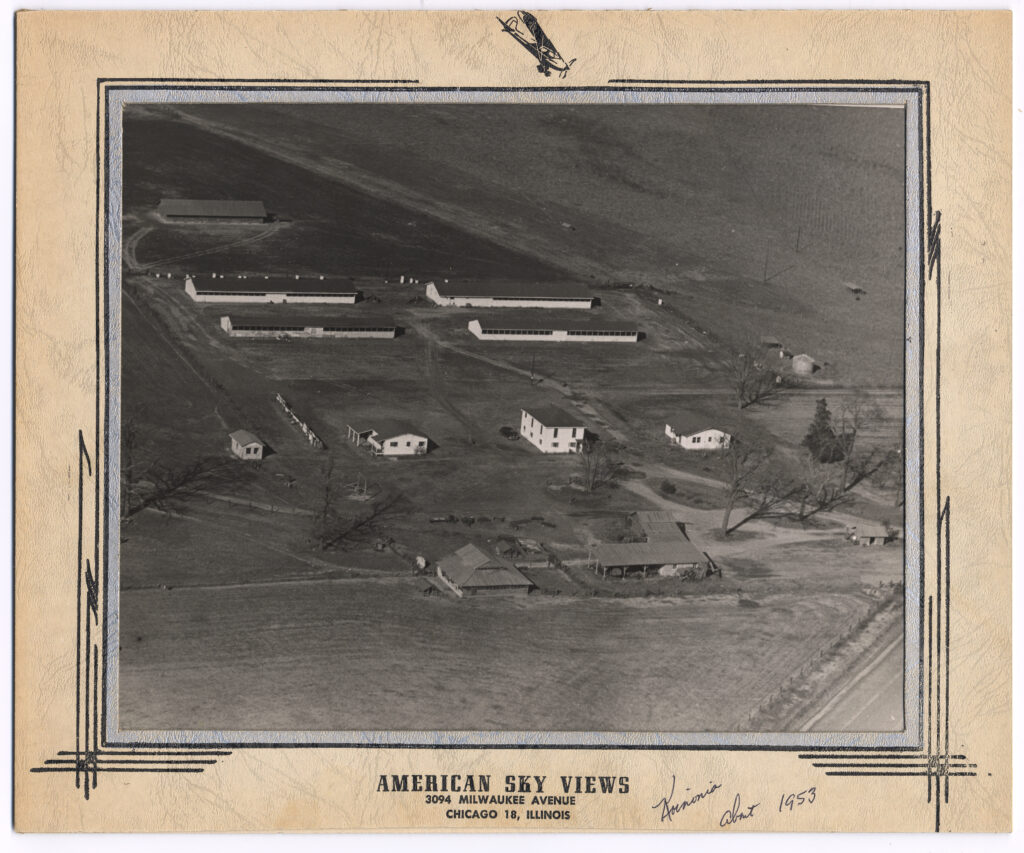

Attempting to live out the principles of pacifism, simplicity, and racial integration, a pair of white Baptist ministers and their wives, Mabel and Martin England and Florence and Clarence Jordan, established Koinonia Farm on 400 acres in rural Sumter County in 1942.

