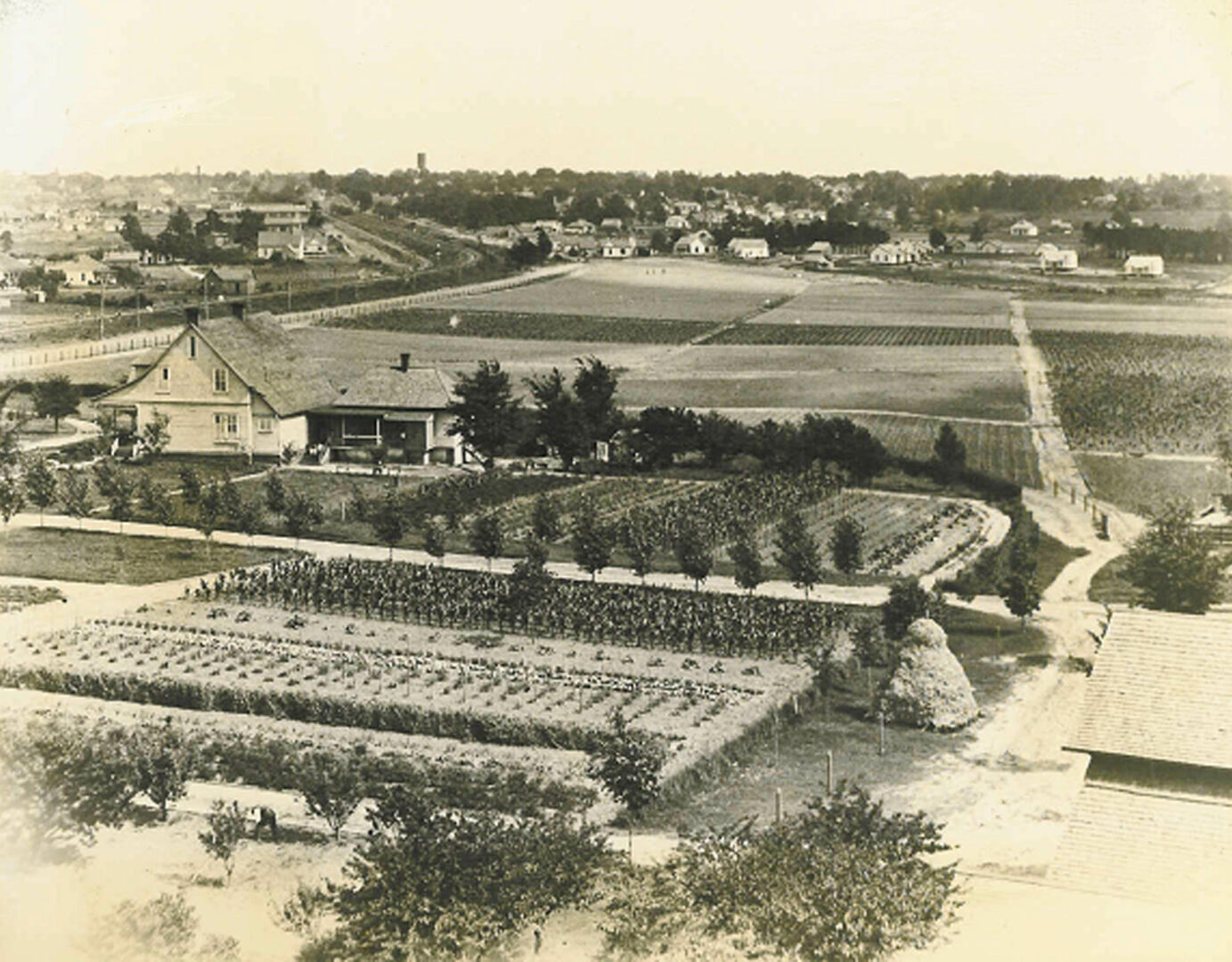

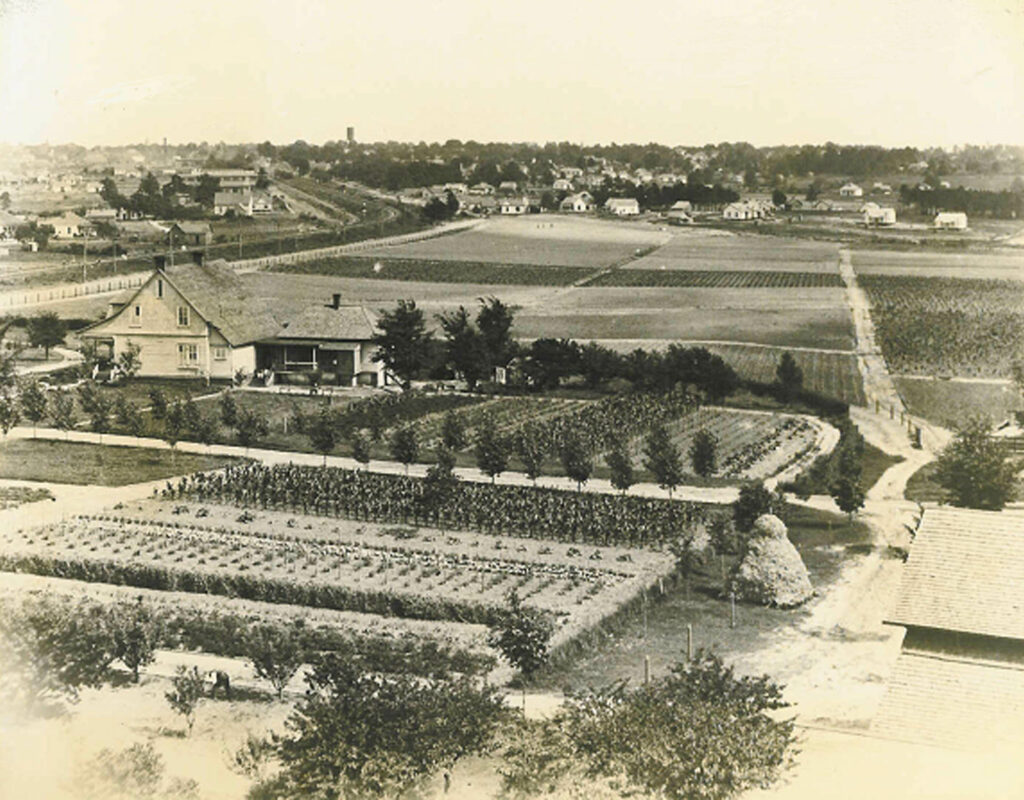

Since 1888 the Georgia Experiment Station in Griffin has played an important role in the development of modern agriculture in the South. Located forty miles south of Atlanta, in Spalding County, the station was established as a result of the federal Hatch Act of 1887, which established a national network of agricultural experiment stations. Spalding County citizens lobbied for the experiment station to be located in their county on land formerly known as the Bates Farm. Early research focused on fertilizers and soil erosion, but eventually a complete program of agricultural and environmental science research developed. The first director of the station was William Louis Jones, a scientist and journalist.

Achievements

Scientists at the experiment station began to solve problems associated with many Georgia crops and as a result significantly improved the state’s agribusiness. The deep furrow method of planting winter oats, pioneered around 1900, saved southern farmers millions of dollars. The first formulated feed diets for dairy and beef cattle in Georgia were discovered in Griffin in the early twentieth century. Griffin scientists also bred numerous crop varieties, including Empire cotton, which was released in 1942 and had a major impact on cotton growers in the state. In the 1940s Jasper Guy Woodroof, who organized the station’s food science department and later became known as the “Father of Food Science,” developed the technology for frozen foods.

