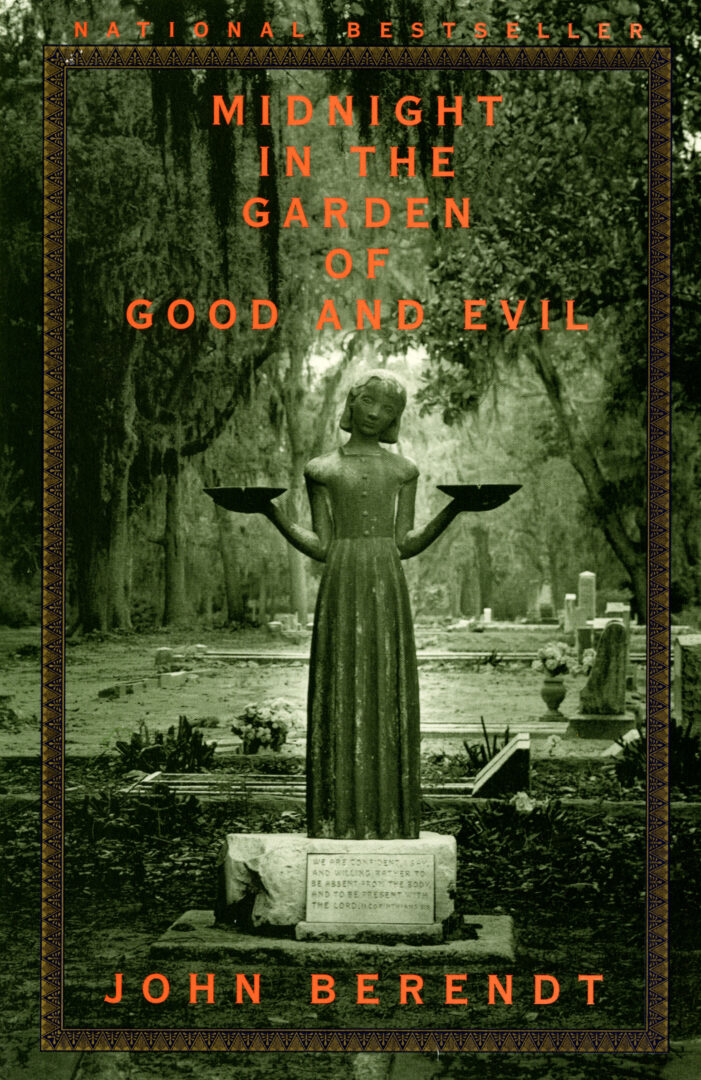

The impact of Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil on Savannah has been greater than that of any other book in the city’s history. Written by John Berendt and published by Random House in January 1994, the nonfiction narrative quickly became known locally as simply “The Book.” Since that time it has sold more than three million copies in 101 printings, has been translated into twenty-three languages and appeared in twenty-four foreign editions, and has brought hundreds of thousands of tourists to Savannah to visit this loveliest of crime scenes. The one point on which both critics and admirers agree is that, after Midnight in the Garden, Savannah’s clock will never be turned back.

