Thomasville, the county seat of Thomas County, is located in southwest Georgia’s wiregrass region. The city is forty miles north of Tallahassee, Florida, and fifty-four miles south of Albany.

Originally the home of the Apalachee Indians and the Lower Creek Indians, the area was first visited by Europeans when Hernando de Soto’s Spanish expedition passed through in 1539-40. After the American Revolution (1775-83) it became a part of Georgia and the United States.

Land-hungry Americans rushed into the area after the Creek Indian removal, and in 1818 the Georgia legislature began creating counties to accommodate their needs. In 1825 Decatur County representative Thomas J. Johnson introduced the bill creating Thomas County. Both the county and Thomasville, established the following year, were named for Johnson’s relative General Jett Thomas, an Indian fighter during the War of 1812 and the builder of the antebellum state capitol in Milledgeville and Franklin College, the first permanent structure at the University of Georgia in Athens.

Major boundary changes came in 1858, when Brooks County was created, and in 1905, when Grady County was carved out of Thomas and adjacent counties. Despite sporadic Indian conflicts, the county grew between 1830 and 1860 from a population of 3,299 to 10,766. A permanent courthouse, still in use, was built in 1858. The architect was a young Englishman named John Wind. Poor roads hindered transportation, and the Ochlockonee River could not be navigated by commercial ships, but in 1861 the Atlantic and Gulf Railroad connected Thomasville with Savannah.

Thomasville became the center of an important antebellum agricultural kingdom that produced large amounts of cotton (shipped through nearby Florida ports), corn, sugarcane, and sweet potatoes. Farm animals, especially range cattle, were significant. Enslaved people were the primary labor source. There were also numerous white yeoman farmers. Planters, even though they were a minority, controlled economic, social, and political life. The enslaved population increased rapidly, and by 1860 the county had 6,244 in bondage, 34 free African Americans, and 4,488 whites.

Antebellum Thomasville was overwhelmingly Protestant. Its major churches were the Methodist, Presbyterian, and Baptist, both missionary and primitive. Whites admitted enslaved congregants and supervised their religious services. Education before the Civil War did not include any religious instruction to Blacks and depended mainly on private and church schools or academies. The Methodist-affiliated Fletcher Institute, which opened in 1848, was Thomasville’s most important educational institution at that time.

In politics the majority Democrats usually prevailed over the Whigs, a strong minority. While both parties supported the institution of slavery, and Thomasvillians took the southern position in the nation’s growing sectional quarrels over slavery, Thomasville reluctantly left the Union when Georgia seceded in 1861. After the Confederate States of America was founded, however, Thomasville became a loyal member of the new nation. No battles took place in Thomas County, but Thomasville and the county furnished military personnel who fought on every battlefield. Ultimately, approximately 1,500 men served in Confederate and state militia units. Thomasville was a haven for many refugees fleeing from combat zones and in December 1864 served briefly as a prisoner of war camp for 5,000 Union soldiers. Thomasville’s railroad was an important shipping point for soldiers and agricultural produce. On May 9, 1865, Union forces entered Thomasville and received the surrender of Confederate forces and supplies.

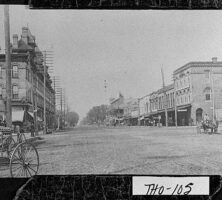

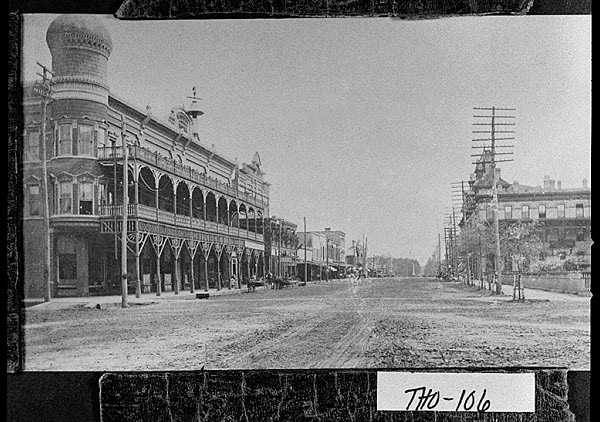

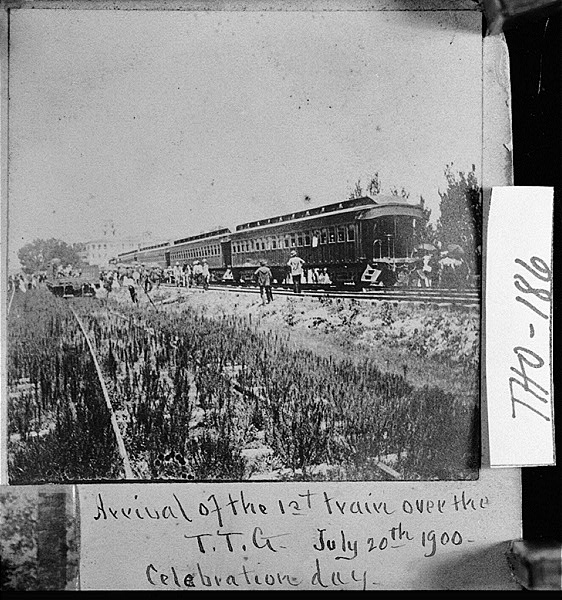

The painful process of Reconstruction was made easier in Thomasville by the lack of wartime destruction, the absence of deep-seated hatred of the North, and a quick recovery that saw improved roads, the rapid expansion of railroads, and the beginnings of a small city. By the 1880s it was a magnet for wealthy northerners (many of them from Cleveland, Ohio) who built or bought homes in town and plantations in the county, turning Thomasville and the county into a resort area.

