Note from the Editors: In January 2013 Georgia Health Sciences University (GHSU) merged with Augusta State University to form Georgia Regents University (later Augusta University). This article chronicles the history of GHSU from its founding until the time of the merger.

Georgia Health Sciences University (GHSU), located in Augusta, is the state’s public university for health sciences. From 1833 until 2011, it was known as the Medical College of Georgia. Accredited by the Commission on Colleges of the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools, the university had in 2010 approximately 2,500 students enrolled in five colleges: medicine, nursing, dentistry, graduate studies, and allied health sciences. The mission of the institution is to “discover, disseminate, and apply knowledge to improve health and reduce the burden of illness on society.”

Most of the school’s students are from Georgia; more than a quarter are minorities, and women make up more than two-thirds of the student body. GHSU offers advanced certificates as well as degrees ranging from baccalaureate to doctoral. The college operates additional clinical campuses in Albany and Savannah, as well as satellite nursing campuses in Athens and Columbus. In 2010 the school joined with the University of Georgia (UGA) to form a partnership, which resulted two years later in the opening of a new medical school campus in Athens.

Early History

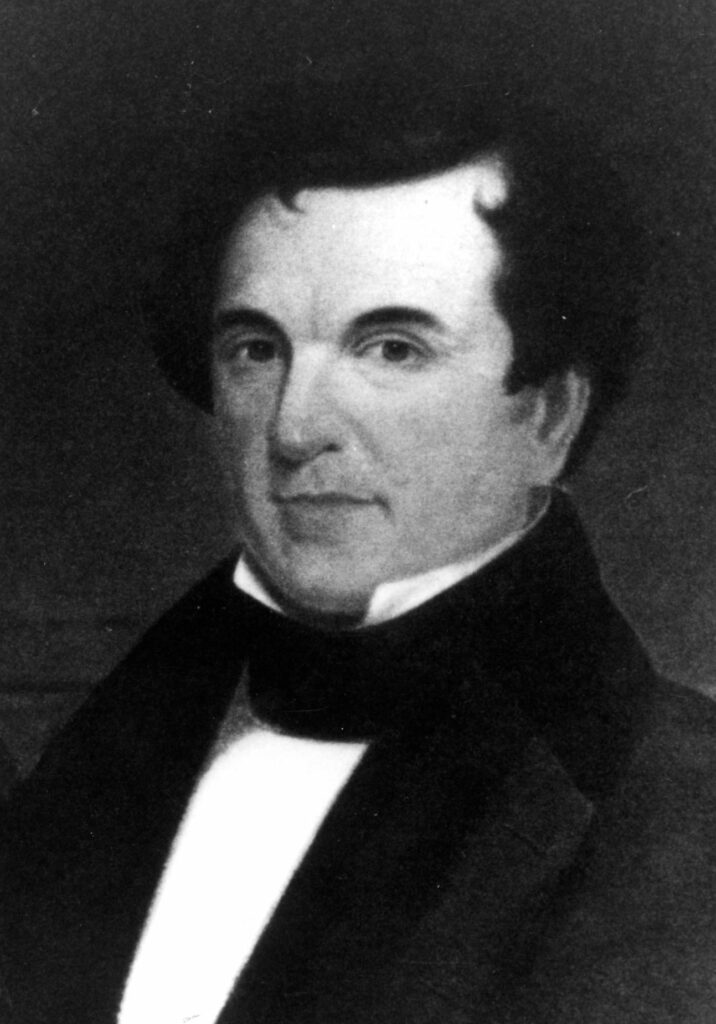

The Medical Academy of Georgia was founded at the instigation of Augusta physician Milton M. Antony on December 20, 1828, when Georgia governor John Forsyth signed the school’s charter. The school was given authority to run a one-year program that awarded a bachelor of medicine degree on its completion. The academy officially opened on October 1, 1829, with three faculty members (Antony, Ignatius P. Garvin, and Lewis DeSaussure Ford) and seven students, in the facilities of the Augusta city hospital.