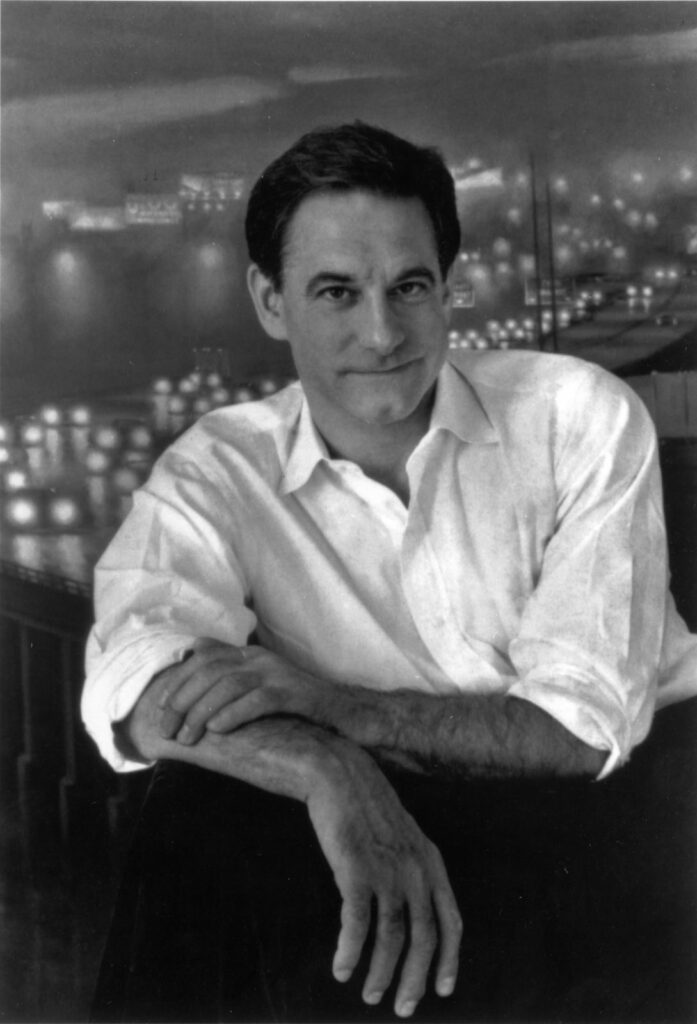

Author John Berendt was born in 1939 and grew up in Syracuse, New York; attended Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where he wrote and edited for the Harvard Lampoon; and was an associate editor at Esquire and editor of New York magazine before moving to Savannah in 1985 to research Midnight in the Garden. He took an apartment and for eight years lived off and on in the city, interviewing locals and gathering material.

The Book

The book is constructed loosely around the shooting of male hustler Danny Hansford by internationally known antiques dealer Jim Williams in May 1981 and the subsequent four murder trials that lasted more than eight years. Williams was finally acquitted, but the main interest of the story for many readers has been the wealth of exquisitely drawn incidental characters from every level of society and the artfully woven anecdotes that create a tapestry of Savannah.

Among memorable Savannahians depicted are singer/pianist Emma Kelly, “The Lady of 6,000 Songs” (so dubbed by Savannah songwriter Johnny Mercer); Joe Odom, a southern gentleman/lawyer who covers his bad checks with charm; an inventor (named Luther Driggers in the book) who possesses a vial of poison strong enough to kill the whole city if it were to infiltrate the water supply; Minerva, the Lowcountry “root doctor” who works spells for Jim Williams; Sonny Seiler, Williams’s defense attorney and owner of Uga, the University of Georgia’s renowned mascot; and The Lady Chablis, a drag queen who gleefully crashes an annual African American debutante ball.

Critical Reception

Reviews of the book almost unanimously praised the quality of the writing. The Savannah Morning News called it “a compelling, mordbidly fascinating, beautifully written book,” though the reviewer found the profusion of characters and anecdotes—however masterfully rendered—”overwhelming and overindulgent.” The same reviewer also lamented the lack of a “strong plot” to propel the action, as in “a conventional murder mystery,” and felt let down by the final ambiguity of whether the killing was murder or self-defense.

The Washington Post described Midnight in the Garden as “one of the most unusual books to come this way in a long time, and one of the best,” and the Los Angeles Times claimed that Berendt “seems congenitally unable to write a dull paragraph.” Of Berendt’s portrayal of Savannah, Newsweek stated, “Few cities have been introduced more seductively.” The New York Times Book Review agreed: “Mr. Berendt’s writing is elegant and wickedly funny, and his eye for telling details is superb…. Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil might be the first true crime book that makes the reader want to call a travel agent and book a bed and breakfast for an extended weekend at the scene of the crime.”