Courtesy of University of Georgia College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences

Research

Today, the experiment station is one of the region’s premier agricultural research centers, poised to address the research, extension, and teaching needs of the twenty-first century. Scientists still address issues ranging from production agriculture to water quality and genetics. The experiment station is one of three agricultural research stations operated by the University of Georgia College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences; the other two are the University of Georgia Tifton campus (formerly the Coastal Plain Experiment Station) and College Station in Athens. Griffin researchers work with their counterparts at the stations in Athens and Tifton to solve problems that continue to challenge farmers, commercial growers, the food industry, and consumers. Researchers at the experiment station focus on five broad areas: crop and pest management, food safety and quality, environment and natural resources, urban agriculture, and applied plant genetics.

Courtesy of University of Georgia College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences

Georgia’s long, frost-free growing season, diverse soils, and variable rainfall are of great benefit to growers, but these factors also contribute to insect, weed, and crop diseases. Such pests limit crop growth, reduce yields, damage stored products, destroy aesthetic beauty, and threaten homes and structures as well as the health of humans, livestock, and pets. Station researchers develop, implement, and evaluate crop and pest-management programs that are effective, environmentally compatible, and economically rewarding.

Image from UGA CAES/Extension

The delivery of safe, high-quality food is another major research focus at the station. Food is not only the most basic of necessities but also is big business. Research in this area emphasizes the performance of systems that move food to the consumer. Station scientists work to ensure food safety, improve its quality, and minimize its marketing costs. To support this mission, the University of Georgia established the Center for Food Safety at the Georgia Experiment Station in 1993. The center’s faculty work with food industry and commodity research boards to address food quality and safety issues.

Researchers also address the nation’s concerns over water quality and availability, the ecological and human health effects of agricultural chemicals, and the evolving resistance to pesticides, in addition to debating such issues as wetland conservation and global warming. Their work focuses on providing an economically successful production system that improves the quality of life in rural and urban communities without degrading the environment.

Courtesy of University of Georgia College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences

Researchers study the effects of environmental factors on plant growth. Much of this research is being conducted at the experiment station’s Georgia Envirotron facility, which allows researchers to control such factors as temperature, humidity, and carbon dioxide levels. Controlled environmental research examines the effects of carbon dioxide elevation, pollution, heat, and drought stress, as well as the effects of vegetation’s toxic-gas emissions into the environment. Data from the station’s Georgia Automated Environmental Monitoring Network also proves invaluable weather-related information for environmental research.

Image from UGA CAES/Extension

In recent years, the most dramatic changes in landscape patterns in the United States are associated with rapid urbanization. North and central Georgia are included in a national urbanization “hotspot.” In addition to breeding new turfgrass varieties, researchers are looking for ways to control such urban pests as termites and fire ants. Georgia residents spend an estimated $420 million annually to control and repair damage caused by household and structural insect pests. At the Georgia Center for Urban Agriculture, located at the Georgia Experiment Station, scientists are developing efficient, low-input, and environmentally sound management systems, maximizing plant quality and adaptability, promoting environmental stewardship, and conducting economic assessments.

Harmful insects and diseases are significant problems in the Southeast, so crop improvement and pest management through plant breeding are continuously needed. The Georgia Experiment Station’s breeding programs are directed toward the development of new varieties of turfgrass, small grains, ornamentals, muscadine grapes, and canola. Breeding efforts also focus on the development of plants with resistance to heat and drought stress as well as to low winter temperatures and insects that have adapted to the Southeast.

Through the Plant Genetic Resources Conservation Unit, the U.S. Department of Agriculture maintains a repository of more than 84,400 germ-plasm samples of peanut, pepper, melons, cucurbits, sweet potatoes, and forage grasses at the Griffin campus. The wild relatives of these cultivated crops are also included in the collection and possess potentially important genetic traits, such as disease resistance, which can be transferred to cultivated varieties. This germ plasm is available to plant scientists worldwide for use in breeding new crop varieties.