Near the end of the Civil War (1861-65), women from Columbus began to care for soldiers’ graves. One of them, Lizzie Rutherford, proposed an annual observance to decorate graves, inaugurating Confederate Memorial Day. Thirty years later one of the Columbus women compared their work to that of Mary Magdalene and the other women who came to Christ’s grave. In a way, this was an apt comparison, for what the women in Columbus were engaged in was no less than a new form of southern religion. Historians refer to this as Lost Cause religion, which was interdenominational and functioned as a culture religion.

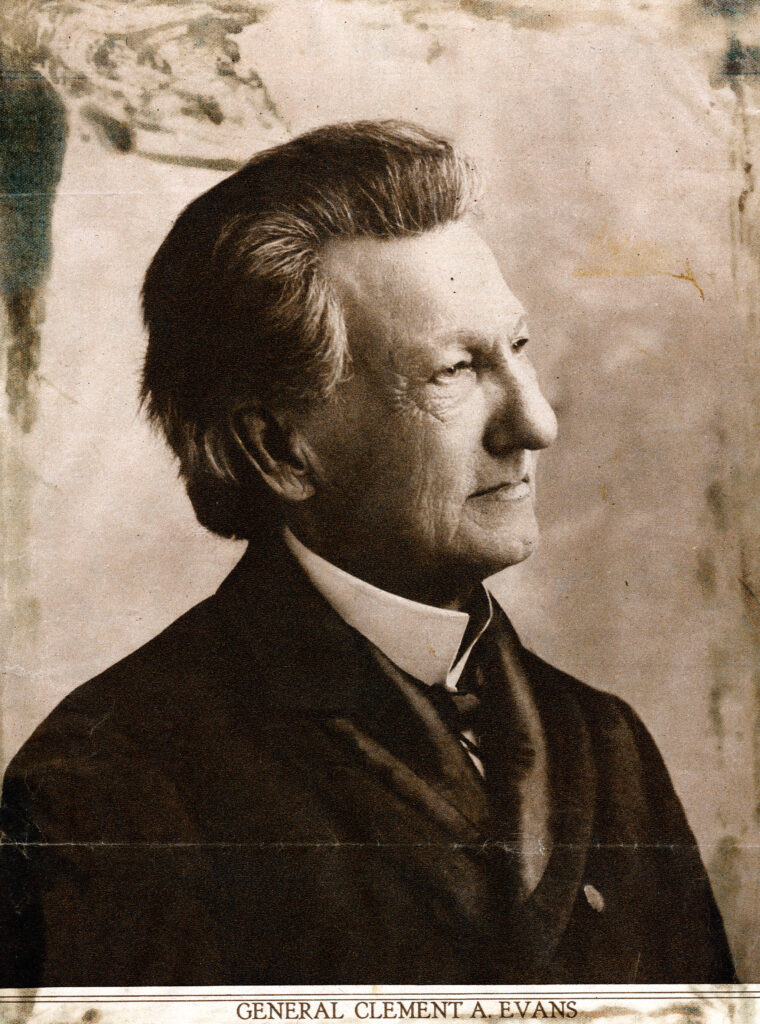

The term Lost Cause is not a modern invention but was used by southerners immediately after the war. Many scholars attribute the term to the Virginia journalist Edward A. Pollard and his postwar books, including The Lost Cause: A New Southern History of the War of the Confederates (1866). The Lost Cause concept supplied a heroic interpretation of the war so that southerners could maintain their sense of honor. As Georgian Clement Evans, a war veteran, put it, “If we cannot justify the South in the act of Secession, we will go down in History solely as a brave, impulsive but rash people who attempted in an illegal manner to overthrow the Union of our Country.” The assertion of the Lost Cause was the solution.

Courtesy of Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia Libraries.

The argument of the Lost Cause insists that the South fought nobly and against all odds not to preserve slavery but entirely for other reasons, such as the rights of states to govern themselves, and that southerners were forced to defend themselves against northern aggression. When the idea of a southern nation was defeated on the battlefield, the vision of a separate southern people, with a distinct and noble cultural character, remained. The term culture religion refers to ideals that a given group of people desire to strengthen or restore, and Lost Cause religion sought to maintain the concept of a distinct, and superior, white southern culture against perceived attacks. Major components of religion include myth, symbol, and their expressions through rituals. The Lost Cause culture religion manifested all three.

Myths

When scholars of religion refer to myth, they do not mean to imply a falsehood. Rather, in the context of religious studies, a myth is a foundational or sacred story, a story that explains. Lost Cause proponents knew well the power of myth. The main components of the Lost Cause myth, repeated in writings, sermons, lectures, and speeches by scores of postwar southern figures, are easily identified. First, the prewar South—the Old South—was a place of nobility and chivalry. (There is no better capsule description of the Old South of the Lost Cause myth than the opening words of the film Gone With the Wind, with its elegiac reference to the now-vanished pretty world “of Cavaliers and Cotton Fields,” where gallantry “took its last bow.”)

In a second component of Lost Cause dogma, the Civil War was recast as a defense of the South against aggressive, money-grubbing northerners. In Lost Cause mythmaking, the “War of the Rebellion” (as the federal government called it) became the “War of Northern Aggression.” While southerners were a people of honor and purity, Northerners were invaders, a people consumed by lust for power.