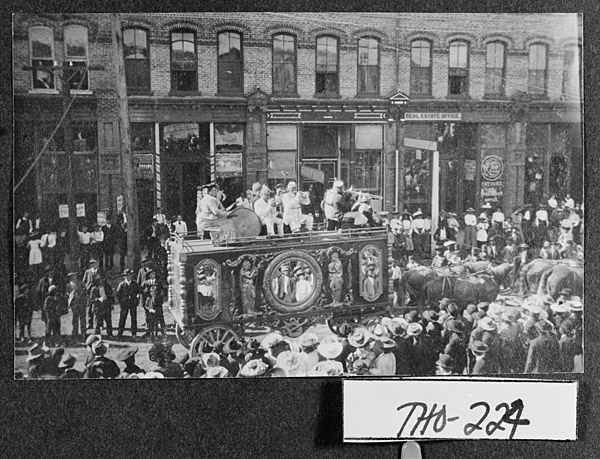

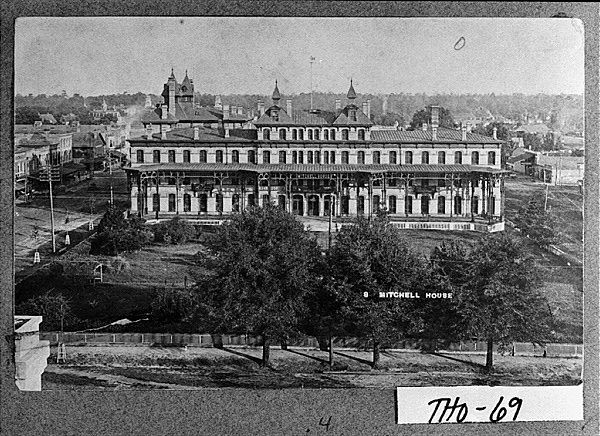

In the 1880s such luxury hotels as the Mitchell House and Piney Woods rose on Broad Street, and across the city many smaller hotels and boardinghouses catered to the less affluent. Until about 1910 guests came yearly for a “season” devoted to socializing, hunting, and fishing, and many of their descendants continued to visit Thomasville every year. Present-day Thomasville is the unofficial capital of an area of hunting plantations that stretches north to Albany and south to Leon and Wakulla counties in Florida.

Beginning in the late 1870s the pine timber industry became important. Agriculture has adapted to modern techniques and, like timber, remains basic to the county’s economy. Since the 1920s the John D. Archbold Memorial Hospital (later, Archbold Medical Center) has been an important medical center, and the Flowers Baking Company ranks among the national leaders in the bread industry.

Thomasville has two institutions of higher education. Thomas University is a small, private institution located on the grounds of what was once Birdwood Plantation, the winter home of W. Cameron Forbes, U.S. ambassador to Japan and governor general of the Philippines during the early twentieth century. In 2004 the university had an enrollment of more than 700 students. Southwest Georgia Technical College (later Southern Regional Technical College), operated by the Technical College System of Georgia, opened in the city in 1947.

Well-known natives of Thomasville include educator Selena Sloan Butler; Henry O. Flipper, the first Black graduate of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point in New York; Georgia governor Thomas Hardwick; writer Bailey White; and actors Scott Wilson and Joanne Woodward.

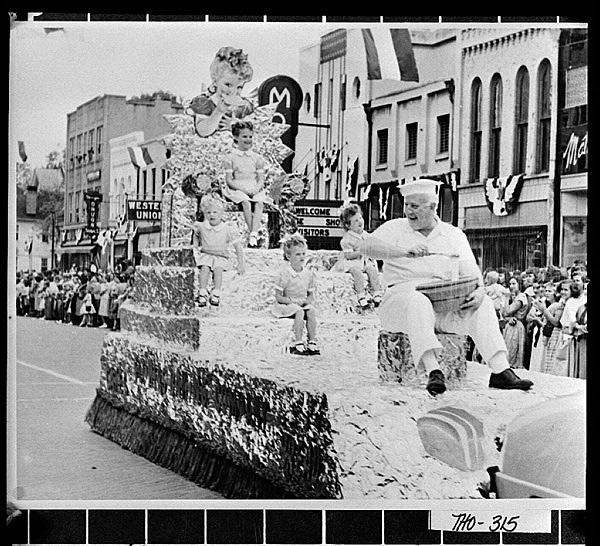

Thomasville, called “the Rose City” because of its many colorful rose gardens, added an annual rose show in 1922 and a rose show parade in 1948. According to the U.S. census, the city’s population in 2020 was 18,881.