Courtesy of Historical Collections and Archives, Robert B. Greenblatt, M.D. Library, Georgia Health Sciences University

Since the academy’s program was limited to one year, the board of trustees investigated the possibility of transferring this credit to other nearby schools. It became clear that transfers would be difficult, so the trustees petitioned the state legislature to extend the school’s charter to allow them to grant medical doctorates. The legislature approved this alteration in December 1829, and the name of the institution was changed to the Medical Institute of the State of Georgia. To support its expanded mission, the trustees approved doubling the size of the faculty and adding a second year of lectures. In 1832 the trustees reappointed the three existing faculty members (Garvin had been replaced with Joseph A. Eve) and added Louis A. Dugas, John Dent, and Paul F. Eve. Courses covered chemistry, anatomy and physiology, midwifery, diseases of women and children, materia medica (pharmacology), surgery, and institutes and practices of medicine.

Courtesy of Historical Collections and Archives, Robert B. Greenblatt, M.D. Library, Georgia Health Sciences University

In 1833 the institute’s name was changed to the Medical College of Georgia (MCG), and the state legislature granted funds to acquire adequate facilities. (The college’s first building was designed by prominent Georgia architect Charles B. Cluskey.) In addition, the Academy of Richmond County donated property, faculty members contributed money for a library and museum, and the city of Augusta promised to pay the college in return for medical services for the indigent. Besides this funding, MCG was a proprietary institution, dependent on tuition and fees.

Faculty members were active in the founding of what is now the Medical Association of Georgia and of the American Medical Association (AMA). Despite its leadership in these organizations, MCG’s faculty was unable to persuade other medical schools to institute a longer term of six months instead of the standard four. Ultimately, MCG found the longer term to be unsustainable, as other medical schools across the country continued to use the shorter term.

During the antebellum years, the college struggled regularly with weak finances and increasing competition (both for students and faculty) from new medical schools in Georgia, several of which opened in the 1850s. (Among these was the Atlanta Medical College, the forerunner of Emory University School of Medicine.) Yellow fever outbreaks in 1839 and 1854 delayed the beginning of those academic years, but the college continued to grow in spite of such challenges and in the 1850s awarded about fifty medical degrees annually. The library and museum were of high caliber for the era, and students received ample clinical exposure. Members of the college’s faculty were also responsible for the publication of the Southern Medical and Surgical Journal, a distinguished scholarly publication of its time.

MCG was not immune to the disruption caused by the Civil War (1861-65). Both faculty and students withdrew to offer their services in the war effort, and the class of 1861 was granted early commencement. Although it was originally hoped that the school would be able to carry on a normal 1861-62 term, this was not achieved, and the institution closed for the remaining war years. The college gathered its faculty and reopened for classes in the fall of 1865 with forty-seven students, three of them from the U.S. Army. The war had negatively affected MCG’s enrollment and financial status, and its temporary closure resulted in a significant loss of momentum.

Inclusion in the University of Georgia

In 1873 MCG agreed to be incorporated into the University of Georgia (UGA) as the Medical Department of UGA. The seal of the university and signature of the chancellor were placed on the diplomas of medical graduates, but the medical school remained otherwise independent and had little expectation of financial support. The change was intended to enhance the prestige of both institutions by associating the university with a well-established and respected medical college, and allowing the college to distinguish itself from the many newer medical schools just opening in the state. Fees were also lowered to match those at the university, resulting in an upswing in enrollment. Women began attending chemistry classes as early as 1875, but none were permitted to enroll as medical students at that time. The school’s first female M.D., Loree Florence, graduated in 1926.