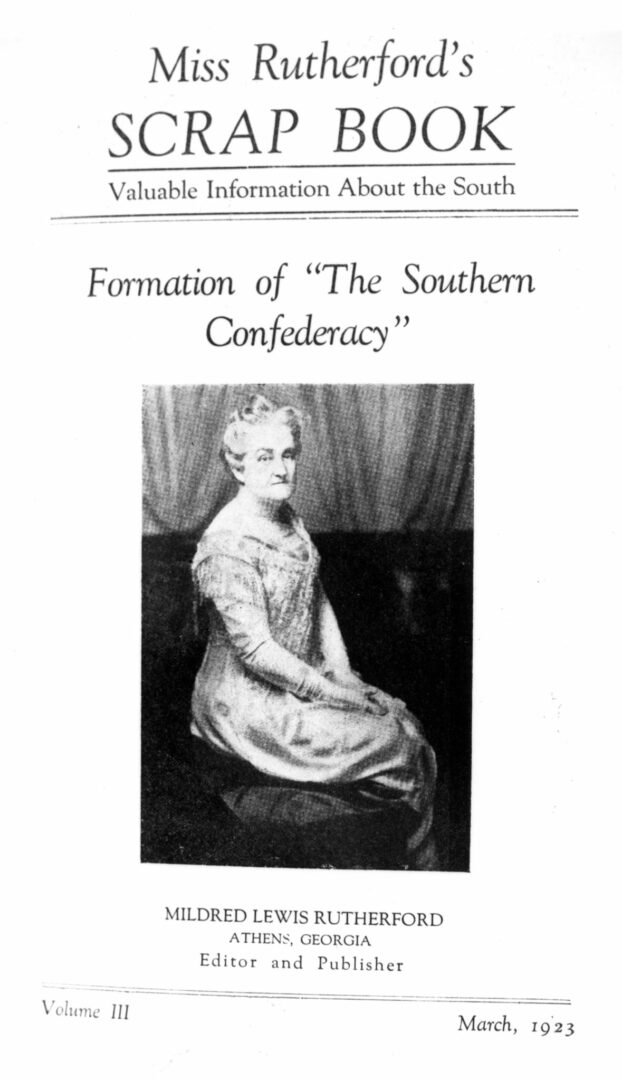

Finally, Lost Cause proponents preached the message that adherence to the civility of the prewar South meant that the Cause was not truly lost. Victory would come if white southerners maintained their superior and pure culture. The South need not be separate politically to rise again spiritually. This message was spread far and wide by agents of the Lost Cause, but perhaps no voice was as persistent and vocal as that of Georgian Mildred Lewis Rutherford, the longtime historian general of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, who tirelessly proclaimed the glories of the Old South. Her 1920 book, Truths of History, promotes a Lost Cause interpretation of the Civil War in opposition to what Rutherford viewed as the false claims of northern historians.

From Miss Rutherford's Scrap Book, vol. 4, April 1923

Symbols

Some of the major symbols of the Lost Cause are conveniently laid out in a Memorial Day address given in 1896 by Clement Evans, who, in addition to being a veteran, was also a Methodist minister and onetime commander of the United Confederate Veterans. Evans referred to “a deep and honorable respect for some things which we call our mementoes”; they are, he said, “sacred.” Limiting himself to “only three, each of which deserves our perpetual commemorations,” he listed the song “Dixie,” the Confederate battle flag, and the gray uniform of the South.

Living symbols of the Lost Cause may be added to Evans’s list, such as the Confederate soldiers and officers. Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee, and Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson each played a major role in the veneration of the Lost Cause and were often regarded as Moses and Christ figures by Lost Cause disciples. (These three figures are carved into Stone Mountain.) There was also a figure of evil in Lost Cause religion. Several Lost Cause proponents accused Georgian James Longstreet of losing the war by his actions at Gettysburg. In the process, Longstreet became identified as a Judas-like figure and was frequently denied the tributes customarily paid to Lee, Jackson, and others.

Photograph by Mark Griffin, Wikimedia

Rituals

In addition to Confederate Memorial Day, “the Sabbath of the South,” additional rituals honored Confederate veterans, especially the erection of Confederate monuments, which served as reminders of the Lost Cause throughout the year and as focal points for cultural memory. The historian Gaines M. Foster has identified 94 Confederate monuments that were erected in the South by 1885 (a further 406 were added by 1912). Some of the oldest of these monuments are in Georgia, such as the pillar in downtown Athens, which was erected in 1872. Perhaps the most storied Confederate monuments in the state are in Savannah, Atlanta, and Augusta. The Augusta monument contains what may be the most common inscription on Georgia’s Confederate monuments: “No nation rose so white and fair: None fell so pure of crime”—a Lost Cause sentiment to be sure.

Photograph by Elisabeth Hughes, New Georgia Encyclopedia

Such, then, are the major components of Lost Cause myth, symbols, and rituals. The Old South of Lost Cause myth was represented by symbols such as the Confederate flag and recalled through rituals such as Memorial Day. The culture religion was reinforced by the efforts of Confederate veterans, women, and mainstream religious figures. Among the latter, the premier example is J. William Jones, a Baptist minister known as the “Evangelist of the Lost Cause.” In a sermon given to a veteran group in 1900, Jones asked if “when the roll is called up yonder,” those assembled would be prepared to “’cross over the river and rest under the shade of the trees’ with Davis and Lee and Jackson and other Christian comrades who wait and watch for your coming?” For Jones and other adherents of the Lost Cause religion, Confederate heroism and Christian piety went hand in hand.