The Georgia division of the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) was formed on November 8, 1895.

Initially, the UDC worked both to maintain the beliefs of the Lost Cause, a heroic interpretation of the Civil War (1861-65) that allowed defeated white southerners to maintain their sense of honor, and to build monuments in honor of Confederate soldiers and leaders. The organization rapidly grew to include chapters in almost every town across the state and connected many middle- and upper-class white women across the South.

Origins

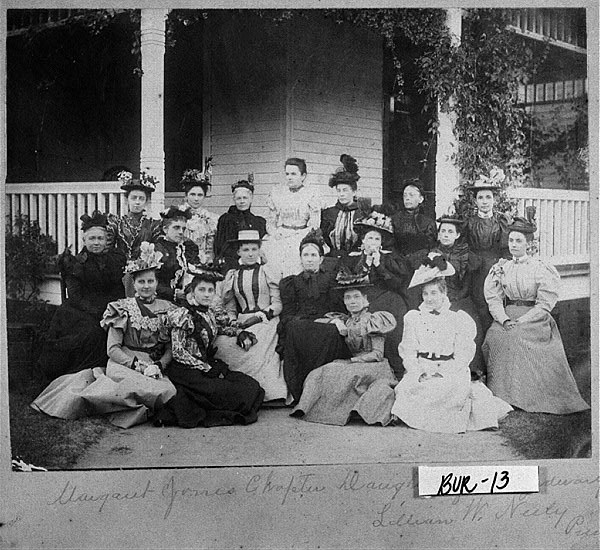

On September 10, 1894, Caroline Meriwether Goodlett, from Nashville, Tennessee, and Anna Davenport Raines, from Savannah, founded the National Association of the Daughters of the Confederacy. As a national federation of Confederate women’s organizations, the group brought together numerous women’s associations working to memorialize the Confederacy. At its second meeting, held in Atlanta, the group renamed itself the United Daughters of the Confederacy and revised its constitution. In 1895 the four chapters of Savannah, Augusta, Atlanta, and Covington united to form the Georgia Division of the UDC.

Positions within the national organization of the UDC included a president general, vice president general, recording secretary general, and historian general and were filled with women from various states. With its tight connections to powerful southern politicians, the UDC attracted a sizable and influential membership. Women who could prove they were blood descendants of those who served the Confederacy were eligible to join.

The UDC established five objectives delineating their memorial, historical, educational, benevolent, and patriotic responsibilities. Among other goals, UDC members strove to present what they considered to be a truthful history of the Civil War, to honor the Confederate dead, and to preserve historic Confederate sites.

Georgia’s UDC in Action

Prominent white women have been affiliated with the Georgia Division of the UDC since its founding. Although she died prior to the group’s establishment, Lizzie Rutherford is nonetheless closely associated with the organization. Rutherford pioneered the practice of decorating Confederate soldiers’ graves in the years immediately after the war, and to honor her legacy the Columbus UDC became the Lizzie Rutherford Chapter in 1898. This practice became an annual event became known as Confederate Memorial Day, and UDC members joined thousands of white people all across the South to visit graves, decorate headstones with flowers, and hold eulogy services. Indeed, early efforts were aimed at retrieving soldier’s bodies from northern battlefields, erecting tombstones in local cemeteries, and otherwise commemorating and mourning the Confederate dead.

Rebecca Latimer Felton, from Cartersville, spoke to UDC chapters throughout Georgia on a crusade to educate farm women in 1897. Aiming to empower poor whites and sustain notions of white supremacy, Felton argued that although farm women were not cultured like members of the UDC, they too were the descendents of Confederate veterans. She believed that rural girls, as future mothers of the white race, needed assistance and education. The UDC’s early efforts had focused on bereavement and graveyard commemorations, but these new programs propelled the UDC and its Lost Cause message into public spaces and the political sphere.

In 1898 another influential UDC member, Mary Ann Lamar Cobb Erwin of Athens, the daughter of Howell Cobb, envisioned a new way to honor Confederate veterans. Combining her efforts with those of Atlanta’s Sarah Gabbett, the women designed the Cross of Honor medal, which was first bestowed by the Athens chapter of the UDC on Erwin’s husband, Captain Alexander S. Erwin, in 1900. Nationally, the UDC bestowed thousands of crosses to veterans for honorable service. Today, they continue to present medals to veterans descended from Confederates as well as to libraries for display.

