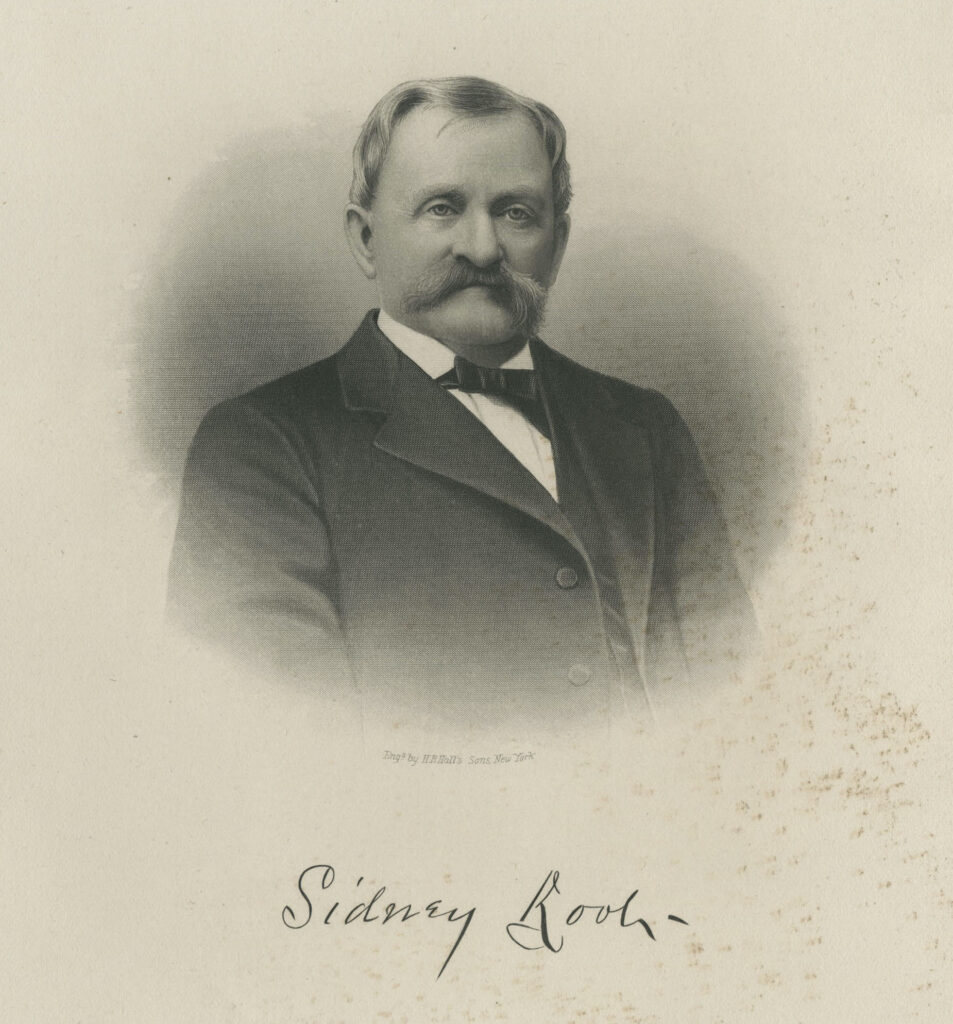

One of early Atlanta’s most prominent merchants, Sidney Root played several high-stakes roles in service to the Confederacy during the Civil War (1861-65) and focused the attention of the international business community on Atlanta.

His public life also included developing greenspace in Atlanta and pioneering forest conservation in Georgia, as well as advocating higher education for African Americans and religious training for both Blacks and whites. His son John Wellborn Root was a significant nineteenth-century architect.

Early Life

Root was born on March 11, 1824, in Montague, Massachusetts, to Eliza Carpenter and Salmon Root. His parents nurtured his flare for politics and religion. According to Root’s unpublished memoir, “Memorandum of My Life,” his father, a Whig, knew and revered statesman Daniel Webster, while his mother, a Jacksonian Democrat, was a devout Congregationalist. As an adult, Root became a Baptist. In 1861 he published Primary Bible Questions for Young Children, and the popular booklet eventually sold around 20,000 copies.

Root’s farming family moved to Craftsbury, Vermont, when he was eleven. After a few years on the farm and three more working with a watchmaker in Burlington, the youth yearned for bigger opportunities. Root left Vermont for Georgia in 1843 at the invitation of his brother-in-law, William A. Rawson. Rawson employed Root as a general-store clerk in the then-burgeoning west Georgia town of Lumpkin. In time Rawson’s store became Rawson and Root, and in 1855 the business became Root’s alone.

In 1849 Root married Mary Harvey Clark, and the couple had three children: John, Florence, and Walter. Both sons became architects. The marriage transformed Root into a slaveholder when the couple received three enslaved laborers from the bride’s parents as a wedding present.

Antebellum Era

Seeking greater opportunity, Root established a partnership in Atlanta with a merchant, John N. Beach, in 1857, and the following year he moved his family to Atlanta from Lumpkin.

The primary interest of Beach and Root was dry goods. The partners built Atlanta’s first three-story iron fronts, located on Whitehall and Pryor streets. (Cast-iron storefronts were valued by merchants in the mid-to-late nineteenth century for their distinctive appearance and their ability to support more weight than the same volume of wood could.) Their activities eventually broadened into cotton and banking. In a few short years Beach and Root became the most lucrative commercial firm in Atlanta.

