Poet, playwright, and short-story writer Turner Cassity earned fame for his prolific publication of formal poetry. His work shares sentiments with the New Formalist movement that matured in the 1980s, exhibiting such characteristics as an avoidance of the autobiographical, a preference for meter and rhyme over free verse, stylized language, and the unfolding of a poem through narrative. Cassity’s verse is known for its wit, humor, stringent satire, and iconoclastic views, as well as for its musicality.

Early Life and Career

Allen Turner Cassity was born on January 12, 1929, in Jackson, Mississippi, to Dorothy and Allen Cassity. Raised a Calvinist, he grew up in Jackson and Forest, Mississippi. His grandparents on both maternal and paternal sides were in the sawmill business. His mother, a violinist, and his grandmother, a pianist, were silent movie musicians. Cassity’s father died when he was four, and at the age of sixteen he began managing his own inheritance. He attended Millsaps College in Jackson, graduating in 1951, and then enrolled at Stanford University in Stanford, California, earning a master’s degree in English in 1952.

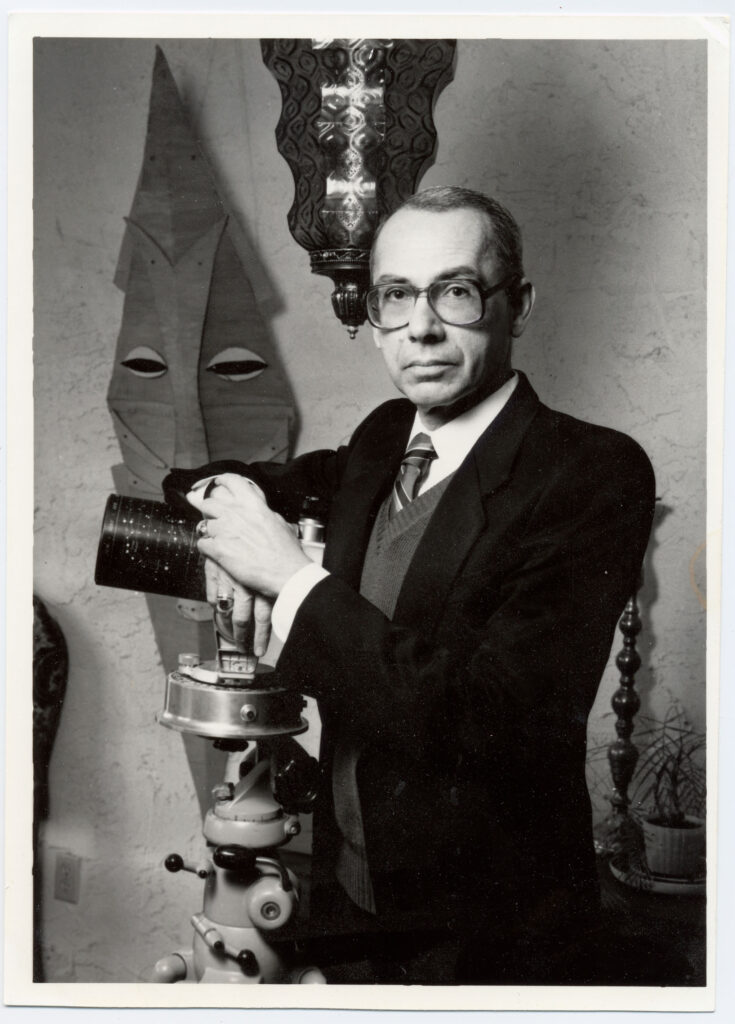

Courtesy of Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University.

From 1952 to 1954, toward the end of the Korean War (1950-53), Cassity was drafted and stationed in Puerto Rico. After leaving the military, Cassity attended Columbia University in New York City on the GI Bill and received a master’s degree in library science in 1955. After graduation he worked for the Jackson Public Library and then moved to South Africa, where he worked from 1958 to 1960 as a librarian, first in Pretoria and then near Johannesburg. He then returned to the Jackson Public Library for one year before spending four months in Europe.

In 1962 Cassity accepted the position of librarian in the Robert W. Woodruff Library at Emory University in Atlanta, from which he retired in 1991. He also cofounded the Callanwolde Readings Program, which highlights poets and writers, with poet Michael Mott.

Cassity started writing poetry at the age of fifteen. His books include Watchboy, What of the Night? (1966); Steeplejacks in Babel (1973); a verse play Silver Out of Shanghai (1973); Yellow for Peril, Black for Beautiful (1975); The Defense of the Sugar Islands (1979); Phaethon unter den Linden (1979); Keys to Mayerling (1983); The Airship Boys in Africa (1984); a verse play The Book of Alna (1985); Hurricane Lamp (1986); Lessons (1987); a book-length poem To the Lost City, or, the Sins of Nineveh (1989); Between the Chains (1991); The Destructive Element: New and Selected Poems (1998); No Second Eden (2002); and Devils and Islands (2007), for which Cassity received a Georgia Author of the Year Award from the Georgia Writers Association. He also received the Levinson Prize for Poetry, the Michael Braude Award of the American Academy of Arts and Letters, the Ingram Merrill Foundation Award, and a National Endowment for the Arts grant.

Style, Form, and the Modern South

Cassity’s writing exhibits a voice that is impersonal, sober, and gritty and a language that is at once “clear and mysterious,” as critic J. D. McClatchy observes. From Yvor Winters, his teacher at Stanford, Cassity acquired a penchant for both moralism and metrical rigor. A typical Cassity line runs in couplets, but tercets, quartets, and blank verse, among other variations, also appear in his work. His poem “In Sydney by the Bridge,” commonly regarded as Cassity’s ars poetica, compares verse to the ferry and vers libre to the cruise ship, and hints that “the scheduled ferry, not the cruise ship, [is] precious,” for the former is free from detours. Another poem, “The Metrist at the Operetta,” indicates that formal verse allows enough freedom for creation since “in the arts / [i]t is the tricks that are the trade.”

Cassity’s views of the South were iconoclastic, despite his use of traditional literary forms. Though a poet from the Bible Belt, he asserted that a poet should be more than a mere teller of moral tales. In “By the Waters of Lexington Avenue,” Cassity likens a poet to a steeplejack who builds the modern tower of Babel, a symbol of humanity’s “will to power” erected to conquer “the quotidian.” To Cassity a poet sings the “[t]wanging sound” of “the elevator cables” sending people up nearer to God.

Moreover, in Cassity’s opinion, the meaning of “the South” has broadened and transformed as southerners have traveled and colonized the country and the globe, suffusing new lands with southern regionalism. His poem “Cartography Is an Inexact Science” accentuates his idea of cultural syndication by suggesting that geography is defined more by people’s interrelationships than by space: “We thrive a little, one the other’s climate, / Our two backs / A sort of landfall.” Cassity’s poetry depicts a postcolonial South in which sin, avarice, pride, and morality unveil themselves in exotic outposts, in the interplay of colonial forces of the past and postcolonial lives of the present.

Cassity considered himself a southerner yet disagreed with the notion that southernness is merely a “literary convention,” since such a convention can no longer describe modern southern life. Rather than continuing the myths of a tragic and guilt-ridden South evoked by William Faulkner and other writers, Cassity’s poetry implies that southern writers can and should reinvent their language and subject matter.

Considered by poet and critic Dana Gioia to be perhaps the “most brilliantly eccentric poet in America,” Cassity continued to use traditional literary form to express his complex and imaginative vision until his death. He died in Atlanta on July 26, 2009, and was buried in Forest, Mississippi.