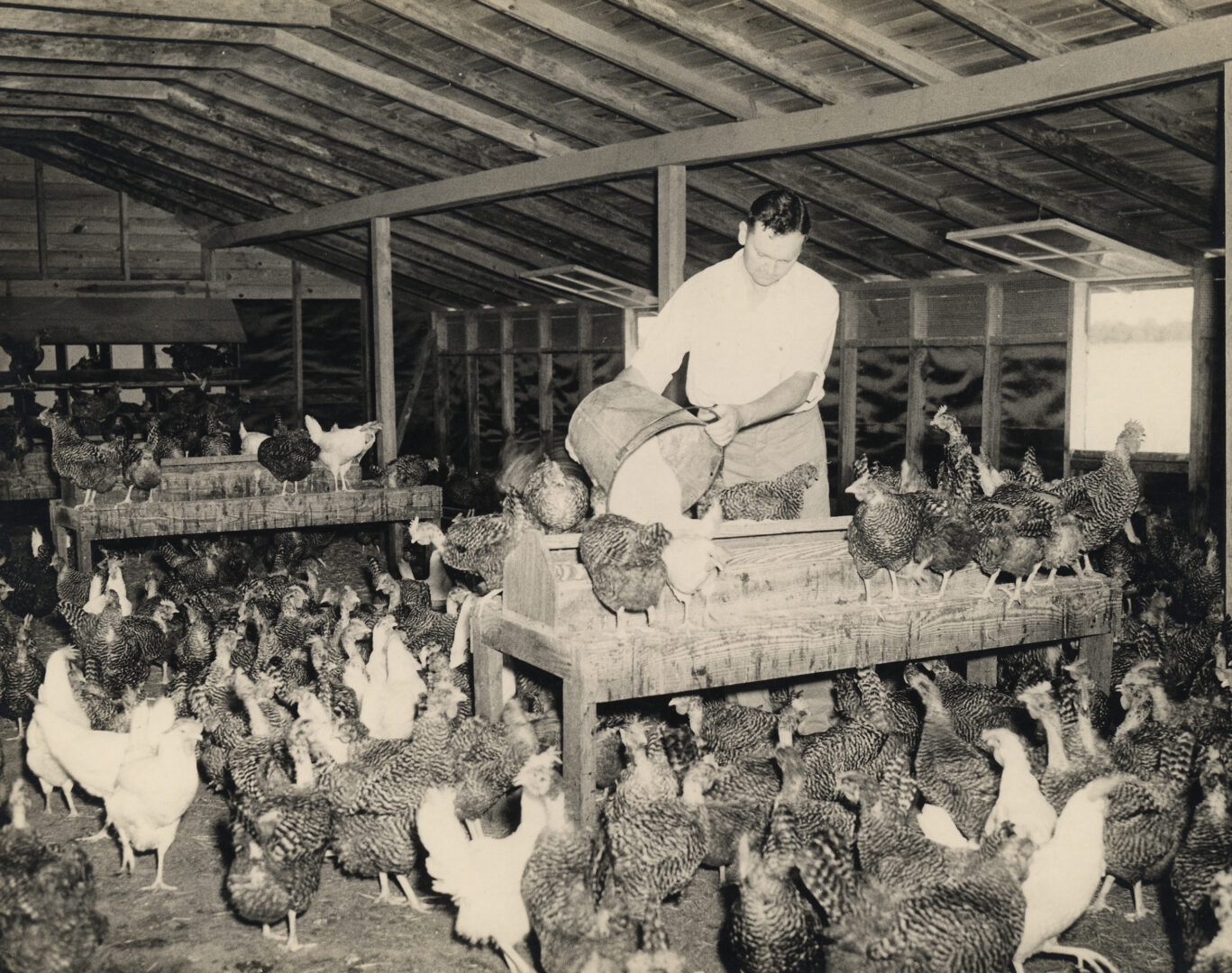

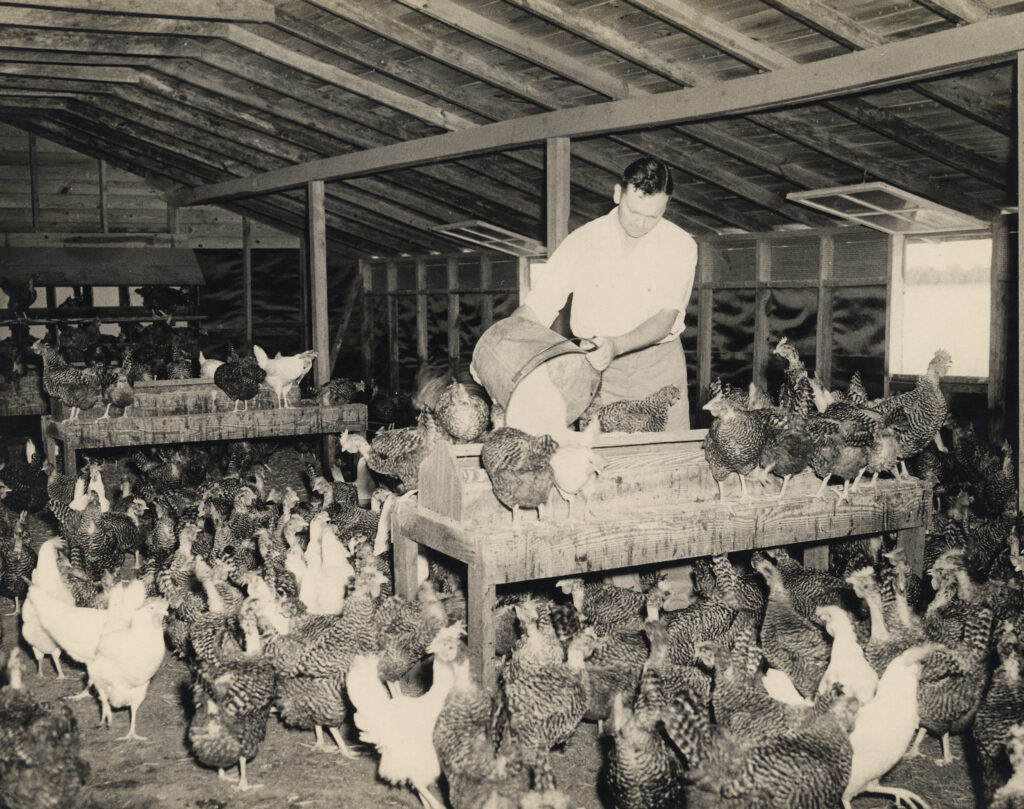

The ministers also hoped to teach improved farm practices. Named after the Greek word for fellowship and based on the early Christian church, Koinonia was to be a Christian community in which members pooled their resources into a common treasury and treated all persons as equals, regardless of race or class.

Early History

In Koinonia’s first year, curious neighbors visited England and Jordan to warn them that they were violating local customs by eating meals with their Black day laborers. Other Sumter County residents criticized Koinonia for welcoming conscientious objectors during World War II (1941-45). In 1950 the Rehobeth Baptist Church, just a few miles north of Koinonia, voted to remove the names of six Koinonians from its membership roll because church members perceived that the Koinonians were trying to integrate the church. In 1956 Jordan’s unsuccessful endorsement of the applications of two African Americans to the state university system’s Georgia State College of Business Administration (later Georgia State University) in Atlanta precipitated two years of vandalism, legal investigations, and violence, as well as a decade of economic boycott against Koinonia Farm. The successful farming enterprise halted. Koinonians developed a mail-order pecan business, which depended on purchases from people across the United States who had learned of Koinonia’s plight from the national news media.

By 1956 Koinonia’s population had grown from the original England and Jordan families to include approximately sixty people, although many were not full members. Most Koinonians were white Southern Baptists from areas of the South outside of Georgia, but about one-fourth were Black people who were primarily local. The decade of boycott and violence, inflicted by the Ku Klux Klan and others, dismantled the community until only two families, including the Jordans, remained. At the height of the civil rights movement, Koinonia Farm was essentially dormant.

Partners

