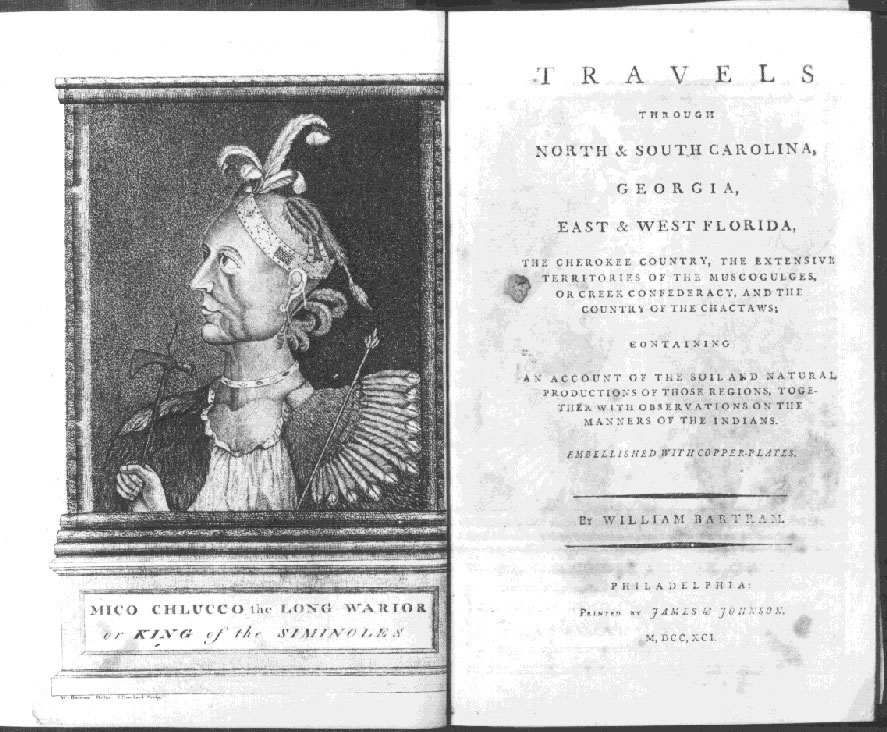

William Bartram’s 1791 book, Travels, reprinted many times, continues to fascinate American readers and attract them to the wildernesses he loved. The great explorer and diarist spent much of his time in backwoods Georgia, where he recorded matchless descriptions of the area’s flora, fauna, and Native American inhabitants.

