The county unit system was established in 1917 when the Georgia legislature, overwhelmingly dominated by the Democratic Party, passed the Neill Primary Act. This act formalized what had operated as an informal system, instituted in Georgia in 1898, of allotting votes by county in party primary elections. (A primary election is held before a general election in order to determine each political party’s candidates for the general election.) The county unit system continued to be used in Democratic primaries for statewide office and selected U.S. House districts until the early 1960s.

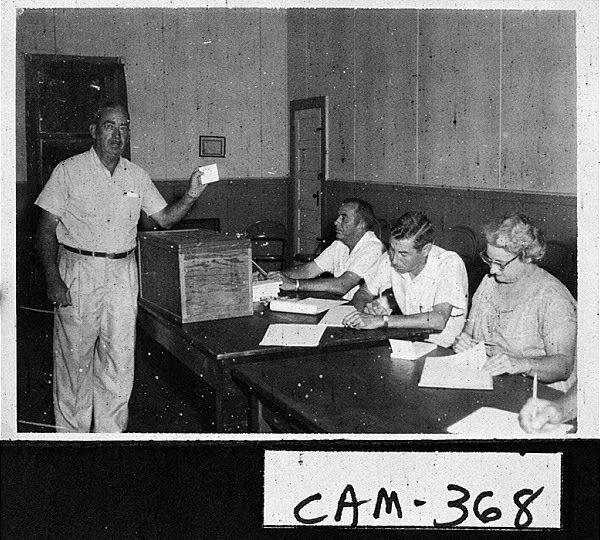

Courtesy of Georgia Archives.

In effect, the system of allotting votes by county, with little regard for population differences, allowed rural counties to control Georgia elections by minimizing the impact of the growing urban centers, particularly Atlanta. All 159 counties were classified according to population into one of three categories: urban, town, and rural. Urban counties were the 8 most populous; town counties were the next 30 in population size; and rural counties constituted the remaining 121. Based upon this classification, each county received unit votes in statewide primaries. The urban counties received six unit votes each, the town counties received four unit votes each, and the rural counties received two unit votes each.

Given that Georgia voters were almost entirely Democratic during the first half of the twentieth century, elections were more often decided at the primary stage than in the general election. In the Democratic primary, candidates concerned themselves more with winning counties than with winning the popular vote and thus spent far more time campaigning in rural areas and small towns than in the state’s major cities. With a statewide total of 410 unit votes, a candidate needed 206 to win the party’s nomination, despite the outcome of the popular vote. If a candidate won a plurality of the popular vote in a county, then he received the entire unit vote from that county, meaning that the votes of rural counties could easily equal, and effectively negate, the votes of urban counties. In many elections, candidates who received the majority of popular votes were defeated by candidates who carried the most county unit votes.

Census data from 1960 illustrate the inequities of the county unit system. Although the rural counties accounted for only 32 percent of the state population by that year, they controlled 59 percent of the total unit vote. For example, the state’s three least populous counties, Echols, Glascock, and Quitman, had a combined population of 6,980, while Fulton County, the most populous, had a population of 556,326. Collectively, the three smallest counties had a unit vote that equaled the unit vote of Fulton. The significance of this system was that the rural counties enjoyed a control of statewide elections that was out of proportion to their size. As a result, rural votes served to protect such policies as legal segregation and other aspects of white supremacy by diluting the influence of more liberal urban voters and of Black voters, who were concentrated in Georgia cities.

Constitutional challenges to this system and others like it elsewhere in the nation were made several times in the 1940s and 1950s. The U.S. Supreme Court refused, however, to take on such cases because the court considered the dispute to be an apportionment issue that should be resolved within individual states. Finally, in March 1962 the Supreme Court considered a Tennessee-based case, Baker v. Carr, in which it ruled that all citizens’ votes should have equal weight and that the county unit system violated the principle of “one man, one vote.”

At the same time, a historic lawsuit, Gray v. Sanders, was filed in Georgia. An Atlanta resident, James O’Hear Sanders, sued James Gray, the head of the state Democratic Party, and other officials on the grounds that Sanders’s vote was worth less than that of Georgians who lived elsewhere. Judge Griffin Bell headed a judicial panel that ruled in April 1962 that the system was indeed invalid in its present form and must be redesigned before the next Democratic primary, which was scheduled for September. The panel declared that every vote was to be given equal weight regardless of where in the state a voter lived.

Photograph from the National Archives and Records Administration

This, according to Jimmy Carter, was “one of the most momentous political decisions of the century in Georgia,” and his book Turning Point: A Candidate, a State, and a Nation Come of Age (1992) describes the impact of eliminating the county unit system. After the county vote system was abolished, Carl Sanders won the Democratic gubernatorial primary in fall 1962 and was later elected governor. He was the first governor from an urban county in Georgia since the 1920s.