Song of the South was Walt Disney’s film adaptation of African American folk tales written down in the late nineteenth century by Joel Chandler Harris in his Uncle Remus tales. The film opened at the Fox Theatre in Atlanta on November 12, 1946, to a gala premiere similar to the one given Gone With the Wind seven years earlier. The film combined 70 percent live action and 30 percent animation in a format that was technically advanced for its time, but it received mixed reviews for artistic merit and criticism for its portrayal of Black characters.

Production

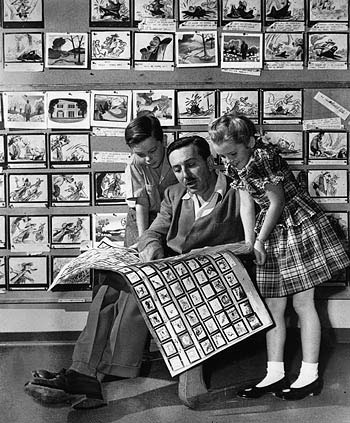

Walt Disney bought the rights to the Uncle Remus stories from the Harris family in 1939. Disney had high expectations for the film and hoped it would restore to his reputation some of the luster lost as a result of a series of unexceptional cartoon features in the early 1940s. The film was heavily researched, and separate directors were hired to handle the animated and real-life sequences. Thirty-six animators worked for two years on the animated sequences.

There was much discussion within the Disney studio about how the story and the African American characters should be presented. One of the scriptwriters, Clarence Muse—an African American—urged that Black characters in the film be portrayed in a positive light. He was so disappointed in the response he received that he resigned before the script was complete. That the studio was not concerned with making a racially progressive statement was perhaps reflected in its choice of James Baskett, an actor in the Amos and Andy radio show, to play Uncle Remus, and in Walt Disney’s comment to a colleague that he had hired a “swell little pickaninny” to play a Black child in the film.

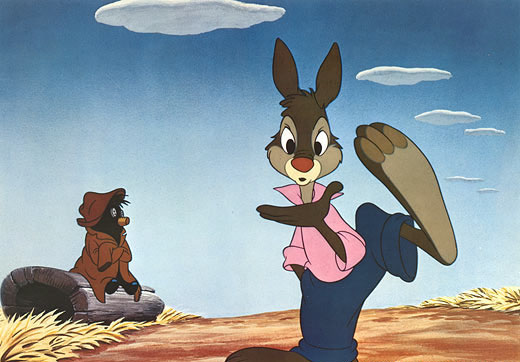

Song of the South concerns Johnny, a young white boy from Atlanta whose parents are separating. When he learns of the split while visiting his grandmother’s plantation, he tries to run away and encounters an elderly Black man, Uncle Remus, who tells him a Brer Rabbit story to persuade him to return home. A friendship develops, and Uncle Remus becomes for Johnny a substitute for his absent father and well-meaning but unaffectionate mother. When Johnny’s mother forbids him to see Uncle Remus, the old man decides to move away, and the boy runs after him. Attacked by a bull, the boy lies in a coma, unresponsive to his parents, until Uncle Remus visits and his words awaken the boy. At the end of the film, Johnny’s parents have reunited, and Uncle Remus and the children he has entranced are dancing down the road along with the animated characters from his tales. The animated sequences, reenactments of various Uncle Remus tales, are intended to instruct the boy in the importance of self-reliance, facing up to problems, and other values.

Reaction

Local reviews, including a notice in the African American newspaper the Atlanta Daily World, were largely positive, but nationally the film was not well received. Baskett was widely commended for his portrayal of Uncle Remus, but the other adult characters were seen as unremarkable. The live-action sequences in the film were criticized as boring, although the animated scenes received more praise. Film reviewer Bosley Crowther wrote that the movie was a “travesty on the antebellum South.” Another viewer wrote in an open letter to Disney, which was published by the Atlanta Constitution , “What’s got into you lately? Last night, I saw your latest movie, Song of the South. For a fellow with your talents, I thought it was a bum job. . . . This 'Uncle Tom’ musical hasn’t got it. . . . We felt embarrassed for you when we read that the colored actor who played 'Uncle Remus’ wasn’t permitted to attend the gala opening.” Others found the film mawkish, “slipshod,” and “inconsequential.” A never-resolved clash between the lighthearted animation and the real-life scenes about separating parents and fear of abandonment is clearly a problem in the film. The cartoon sequences and Baskett’s humane, genial performance are strong points.

Many reviewers took issue with the film’s portrayal of African Americans. The film does not make clear that the action is set shortly after the Civil War (1861-65), so that many viewers thought the black characters were enslaved people. Walter White, executive secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, wrote that the film gives a “dangerously glorified picture of slavery.” The National Negro Congress declared that the film “is an insult to the Negro people because it uses offensive dialect; it portrays the Negro as a low, inferior servant; it glorifies slavery.” Ebony magazine criticized the film’s “Uncle Tom/Aunt Jemima caricature.” Harlem congressman Adam Clayton Powell called on New York theaters not to show it. Disney defended it as a “monument to the Negro race,” pointing out that it was set after the Civil War and therefore could not be about slavery. Others found it entertaining, and a few praised its positive portrayals of Black and white individuals. Southern reviewers tended to like the film more than did reviewers from other parts of the country.

The film may not have intended a racist message and may well have sought to present harmonious relations between white and Black southerners. It does not acknowledge the racial problems of the post–Civil War South, however, nor does it suggest that its African American characters are anything but happy with their subservient roles. Baskett’s humane portrayal of Uncle Remus is counterbalanced by Hattie McDaniel’s more stereotyped portrayal of the house servant Aunt Tempy, and by several scenes in which groups of African American farm workers march happily home from the fields, singing in unison. Even the cartoon characters—Brer Rabbit, Brer Fox, and Brer Bear—are African American caricatures.

Song of the South won an Academy Award for Best Song, for “Zip-A-Dee-Doo-Dah,” by Allie Wrubel (music) and Ray Gilbert (lyrics). Although he was not nominated in the acting category, Baskett was honored in 1947 with a special Oscar by the Academy for “his able and heartwarming characterization of Uncle Remus, friend and storyteller to the children of the world.” He died four months later, at the age of forty-four. Other actors in the film included Hattie McDaniel (who played Mammy in Gone With the Wind), child star Bobby Driscoll, Ruth Warrick, and Erik Rolf.

Commercially, Song of the South was a success. Ticket sales were strong in its first run in 1946 and in the subsequent releases in 1956, 1972, 1980, and 1986. Its total gross income by the twenty-first century was approximately $60 million worldwide. The controversy surrounding the film has discouraged other releases, however, and it is not available for commercial sale in the United States.