Interface is the world’s largest manufacturer of commercial carpeting. The firm is based in Atlanta (corporate headquarters) and LaGrange (home of core business Interface Flooring Systems), and has annual revenues consistently in excess of $1 billion. Founded in 1973 by Ray Anderson, Interface has grown into one of Georgia’s largest corporations, with manufacturing facilities located in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia.

Courtesy of Interface

This global company grew from distinctly regional roots and provides a solid example of the long-term benefits of the South’s textile-mill-building crusade of the late nineteenth century. While the region’s once dominant cotton mills have been in decline for decades, occasionally a creative, innovative offshoot appears. Northwest Georgia’s tufted carpet industry grew from the region’s textile traditions in the 1950s, developing new technologies and products. Interface was a part of this carpet boom. Even within the emerging carpet industry, however, Interface carved out a specialized market niche in its early years. In recent years Interface has become a leader in the movement for sustainable development, instituting pioneering environmental policies.

Interface founder Ray Anderson is a Georgia Institute of Technology graduate with a degree in industrial engineering. He spent fourteen years, from the late 1950s through the early 1970s, working for Troup County’s Callaway Mills and the firm that eventually bought Callaway, Deering-Milliken. While at Deering-Milliken, Anderson worked on a joint venture with Carpets International, a British firm, to develop a European technology for producing free-laying carpet tiles—eighteen-by-eighteen-inch squares of carpet that could be laid in a variety of patterns with no adhesive. Carpet tiles seemed ideal for commercial applications—office space, for example. Inevitably, some areas of a carpet wear more quickly than others, because of variations in traffic, amount of direct sunlight, and other factors. Individual tiles could be replaced more cheaply than whole carpets. After helping develop a carpet tile business for Deering-Milliken, Anderson left his longtime employer to start his own business, then called Carpets International Georgia, in LaGrange.