Koinonia Farm was about to close when new leadership and new ideas revived it. In 1969 Jordan and Millard Fuller, a businessman, reincorporated Koinonia Farm into Koinonia Partners. They instituted a low-cost, interest-free building program that eventually constructed 200 houses in Sumter County. Over the years Koinonia’s landholding had expanded to include more than 1,400 acres, and part of the land adjacent to the center of Koinonia was divided into two neighborhoods that included many of these new houses. During the 1970s the number of Koinonia’s full members peaked at thirty-six, plus children and volunteers. Dozens of other people, however, bought the low-cost houses in Koinonia’s housing villages and became a part of its extended community. In 1976 Millard Fuller and his wife, Linda, left Koinonia to establish Habitat for Humanity International in nearby Americus. This organization implemented worldwide the house-building program pioneered at Koinonia. In 1979 Koinonia commissioned three families to establish a new intentional Christian community near Comer, in Madison County. This community, known as Jubilee Partners, primarily works with refugees from all over the world.

Koinonia celebrated its fiftieth anniversary in 1992 with a reunion that drew nearly 400 people. The community’s population had begun to decline in the 1980s, however, and by 1992 was at its lowest point in two decades. Soon after the anniversary, Koinonia shifted away from its communal practice to become a not-for-profit business. Unfortunately, embezzlement and mismanagement of funds throughout the 1990s saddled the community with a debt of $1 million. Along with donations, more than half of Koinonia’s land was sold to restore its solvency. In 2005, the board hired a new executive director, reverted back to the communal living envisioned by Jordan, and reclaimed the venture’s original name, Koinonia Farm.

Koinonia continues to operate the mail-order business and the farming enterprise, which it revived after the boycott lifted in the late 1960s. Koinonians have begun working on prison and death penalty reform as well. The community also holds regular reunions in addition to the Clarence Jordan Symposium.

Significance

Koinonia has persisted as an intentional community for more than seventy-five years, a long tenure compared with other communal endeavors in this country. Koinonians demonstrated a high level of flexibility both in the ways they worked for racial reconciliation and in the ways they restructured the community as circumstances changed. Koinonia still operates as a nonprofit organization, and its legacies of Habitat for Humanity and Jubilee Partners continue to address issues of human suffering around the world.