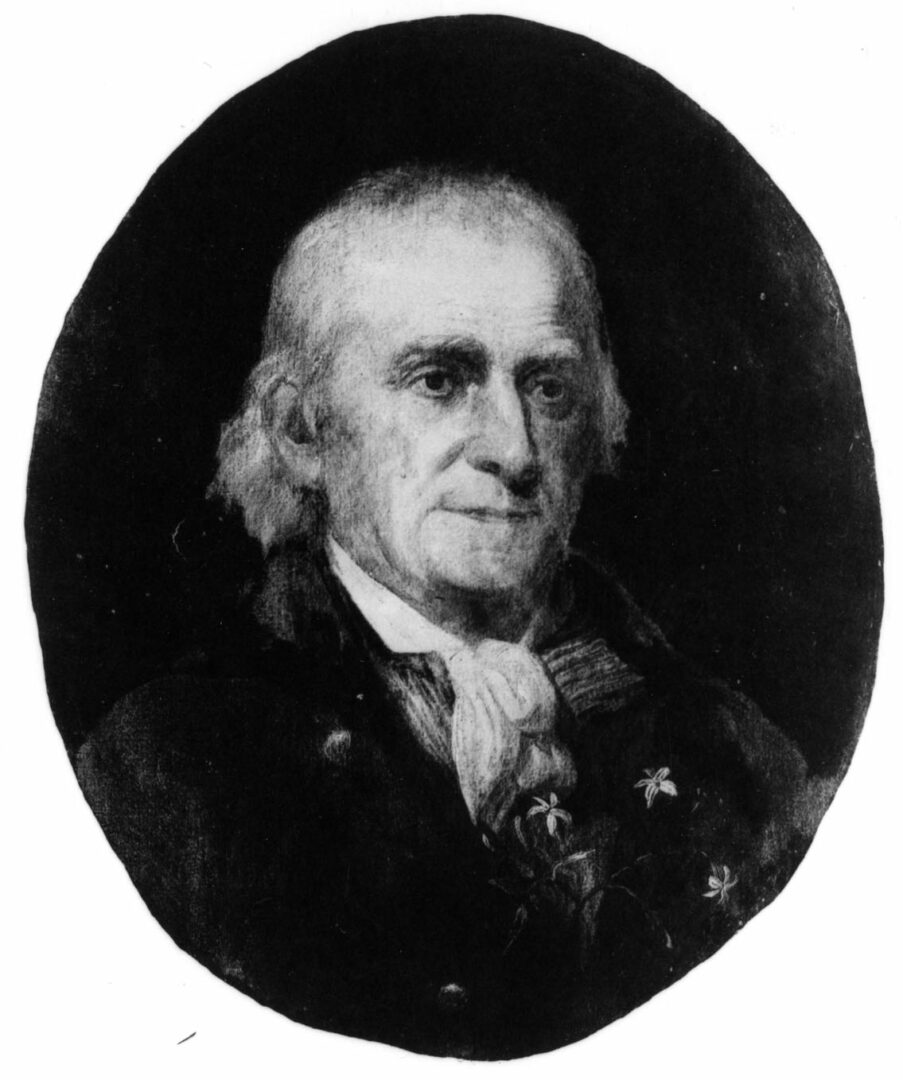

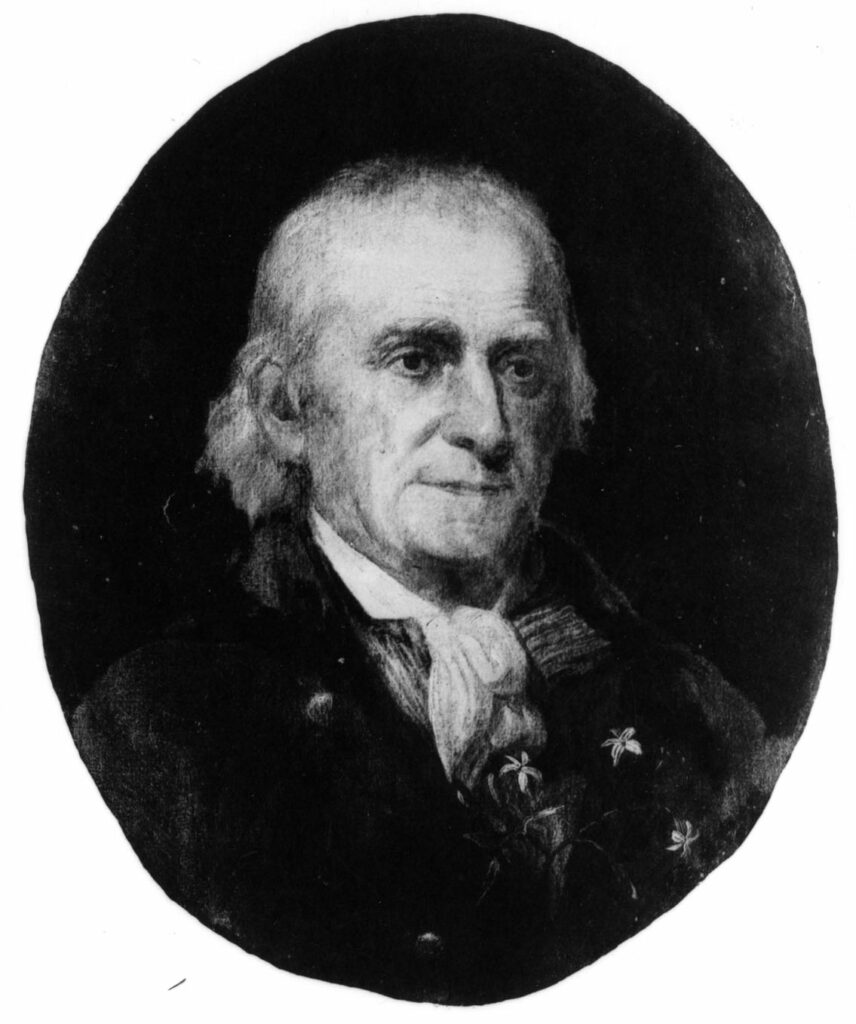

Bartram’s father, John, was his role model. John Bartram, America’s first professional botanist, loved to roam the woods in search of plants, and young “Billy” delighted in going along. Bartram and his twin sister, Elizabeth, were born at their father’s house in Kingsessing, outside Philadelphia, on April 9, 1739. As a boy Bartram developed a talent for drawing, and his father sent some of his sketches to friends in England. “Botany and drawing is his darling delight,” Bartram’s father wrote to Peter Collinson, a well-connected English naturalist and, like the Bartrams, a Quaker. He added an afterthought: “Am afraid he can’t settle to any business else.” As he grew older, Bartram tried clerking in business houses and working in printing shops, but he hated being shut indoors.