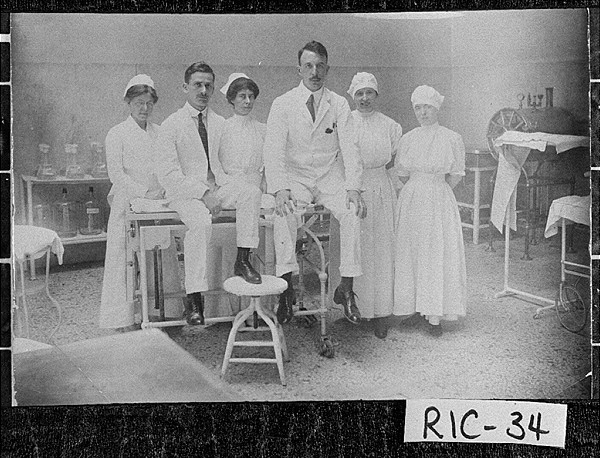

Courtesy of Historical Collections and Archives, Robert B. Greenblatt, M.D. Library, Georgia Health Sciences University

The closing years of the century were a time of difficult growth for the institution. The field of medicine was expanding more rapidly than the college, and although courses in bacteriology, histology, and pathology were added, the school was unable to make large-scale changes, such as adding separate departments for dentistry and pharmacy. The city hospital was expanded, and in 1895 a new hospital for African Americans, Lamar Hospital, was built, providing additional opportunities for clinical study.

Most important, the college made essential changes to its academic program and entry requirements. In 1893 a third term was added, the length of each term was increased to six months, and graduation and entry standards were strengthened. This was especially important as State Boards of Medical Examiners, as well as a state exam, were established in 1894. However, the college felt unprepared to support a fourth year and offered it only optionally, beginning in 1898. Despite its slow growth, the college joined the Southern Medical College Association in 1905 and received a top ranking of “A” in 1906 during the first round of medical school rankings by the Council on Medical Education and hospitals of AMA.

Courtesy of Georgia Archives.

Criticism of the initial ratings within the medical community caused the AMA to request that the Carnegie Foundation perform a new survey of medical schools, headed by Abraham Flexner. Flexner’s 1910 report was anything but complimentary of the college. He criticized its buildings as dirty, inadequately equipped, and lacking clinical facilities; declared the library to be antiquated; and described the entrance requirements as nominal. Assuming that the college would fail without the university’s support, he recommended that UGA break its ties with the medical school. Flexner’s comments galvanized the institution into action. The curriculum was rewritten to more closely resemble the recommendations of the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), and additional classes were added. The governance of the school was reorganized, and under new legislation it officially became the Medical Department of the University of Georgia in 1911. The college took over the property of the Augusta Orphan Asylum, and a new hospital, University Hospital, was completed in 1915 with the backing of the city of Augusta.

Courtesy of Historical Collections and Archives, Robert B. Greenblatt, M.D. Library, Georgia Health Sciences University

Grants from the Carnegie and Rockefeller foundations allowed the college to increase its full-time faculty following World War I (1917-18). Conflict between the newer full-time faculty and the older volunteer part-time faculty, along with the effects of a sinking economy on the school’s income, resulted in a lack of necessary growth. Disagreement as to who was responsible for costs at University Hospital caused continuous stress between the Augusta government and the college. A report by the secretary of the AAMC was highly critical of the institutional structure and recommended extensive reforms, including the appointment of a full-time dean and an executive committee more representative of full- and part-time faculty. These changes were made, but the school continued to struggle, and its problems cast the institution in a negative light at an unfortunate time.

Courtesy of Historical Collections and Archives, Robert B. Greenblatt, M.D. Library, Georgia Health Sciences University

As the Great Depression decreased state revenues, the Board of Regents of the University System of Georgia voted in 1933 to eliminate eight schools, including the Medical Department, from the university system. The school immediately campaigned to prove its importance to the state and its willingness to make any necessary changes, and within a month it had been restored to the Regents’ list for another year under the name of the University of Georgia School of Medicine, with the understanding that the college would solve some of its most troubling problems. But the school’s troubles were far from over. In 1934 the Council on Medical Education and Hospitals revoked its “A” rating, and the AAMC dropped the college from membership.