Civil War Era

Though suspected of harboring Unionist sentiments, Root publicly solidified his allegiance to the South by enlisting at age thirty-seven in the Minute Men of Fulton County. He was also among those who accompanied Confederate president Jefferson Davis from Ringgold, Georgia, to Montgomery, Alabama, for his inauguration in February 1861.

President Davis immediately asked Root to supply the Southern army and public with goods imported from Europe, thus tapping Beach and Root for blockade-running, or bringing goods secretly past the Union ships guarding Southern ports. Root accepted the task, establishing an office and warehouse in the port city of Charleston, South Carolina. He dispatched his partner, Beach, to open an office in Liverpool, England. The firm later opened additional offices in Le Havre, France, and Wilmington, North Carolina. By the war’s end Beach and Root had added about twenty British-built steamers to their fleet.

Atlanta’s mayor, James M. Calhoun, turned Root’s official wartime business with Europe to the city’s advantage, asking Root to solicit direct trade between European firms and Atlanta. Root formed a “board of direct trade” among the city’s merchants; this board, which sent agents to manufacturing cities in Europe, would eventually become the Atlanta Chamber of Commerce. Atlanta’s first industries began forming as a result of the board of trade, including a lard oil factory and Sugar Creek Paper Mills. Atlanta’s international reputation for business thus became Root’s greatest lasting contribution. In the process, Beach and Root made millions of dollars.

In 1864 Root revived a controversial plan, first presented by Confederate major general Patrick Cleburne in 1863, for recruiting enslaved men into the Confederate army. In return, they would be freed. Although top officials, including President Davis, had initially dismissed the idea, Root argued that bringing enslaved men into the army was the only hope for the Confederacy, given the significantly higher number of troops in the Union army. Root also suggested that emancipating those enslaved might result in aid from England and France.

Davis dispatched Root to meet with Confederate general Robert E. Lee, who assented to the plan. With Davis and Lee now favoring emancipation in exchange for military service by enslaved African Americans, a storm ensued in the Southern newspapers, and the media battle raged for the rest of the war. Meanwhile, major battlefield losses continued to pile up, including the fall of Atlanta in September 1864. Davis asked Root to promote the emancipation plan in Europe as a last-ditch effort to convince leaders there to give private aid to the Confederacy.

In late 1864 Root ran the blockade and proceeded to London. There he discussed the Confederacy’s emancipation plans with the earl of Derby, who enthusiastically quoted Root’s report in a speech to the House of Lords. Later, in Paris, France, Emperor Louis-Napoleon (Napoleon III) also received Root. Both of these discussions came in advance of a visit by Davis’s official emissary, Duncan Kenner, of Louisiana. Root shortened his visit because of the “Confederate disasters at home.” He left Paris in early March 1865 and headed to the Bahamas (a major safe harbor for his blockade-runners), arriving around May 1 in Nassau. There he sought out the American consul and swore his allegiance to the United States. He then traveled to Halifax, Nova Scotia, before returning home. Later that year Root published the nonpolitical notes of his time in London, Exotic Leaves, Gathered by a Wanderer, one of America’s earliest European travelogues.

Postbellum Era

The Civil War had not ruined Root, but his fortunes were severely depleted. Aside from his home, which, during the siege of Atlanta, had been occupied by the Union army, the war had laid waste to all the rest of Root’s properties in the city. Federal marshals arrested Root and imprisoned him for three weeks in Augusta on the charge of possessing Confederate property. After Root demonstrated that he owned his properties, he was released.

The Root family moved to New York City in 1866, mainly for the educational opportunities available there for their children. In 1875 a group of thirteen freedpeople living in the city came to him and requested that he lead their fledgling church mission. Root accepted, on the condition that the members admit his social superiority. He began preaching for them and helped to organize the Mount Olivet Baptist Church, which had 1,000 members by the 1890s.

The Roots returned to Atlanta in 1878, primarily because their daughter had married and moved there. Root devoted the rest of his life to religious and commercial boosterism. He served as a trustee for the Atlanta Baptist Seminary (later Morehouse College) and Spelman Seminary (later Spelman College), but only on condition of social, gender, and racial segregation. Even so, he brought significant resources to the schools, especially to Spelman, which received $100,000 from John D. Rockefeller at Root’s urging.

Other charitable causes in Atlanta aroused his interest as well. Root became the director of the International Cotton Exposition of 1881, and in 1883 he began serving as park commissioner for the city. In that capacity he persuaded Lemuel Grant to establish Grant Park and exerted a significant influence on its design.

During this time Root also traveled around the country to attend the meetings of newly formed forestry associations. At his bidding, the Georgia General Assembly issued an invitation to the Southern Forestry Congress to hold its annual meeting in Atlanta, which it did in 1888. The state parks of north Georgia owe their existence in part to the groundwork laid during that meeting.

Root also sought to stop the practice of leasing state prisoners to private businesses, a system instituted by provisional governor Thomas Ruger in 1868, and he orchestrated the 1886 National Prison Congress in Atlanta, over which former U.S. president Rutherford Hayes presided. While reform did not come immediately, the convict lease system was ended by legislative decree in 1908.

Root died on February 13, 1897, at his daughter’s house. His death notice appeared in the Atlanta Constitution that same evening, and his obituary in the New York Times began by proclaiming that he was “the closest personal friend of Jefferson Davis after the war.”