In 1786 an act of the state legislature set aside the western lands of Washington County to create Greene County and its seat, Greenesborough (later Greenesboro, then Greensboro), which was incorporated in 1803.

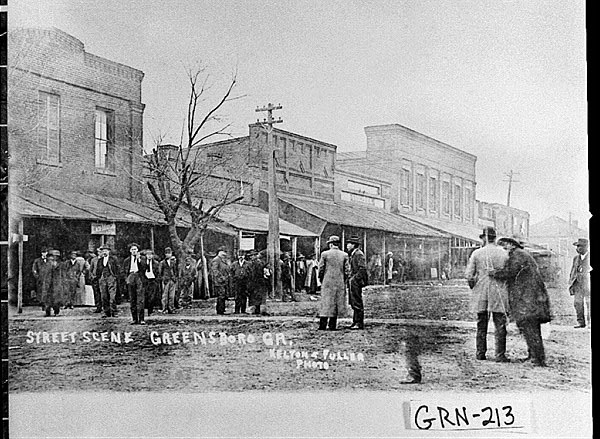

Taking its name from Nathanael Greene, a general in the Revolutionary War (1775-83), Greensboro served as the commercial center of one of Georgia’s most important cotton-producing counties. The city’s history illustrates the struggle, common to many small towns in the rural South, to emerge from the shadow of a cash-crop monoculture.

Located between the Ogeechee and Oconee rivers in Georgia’s formerly rich cotton belt, Greensboro lies at the heart of Greene County, halfway between Atlanta and Augusta. The Creek Indians prized this region for its abundant game. The Georgia legislature created the county in hopes of attracting white settlers to the region and dislodging the Creeks. Although the state attempted to maintain a facade of legality in taking Indian lands, tensions ran high between white newcomers and Native Americans. In 1787 Indians attacked Greensboro, burning homes and killing residents. Despite these and other difficulties of frontier life, Greensboro and Greene County grew rapidly. By 1810 the county as a whole claimed 12,000 residents, half of whom were enslaved people. A decade later enslaved workers composed a majority of the population.

Cotton Is King

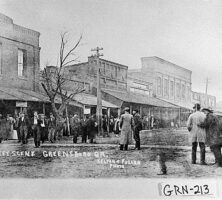

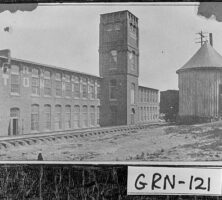

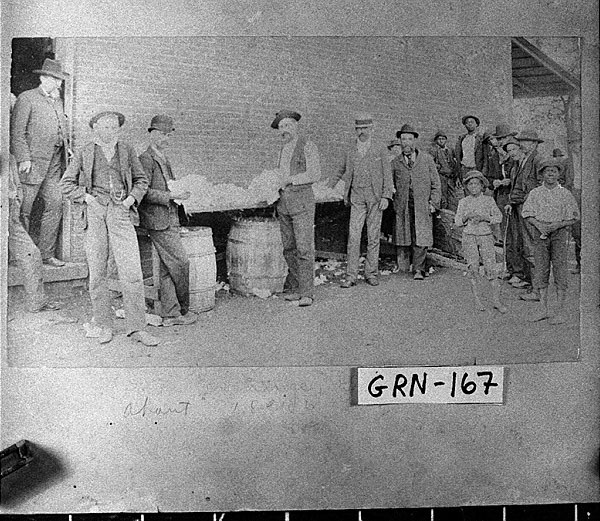

The phenomenal rise of the cotton economy facilitated the growth of Greensboro as the commercial center of Greene County. Fifty years after its founding, Greene became Georgia’s largest cotton-producing county. In 1838, responding to the need to transport the region’s ever-growing crop, the Georgia Railroad reached Greensboro, cementing the city’s status as the county’s commercial center. By 1854 the town had its own cotton mill, the Greenesboro Manufacturing Company. The merchant class that profited from this commerce became the town’s elite.

Although cotton made a few men extremely wealthy and underwrote the proliferation of stores, banks, and civic buildings in Greensboro, it also created an underclass in the form of enslaved Blacks and poor whites. Despite the social and economic system that kept a majority of the county’s citizens enslaved and impoverished, there was little question of which side county leaders would support in the secession crisis leading to the Civil War (1861-65). All three of Greene County’s representatives to the Georgia Secession Convention voted to secede, and Greensboro men organized the Greene Rifles to fight for the South. Of the men that Greene County sent to war, one-third would not return and another third would come back maimed or wounded. A portion of Union general William T. Sherman’s troops briefly occupied Greensboro in November 1864 in a diversionary tactic meant to convince the Confederates that the Union troops were headed for Augusta, not Savannah, on their march to the sea.