In 1765 Collinson secured a royal commission naming John Bartram as the “King’s Botanist” and authorizing him to explore Florida, newly acquired by Britain from Spain. John Bartram, now sixty-five, took his son, aged twenty-six, along with him. Starting in Charleston, South Carolina, the two visited Savannah and Augusta in Georgia, and boated up the St. Johns River in Florida. The young Bartram loved Florida and decided to try his fortune as an indigo planter on the St. Johns. His father reluctantly agreed, but the experiment turned out to be another failure. “This frolick of his hath… drove me to great straits,” his father wrote to Collinson. Bartram worked as a draftsman for the surveyor William deBrahm, helping map the Florida coast, but his vessel was wrecked in a storm. Discouraged, he returned to his father’s house, but his Florida adventure could not be counted a total loss. Collinson sent some of Bartram’s new drawings to a circle of his friends, one of whom was the wealthy plant collector John Fothergill. After another futile attempt at business, Bartram wrote to ask Fothergill to sponsor him on a botanizing expedition to Florida. Fothergill liked the idea and agreed to pay his expenses.

The great adventure that transformed the unfortunate Billy Bartram into the heroic William Bartram began when he disembarked in Charleston on March 31, 1773. His father’s Charleston connections proved helpful. John Stuart, the royal Indian superintendent, provided maps of the Indian country and informed Bartram of an important Indian congress to be held in Augusta in May. Bartram resolved to attend that meeting but spent the intervening time investigating plant life along the Georgia coast during the pleasant spring season. Bartram visited James Wright, the royal governor, in Savannah and enjoyed the hospitality of “the genteel and polite ladies and gentlemen” of Midway and Sunbury. He especially liked Lachlan McIntosh and his family and spent several days with them. His descriptions of the Altamaha River region would later inspire European poets.

Bartram’s notes of the Augusta Indian congress offer the best description of events, because the official minutes of the meeting have been lost. The Cherokee chiefs agreed to give up a huge tract of land in exchange for the cancellation of the debts they owed to traders. The Creek leaders, who claimed a portion of the same territory and who were not in debt, heaped scorn on the Cherokees. Even though the Creek elders were persuaded to sign the treaty, young warriors deeply resented the loss of their hunting grounds. Bartram accompanied the surveying party that marked the boundaries of the new cession and recorded his delight in all he saw.

Events determined the course of Bartram’s travels. The Indian conference had drawn him to the Georgia backcountry, and an outbreak of Indian hostilities thwarted his plan of touring the Indian country. He returned to the Georgia coast, and in the spring he retreated to the comparative safety of Florida. He accompanied a party of traders in the employ of James Spalding to Indian villages. Cowkeeper, the headman of Cuscowilla, gave Bartram the name “Puc-puggy,” the Flower Hunter. He later canoed up the St. Johns River, battling alligators and revisiting sites he had seen with his father.

When Governor Wright signed a peace treaty with a delegation of Creek leaders in October 1774, Bartram decided that it was safe to embark on his deferred tour of the Indian country. Though he did not refer to it in his journal, the Revolutionary movement gathered momentum in Charleston and along the Georgia coast. Bartram, by choice and disposition a Quaker, tried to remain neutral.

Bartram’s effusive description of the Cherokee mountains continues to attract tourists today. After visiting the Cherokee villages along the Little Tennessee River, Bartram returned to join a trading caravan headed for Mobile, Alabama, and the Creek country. He avoided Augusta and Savannah, where Sons of Liberty made life difficult for those who wished to remain neutral. Bartram’s journal provides the most valuable historical record of Creek life at the time of the American Revolution (1775-83). His travels took him to Mobile and Pensacola, Florida, and by boat to the Mississippi River.

When he returned to Savannah in January 1776, the Revolutionary War had begun. Georgians under the command of Bartram’s friend Lachlan McIntosh fought against British warships in the Savannah River. Neutrality was no longer an option for the Quaker. Though he did not mention it in his book of travels, Bartram’s private papers reveal that he actually participated in a skirmish with British soldiers and their Indian allies along the Florida border. As soon as he could, Bartram put the war behind him and returned to his father’s garden in Pennsylvania as something of a celebrity. He enjoyed eight months of companionship with his father before John Bartram died in September 1777.

Bartram wrote his book while the founding fathers drafted a constitution for the republic. He saw divine guidance at work in the shaping of the new country. “I foresee a magnificent structure and would be instrumental in its advancement,” he wrote. His book exalted the human spirit and celebrated the richness of America’s natural world. He called upon Americans to respect the rights of Indians, to eradicate slavery, and to live up to the best in themselves.

Bartram died at his family home near Philadelphia on July 22, 1823.