Legacy

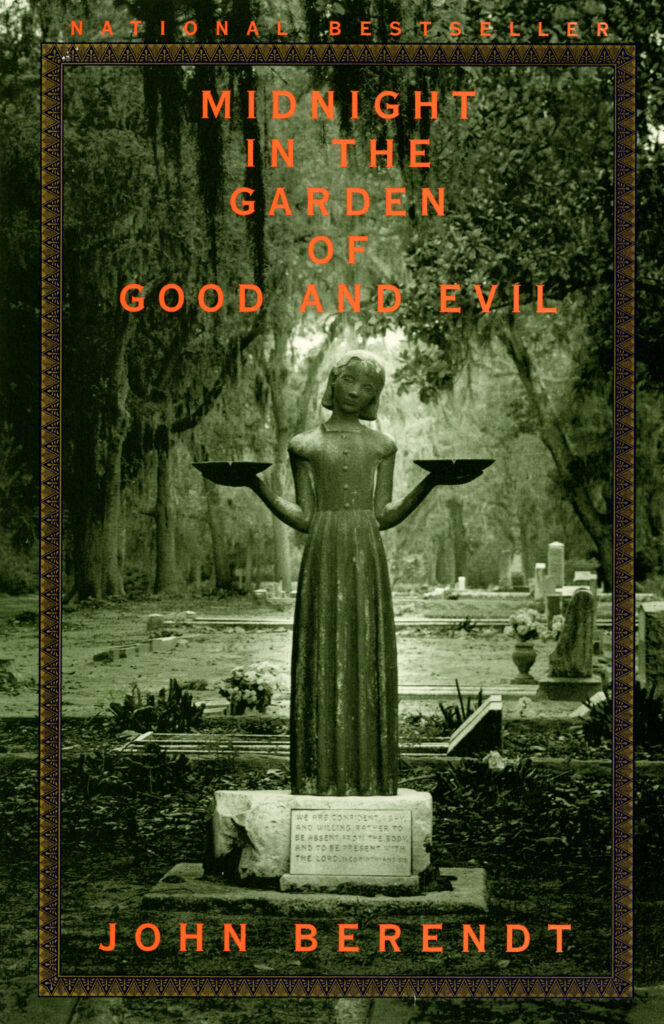

Tourists from all over the world have done just that, dispelling unequivocally a Savannah Morning News columnist’s early skepticism. Hotel-motel tax revenues rose about twenty-five percent in the two years following publication of the book, and cottage industries related to Midnight in the Garden sprang up like morning glories: trolley tours of the main sites; candles in the shape of the Bird Girl (photographed by Jack Leigh for the dust jacket); T-shirts, mugs, postcards, a newsletter, even a gift shop devoted specifically to Midnightabilia. On April 22,1996, the Savannah Economic Development Authority honored Berendt with a special award, and Mayor Floyd Adams declared April 26 of that year “John Berendt Day.”

The book won the Southern Book Award and was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in nonfiction, but without doubt its most significant achievement was the record number of weeks (216) it spent on the New York Times best-seller list. It also spawned a jazz concert based on Johnny Mercer songs, which toured the country in 1996, an eight-episode series on This Old House in 1996, and a two-hour A&E documentary titled Midnight in Savannah in 1997.

The Film

Warner Brothers bought the rights to the book, and John Lee Hancock wrote the script for the film. He showed it to Clint Eastwood, who had directed and starred in Hancock’s Perfect World (but who had not read Berendt’s book). On May 5, 1997, shooting began on Monterey Square in Savannah. The cast included Kevin Spacey as Jim Williams, Jude Law as Danny Hansford, John Cusack as the John Berendt character (renamed John Kelso), Paul Hipp as Joe Odom, Jack Thompson as Sonny Seiler (Seiler himself played the judge in the trial), Irma P. Hall as Minerva, and Eastwood’s daughter Alison as Mandy Nichols (a romantic interest of Odom in the book, of Kelso in the movie). Playing themselves in the film were Emma Kelly and The Lady Chablis, and Uga V, the University of Georgia’s bulldog mascot, played his sire. Jazz musician and Savannah native James Moody had a small role as Mr. Glover.

Savannahians filled many minor roles and rounded out crowd and party scenes. Eastwood made good use of the tree-lined streets and historic squares, and several scenes were shot at Mercer House itself (Williams’s mansion, built in the 1860s by Hugh W. Mercer, Johnny Mercer’s great-grandfather). The movie premiered in Savannah at the Johnny Mercer Theater on November 20, 1997, with Kevin Spacey, Paul Hipp, The Lady Chablis, and local actors attending, and it opened nationwide the following day.

Critical Reception

Reviews of the movie were generally lukewarm. Roger Ebert, after commending Eastwood’s “determined attempt to be faithful to the book’s spirit” and conceding “something ineffable is lost just by turning on the camera,” concluded that “the movie never reached takeoff speed.” Liz Smith (New York Post) found it “very long…. Judicious editing would help this movie a lot.” Desson Howe (Washington Post) observed, “You’re thinking about a graceful exit long before Eastwood even thinks to send you home.” Kenneth Turan (Los Angeles Times): “Listless, disjointed, and disconnected, this meandering, two-hour, 32-minute exercise in futility will fascinate no one who doesn’t have a blood relation among the cast or crew.” Performances by Spacey and Cusack were generally deemed good, considering the script’s flat lines, but only Jack Thompson’s Sonny Seiler was cited as Oscar-worthy. Even The Lady Chablis, ad-libbing most of her lines, seemed not quite herself.

Fortunately, the A&E documentary Midnight in Savannah, originally aired at the time of the movie’s release, succeeds resoundingly in portraying the city, the book, and its impact.