Aftermath of War

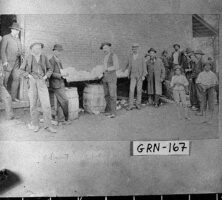

The end of the Civil War unleashed pent-up social forces in Greensboro and Greene County. Many newly freed African Americans, looking for lost relatives or for a better life in the city, migrated to Greensboro and formed a community known as Canaan, which became a center of Black activism in the following years. With the votes of the newly enfranchised African Americans, Greene County elected a slate of Republican candidates in 1868. But whites moved quickly to return African Americas to their subordinate civic and socioeconomic positions. Through a series of beatings, home burnings, and murders, the Ku Klux Klan thwarted the promise of Reconstruction. Greensboro’s Black community formed an equal-rights association and a militia, but despite their relative militancy, excellent leadership, and strong solidarity, they were unable to stem the tide. Greene County was officially “redeemed” in 1874.

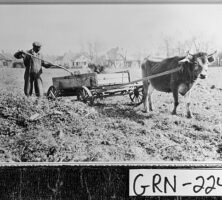

Return to Cotton

Despite a short-lived attempt to turn toward increased food production, Greene County quickly returned to its dependence on cotton and suffered the attendant consequences. With the demise of the old plantation system, sharecropping and tenancy rose to take its place. The elite of Greensboro prospered, though. Many who formerly had only sold goods became moneylenders in the furnishing system, which arose after the demise of the old cotton-factory system. The proliferation of sharecropping contracts also led to a rise in the number of prosperous lawyers in town.

Despite a brief flirtation with Populism in the 1890s, the status quo held in Greensboro into the 1930s. The fortunes of the town and the surrounding area rose and fell with the vagaries of the international cotton market. As the boll weevil began to devastate much of Georgia’s crop, Greene County turned more heavily toward cotton after developing a reputation for being “weevil proof.” Prosperity before World War I (1917-18) led to a proliferation of automobiles and other luxury consumer goods in Greensboro and even allowed many tenants to become landowners. But in 1922 the weevil finally devastated Greene County’s cotton production, ending the boom time in Greensboro and undermining land values. Both of the city’s banks closed, the Georgia Railroad stopped making scheduled stops, and Greensboro languished until the innovations of the New Deal.

The New Deal Arrives

Greensboro benefited greatly from the try-anything attitude of the New Deal years. The offices of the Greene County Civilian Conservation Corps and Works Progress Administration were located in the city. The roads to and from Greensboro became more heavily traveled by farmers looking to pick up checks from the Agricultural Adjustment Administration or to get information on the latest programs being offered by the federal government. The town’s merchants undoubtedly weathered the Great Depression much better because of the money pumped into the local economy. As in the rest of the South, the federal largesse was not distributed equally. Despite Greene County’s majority Black population, relief mostly benefited its white residents, with those in Greensboro disproportionately assisted.

World War II and Beyond

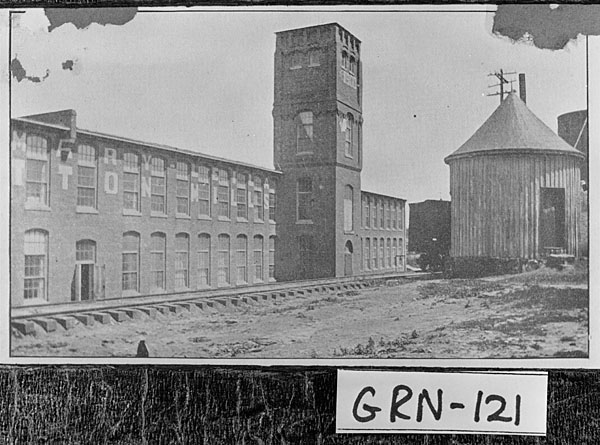

Whatever temporary relief New Deal programs may have provided, Greensboro and Greene County could not truly prosper until there were enough industrial jobs to absorb the surplus agricultural population. Following the lead of the rest of the South in the early twentieth century, the county attempted to entice industry to the area through its Greene County Development Company. Greensboro recorded its first such success in 1899, when the Mary-Leila Cotton Mill opened. World War II (1941-45) proved a boon to the cotton mill, though it would achieve a certain amount of adverse notoriety when its workers went on strike for higher wages in 1941.

The number of farms and farm workers continued to decline in the aftermath of the war. Greensboro struggled to provide enough jobs for those who no longer wanted to farm or, having been pushed off the land, no longer could. In 1974 the town could claim some 918 manufacturing jobs (most of these in the garment industry) at a time when its population was 2,583 and that of the county as a whole stood at roughly 10,000. Today Greensboro and the surrounding area lag behind state and national averages in such areas as poverty and education. The industrial jobs offered in years past by large-scale operations, which could often provide an entree for workers into the middle class, have largely evaporated, and the city still struggles to attract much-needed jobs to the area. Greensboro’s largest employers provide service-sector jobs catering to the well-to-do who come to live or vacation on the shores of Lake Oconee.

According to the 2020 U.S. census, Greensboro’s population was 3,648. Its lively and historic downtown area offers a variety of shops and services, as well as historic tours. Several museums, including the Greene County Historic Museum and the Calvin Barber Museum and African-American Resource Center, are also located in Greensboro.