The school responded by establishing fellowships, adding new buildings and an addition to University Hospital, and persuading the Board of Regents to increase the college’s appropriations. The college was then able to persuade the council to return the hospital’s “A” rating and to rejoin the AAMC. Increasing financial support from the Board of Regents and the governor allowed the school to stabilize and eventually to increase class sizes. One victim of the crisis was the innovative School of Public Health, which ceased offering degrees in 1932 after existing for only ten years. The campus was kept busy during World War II (1941-45) as both the army and navy established training programs at the school, but the most important changes came during the following decade.

Renewed Institutional Independence

In 1950 the Board of Regents separated the Medical College of Georgia from the University of Georgia and appointed the school’s dean, G. Lombard Kelly, as the newly independent college’s president. In addition, University Hospital’s long history of accreditation struggles convinced the state to take full responsibility for providing adequate facilities for MCG in the form of its own hospital, Talmadge Hospital. In 1955 MCG took the important step of transforming its faculty to a largely full-time body and ending its dependence on part-time teaching by local doctors.

Courtesy of Historical Collections and Archives, Robert B. Greenblatt, M.D. Library, Georgia Health Sciences University

In 1956, the same year Talmadge Hospital was completed, the School of Nursing was moved from Athens to Augusta. The nursing school was founded at UGA in 1943 but continued to flourish following its transfer to MCG, and in 1974 a satellite campus in Athens was opened. A master’s in nursing program was approved in 1966, and the first doctorates in nursing were awarded in 1990. Nursing was not the only area of expansion for MCG. The college had offered master’s degrees since 1951, and in 1965 it added the School of Dentistry. In 1968 a new School of Allied Health was established from existing programs, including medical illustration, medical technology, radiology, and health information. The addition of these departments transformed MCG from a simple school of medicine into a true health sciences university.

MCG continued to expand its student body and teaching techniques. The school initiated a minority affairs program in 1969, and the following year began offering summer programs to minority students interested in medicine. Although the idea of admitting African Americans to MCG had been formally considered in 1939, it was not until 1971 that MCG first awarded degrees (two medical degrees and one B.S.N.) to Black students. In 1993 MCG began offering its first external-degree program, in medical technology. The college’s clinical facilities have also grown considerably since the opening of Talmadge Hospital in 1956, including the 1998 opening of Children’s Medical Center.

Continued Growth

In 2000 MCGHealth, Inc., a nonprofit organization, took over management of the college’s hospital and clinic facilities. The move was intended to give the hospitals greater financial flexibility, but the Board of Regents maintained ownership of the property, and MCG faculty and students continued to practice and train in the facilities. In 2010 a new administrative entity called MCG Health System, Inc., headed by incoming MCG president Ricardo Azziz, was created to oversee both MCGHealth and the Physicians Practice Group, which manages billing and insurance issues.

MCG continued to grow in the new millennium. The School of Dentistry broke ground for a new building in September 2009, and that same year MCG introduced “MCG Mobile,” a set of innovative and customizable iPhone applications for the health sciences. The applications include medical calculators, a medical glossary, and a cholesterol management algorithm.

In 2010 MCG’s Georgia School of Nursing received a federal grant of nearly $1 million to train additional nurses in acute and critical care. The school’s name changed to Georgia Health Sciences University in February 2011.

As part of an initiative to help meet Georgia’s need for physicians, GHSU and UGA formed a partnership to establish a new campus in Athens. This collaboration came to be known as the Georgia Health Sciences/University of Georgia Medical Partnership, and in January 2012 the UGA Health Sciences Campus opened on the grounds of the former Navy Supply Corps School.

GHSU is active in medical research and works to encourage cooperation between basic and clinical scientists. The school has discovery institutes in five areas: brain and behavior, cardiovascular, diabetes and obesity, immunologic, and vision science. Each institute brings together physicians and scientists to jointly study a medical topic. The five subject areas were chosen to reflect GHSU’s overall research emphases and to address common health needs of Georgia residents.