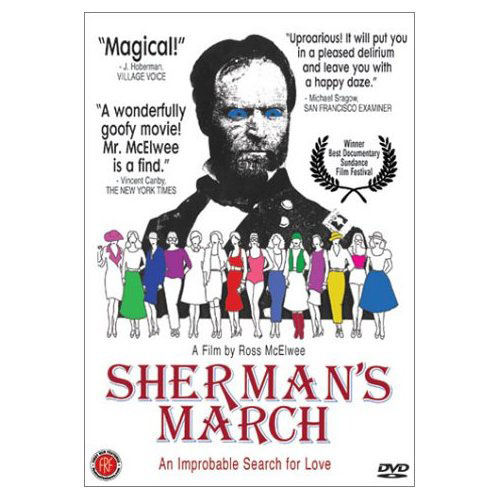

A well-loved and critically acclaimed work of cinema verite, Sherman’s March (1986) weaves together subjects as disparate as the Civil War (1861-65), nuclear holocaust, and southern womanhood to create a subtle and emotionally powerful film. Originally setting out to retrace Union general William T. Sherman’s march through Georgia and the Carolinas, documentary filmmaker Ross McElwee instead crafts an insightful look at life and the search for love in the modern South.

Born in 1947 in Charlotte, North Carolina, McElwee attended Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, as an undergraduate before enrolling in a graduate film program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). While at MIT in the mid-1970s, he studied under prominent documentary filmmakers Richard Leacock and Edward Pincus, from whom he learned the cinema verite techniques that he later used in Sherman’s March and other films.

After graduating from MIT, McElwee returned to Charlotte and worked for years as a freelance cameraman at local television stations, filming such various programs as the evening news and “Gospel Hour” shows. He also had the opportunity to work with legendary filmmaker D. A. Pennebaker and served as cameraman on John Marshall’s N!ai, The Story of a K!ung Woman (1980). During this time McElwee also made his own documentary films, including Space Coast (1979), Charleen (1980), and Backyard (1984).

Sherman’s March: A Meditation on the Possibility of Romantic Love in the South during an Era of Nuclear Weapons Proliferation is McElwee’s fourth documentary. In 1985 McElwee was set to begin work on a film about the lingering effects of Sherman’s march through the South. Before shooting began, however, McElwee’s girlfriend at the time ended their relationship. Despondent, he traveled to join his family on vacation in North Carolina, where he decided to take the advice of his sister DeeDee and use the camera as a way to meet women. The siblings’ conversation appears in the first few minutes of the film, and the rest of the movie records McElwee’s various attempts at meeting a “nice southern girl,” as he loosely follows Sherman’s route through the South.

During his journey McElwee encounters several interesting southern women, including Pat, an aspiring actress who asks him to film her sexually suggestive “cellulite exercises” and believes that Burt Reynolds, who has a cameo in the film, represents the ideal standard of southern manhood. McElwee follows Pat from North Carolina to Atlanta, where he attempts to start his film about Sherman by visiting Stone Mountain and filming scenes at the site of the 1864 Battle of Peachtree Creek.

Image from AdrianMcElwee

After Pat leaves for an audition in California, McElwee finds himself off the coast near Savannah, living for a while on a remote island with Winnie, a “hippie” linguist working on her doctoral degree. He also spends time in Charleston, South Carolina, with his friend and former teacher Charleen Swansea (the subject of his film Charleen), who tries to marry him off to a folksinger and devout Mormon who stockpiles supplies in case of a nuclear attack. All these relationships fail for one reason or another, and the film ends with McElwee back in Boston, without his Sherman documentary, discrediting the notion of actively searching for true love.

Several factors contribute to the success of Sherman’s March. First is the way in which McElwee forces himself into the narrative. While pure cinema verite technique dictates that the filmmaker simply shoot what is happening, McElwee learned from Leacock and Pincus that equally dramatic moments can happen when the filmmaker interacts with the subject, a technique he uses to great effect in Sherman’s March. One of the film’s most emotional moments occurs near the end when McElwee, whom the viewer to this point has seen only alone in staged shots or in mirrors, reaches out from behind his camera to touch the cheek of a woman distraught over a difficult relationship.

McElwee also engages the viewer through the use of several central metaphors and themes, such as the link he makes between his quest for love and Sherman’s life, and the connection he draws between failures in his romantic life and recurring dreams about nuclear holocaust.

Sherman’s March won several awards, including the Grand Jury Prize for Best Documentary at the Sundance Film Festival in 1987. In 2000 the Library of Congress National Film Registry chose the film for preservation, citing it as a “historically significant American motion picture.” McElwee currently teaches film at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and continues to make highly personal documentary films; in 2003 he released Bright Leaves, a documentary exploring his family history and tobacco farming in North Carolina.