A member of the Georgia Aviation Hall of Fame, Atlanta resident Charles Dryden was one of the famed Tuskegee Airmen of World War II (1941-45), whose service helped usher in the desegregation of the U.S. armed forces. He also flew combat missions during the Korean War (1950-53).

Charles Walter Dryden was born in New York City on September 16, 1920, to Jamaican immigrants Violet and Charles Levy (or Levi) Tucker Dryden. He grew up with stories of his father’s experiences as a Jamaican sergeant during World War I (1917-18) and the daring exploits of Corporal Eugene Bullard (the “Black Swallow of Death”), the famed African American fighter pilot. Both parents had taught at colleges in Jamaica.

Dryden graduated from Stuyvesant High School in 1938. He received a bachelor’s degree in political science from Hofstra University, in New York, in 1955 and a master of arts in public law and government from Columbia University, also in New York, in 1957. With his first wife, he had three children. He later married Marymal Morgan.

In the early 1940s, his focus was on joining the U.S. Army Air Corps’ program to develop African American pilots at a new training center located near the Tuskegee Institute in central Alabama. Authorized by U.S. president Franklin D. Roosevelt’s 1940 executive order to form an all-Black flying unit, classes began in June 1941, resulting in the formation of the Ninety-ninth Pursuit (later Fighter) Squadron. Dryden was one of 992 African Americans who eventually became military pilots at Tuskegee.

Courtesy of Museum of Aviation

In August 1941 Dryden gained a place in what would become the second class to finish Aviation Cadet Training (in April 1942). One of three to graduate from this class, Second Lieutenant Dryden soon gained the nickname “A-Train,” partly from the famed Duke Ellington song and partly from his New York City background, which conjured images of the Eighth Avenue subway express.

Flying P-40F Warhawks, the Ninety-ninth Fighter Squadron was commanded by Captain Benjamin O. Davis Jr. Despite an excellent training record, progress toward the unit’s combat deployment proved slow. In April 1943 the airmen arrived in Tunisia, in North Africa, but did not see their first action until June in Italy. On June 9 First Lieutenant Dryden led five other fighters into combat against German aircraft over the Sicilian town of Pantelleria, the first time the African American pilots had engaged the enemy while flying for the U.S. Army Air Corps. The Ninety-ninth maintained relentless air attacks, and two days later the town’s Italian garrison surrendered.

Throughout the remainder of the war, the Tuskegee Airmen had a remarkable record. In July 1944 the Ninety-ninth Fighter Squadron became part of the 332nd Fighter Group, an all-Black command made up of pilots trained at Tuskegee. Soon after, they began flying P-51 Mustangs, nicknamed “Red Tails” for their distinctive unit markings.

While Dryden and his comrades performed many duties, it was as bomber escorts that they excelled. By the end of the war, many B-17 and B-24 pilots of the Ninth and Fifteenth air forces began to request “those P-51s with the red tails.” All totaled, Dryden and his fellow Tuskegee Airmen flew more than 15,000 combat sorties, destroying more than 250 enemy aircraft as well as 950 railcars, trucks, and other motor vehicles. They never lost a single escorted bomber to enemy action.

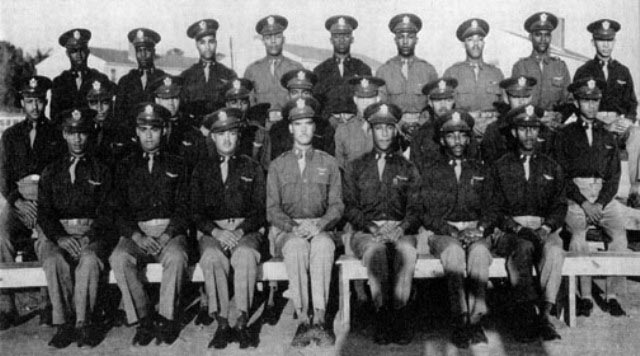

Image from Alan Wilson

But this success came at a high price: sixty-six of Dryden’s fellows were killed in action, and thirty-two became prisoners of war. For their efforts the men won 150 Distinguished Flying Crosses (an award first given to Charles Lindbergh), 744 Air Medals, eight Purple Hearts, and fourteen Bronze Stars. Their achievements convinced many white veterans that African Americans were every bit their equals and deserved better treatment back home. As a result, on July 26, 1948, U.S. president Harry S. Truman signed the executive order that desegregated the U.S. military.

A command pilot with more than 4,000 flying hours, including combat missions during the Korean War, Dryden retired in 1962 after twenty-one years with the air force. That same year, he also retired from his post as an Air Science professor at Howard University in Washington, D.C. He remained an active citizen, though, serving as committeeman in Matawan Township, New Jersey, from 1963 to 1965. A job at Lockheed-Georgia later brought Dryden to Atlanta where, in 1978, he founded the Atlanta Chapter Tuskegee Airmen Inc. He returned to Tuskegee on several occasions for reunions and other special events and also worked to help other minority aviation students and cadets realize their dreams.

Dryden received an honorary doctorate of humane letters from Hofstra University in 1996. The following year brought further attention to his accomplishments: Georgia secretary of state Max Cleland proclaimed him an “Outstanding Georgia Citizen”; he participated in the opening of the Museum of Aviation display “America’s Black Eagles: The Tuskegee Pioneers and Beyond”; and he published his autobiography, A-Train: Memoirs of a Tuskegee Airman. In 1998 he was inducted into the Georgia Aviation Hall of Fame.

Dryden remained an important friend and supporter of the Museum of Aviation for the rest of his life, often speaking to youth and college groups to encourage them to seek careers in military and civilian aviation. In July 2007 he flew with around 200 students from the Aviation Career Education program in Atlanta to the National Museum of the United States Air Force at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base near Dayton, Ohio, to present the museum with a replica of the Congressional Gold Medal awarded to the Tuskegee Airmen in March 2007. The students’ flight was partially sponsored by Delta Air Lines.

Dryden died in Atlanta on June 24, 2008. Former Atlanta mayor and U.S. ambassador Andrew Young delivered the eulogy at his funeral.