Courtesy of Interface

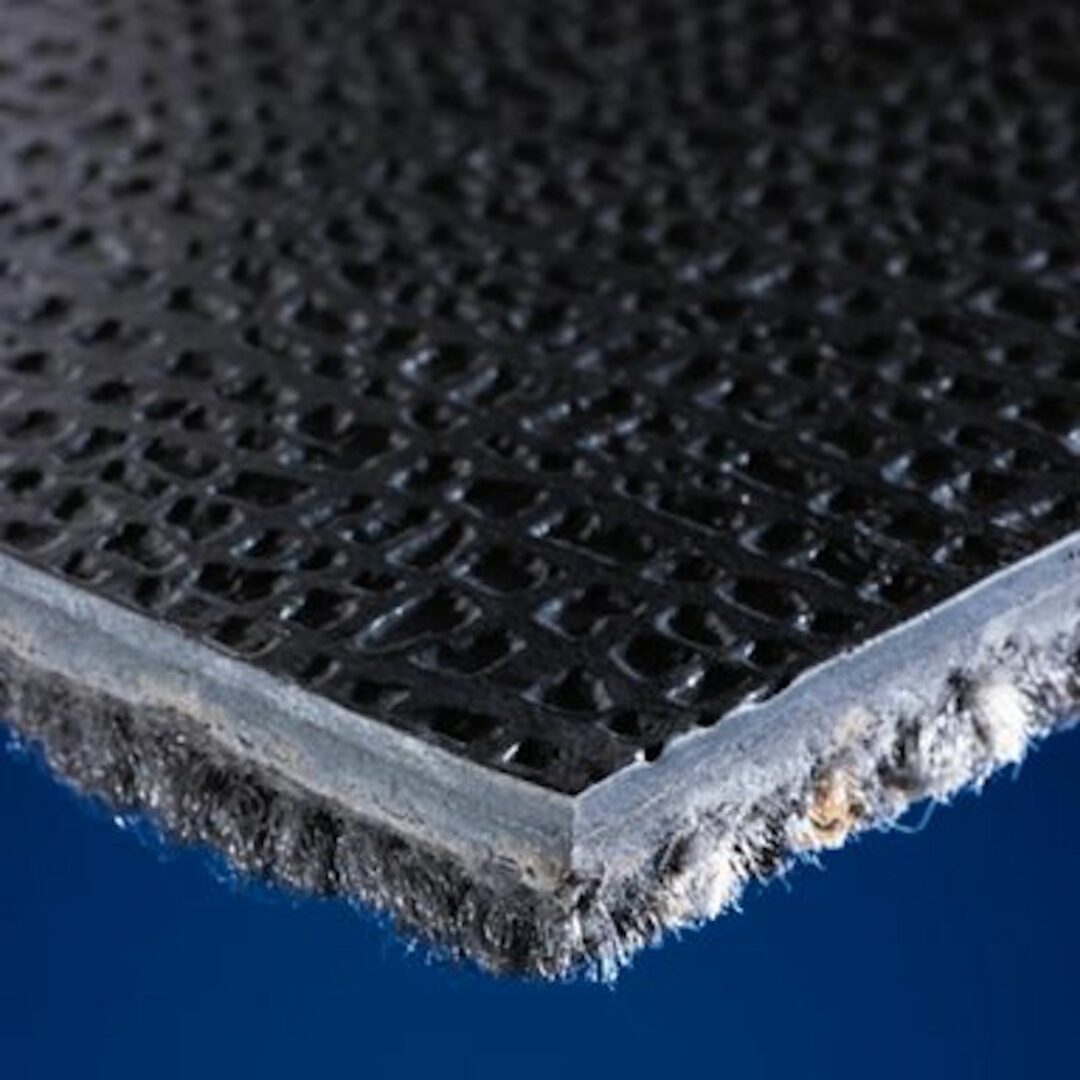

Anderson began his new company by focusing heavily on the new technological process for making carpet tiles called fusion bonding. The process implanted yarn directly into a piece of backing material without using needles or looms. Anderson changed the name of his company to Interface Flooring Systems in 1982. The following year, Interface became a publicly traded corporation. Maintaining an emphasis on carpet tiles while expanding into other related product lines, Interface became by the late 1980s the fourth largest commercial carpet maker in the United States, and the second largest carpet tile maker in the world.

Carpet making is inherently unfriendly to the environment. Most carpet and carpet tiles are made from nylon, refined from pools of petroleum; two known carcinogens, fiberglass and polyvinyl chloride (PVC), are chief components in carpet-backing materials; the dyes used to color carpets are flushed into the region’s streams. When carpet has outlived its usefulness, it generally is sent to landfills. By the late 1980s virtually indestructible old carpets made up a growing part of the nation’s waste. “For the first twenty-one years of the company’s existence, I never gave one thought to what we were taking from the earth or doing to it, except to be sure we were in compliance and keeping ourselves 'clean’ in a regulatory sense,” Anderson recalled. In 1994 an employee gave him a copy of Paul Hawken’s The Ecology of Commerce. Hawken, an entrepreneur who founded successful firms in natural foods and high-quality tools, had become a leader in the movement for sustainable development. Hawken argued that in order to maintain the planet’s ability to sustain life, per capita use of resources and energy had to be reduced by 80 percent. As the extinction of species accelerated and human waste began to choke the planet, Hawken characterized the declining prospects for life as “the death of birth.”

Courtesy of Interface

The book changed Anderson’s life. “Think of it, 'the death of birth,'” he mused later; “that phrase was a spear in my chest.” After reading the book, he convened a meeting of Interface managers and began the process of changing the corporate culture. Anderson became one of the leading spokesmen for sustainable development over the next decade. Within four years the company had reduced emissions by 30 percent and solid waste by half. In the midst of what Anderson termed a “revolution in this company,” sustainability seemed good for business as well as good for the environment, as the company’s stock price and profits rose after the initial cost of conversion. Recognition followed such accomplishments. Anderson received the Millennium Award from Global Green in 1996. In 1997 U.S. president Bill Clinton named him cochair of the President’s Council on Sustainable Development. He received the prestigious George and Cynthia Mitchell International Prize for Sustainable Development in 2001, the first corporate chief executive officer to be so honored.

Anderson’s gospel of sustainability helped carry Interface into the twenty-first century. Still, progress was painstakingly slow. He committed Interface to the eventual production of 100 percent recyclable products, with no waste. But in the early twenty-first century Interface still used enormous amounts of unrecyclable nylon. The technology to fully implement sustainability did not yet exist. Interface continued to provide industry leadership in this direction, however, and Anderson continued to evangelize for sustainable development. He expressed little enthusiasm for government mandates, however, preferring to rely on customers who increasingly demanded environmentally sound products. Anderson had managed to create a rare institution—a profitable corporation that also appeared dedicated to values beyond the profit motive.

Georgia and the South created a textile industry in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries through the sustained efforts of boosters and entrepreneurs like the Callaway family, who created Callaway Mills, Anderson’s first employer. Georgia’s old textile industry suffered in the twentieth century, but it proved capable of producing dynamic new spin-off industries. Industrialization and a growing market economy brought new environmental dangers to Georgia and the South. But the same forces also helped produce potential solutions.