Athens native Mildred Lewis Rutherford was probably the most prominent member of the UDC. Like many members of the UDC in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Rutherford actively promoted white supremacy and led a tireless crusade in support of Lost Cause mythology, a civil religion that absolved the South of responsibility for the Civil War, rejected slavery as the war’s principal cause, and sentimentalized the practice of slavery. In her writings and speeches, Rutherford described Reconstruction as a litany of outrages and maintained that Black southerners were ill equipped for freedom and had fared better under slavery.

Despite her own public role, she strongly opposed to woman suffrage, and argued that the ideal white woman should be deferential to men and remain in the home. She believed that all women should hold the plantation mistress as the ideal version of womanhood.

Holding a deep and abiding commitment to white supremacy, Rutherford defended secession, supported segregation, vilified Black Americans, and otherwise glorified both the plantation system and slavery in antebellum Georgia. The textbooks she wrote, as well as her choice of which ones to censor, serve as a testament to a Confederate history that attempted to legitimize the authority of white southern elites while undermining Black Americans’s claims to full citizenship. From 1899 to 1902 Rutherford served as the Georgia Division’s president, and from 1911 to 1916 she served as historian general of the national organization. Rutherford Hall, a dorm building named in her honor, still sits on the University of Georgia’s campus.

Around 1915 Caroline Helen Jemison Plane, the president of the UDC Atlanta chapter, began the project that would culminate in the Confederate memorial carving on Stone Mountain. As leader of the Stone Mountain Memorial Association (incorporated in 1916 as the Stone Mountain Confederate Monumental Association), she solicited the support of the sculptor Gutzon Borglum and convinced the owners of the mountain to give the UDC access to the property. In addition to the carving of Confederate leaders, Plane wanted Ku Klux Klan (KKK) members to appear in the design. Controversies, sculptor changes, funding problems, and the outbreaks of World War I (1917-18) and World War II (1941-45) slowed the project’s progress, and the carving was not completed until 1970. Though it remains in place today, the carving has emerged as a point of contention in recent years, and an increasing number of activists and officeholders have called for its removal.

From 1953 to 1955 Mabel Sessions Dennis served as president general of the national UDC. Born in De Soto, in Sumter County, she held many positions in the group before leading the national organization. During her administration she organized the national [General] Children of the Confederacy. Comprising thousands of members today, the organization inducts children under the age of eighteen who can provide proof that they are descendants of honorable Confederate soldiers. The membership creed states a “desire to perpetuate, in love and honor, the heroic deeds of those who enlisted in the Confederate Services” and “teach the truths of history (one of the most important of which is, that the War Between the States was not a rebellion, nor was its underlying cause to sustain slavery).” Young members are provided a list of catechisms and “are encouraged to recite basic beliefs and elements of Confederate history.” The UDC also offers educational scholarships.

Recent Activities and Controversies

By the 100th birthday of the UDC in 1995, the national organization had elected seven Georgia women to serve as president general. In 2009 more than sixty-five Georgia divisions of the UDC existed. Although membership has waned in the twenty-first century, the organization actively recruits new members and those joining must still be a linear descendant of a Confederate soldier, militiaman, or musician. The vast majority of members are white southern women. Historians have largely debunked the myth of the Black Confederate soldier, but in 2014 a Black woman claimed Confederate ancestry and joined the organization; she was the first African American to join a Georgia UDC chapter.

Even in the twenty-first century, the ideals, activities, and purposes of the UDC have undergone only limited change. It continues to oversee the Children of the Confederacy organization and to hold memorial events and public programs. But the group’s most conspicuous legacy—the hundreds of Confederate monuments that dot the southern landscape—has come under increasing scrutiny. Critics of the group have increasingly tied its Lost Cause mythologizing to the rise of Jim Crow, and many have observed that Confederate monuments often served a dual purpose—honoring the Confederate dead and intimidating African American claimants to civil rights. For these reasons, cities and towns across the country have removed or relocated UDC-financed monuments commemorating Confederates, white supremacists, or slaveholders. The UDC has typically opposed these measures and remains an active participant in contentious debates over the nature and meaning of southern history.