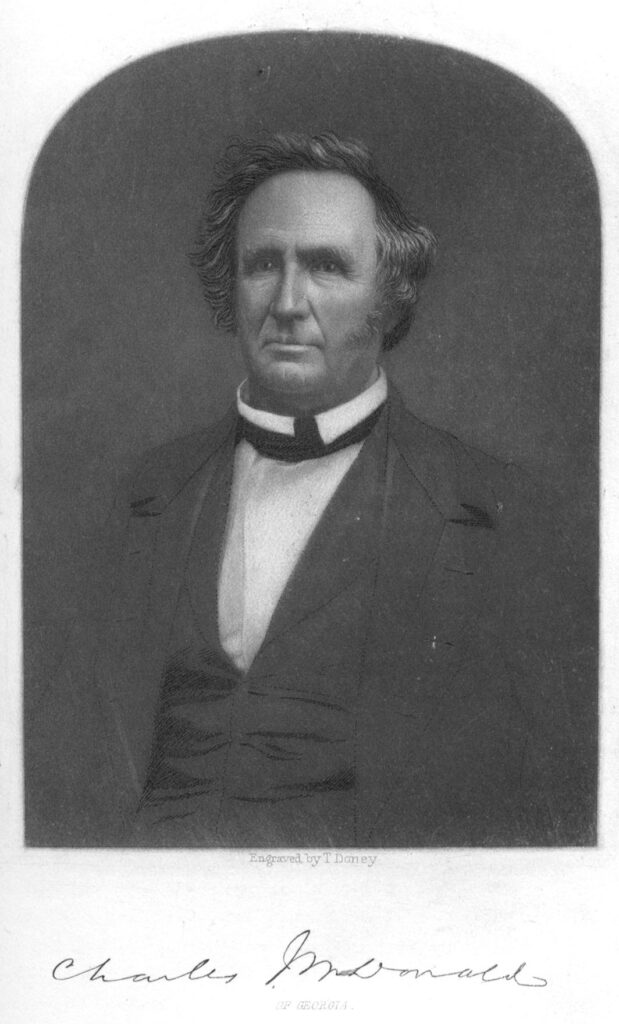

Charles McDonald spent two terms as governor of Georgia during the tumultuous years following the economic panic of 1837. While in office, he helped to restore public confidence in the state’s finances and government. After his four-year tenure McDonald became an advocate for states’ rights.

Charles James McDonald was born in Charleston, South Carolina, on July 9, 1793, to Mary Glas Burn and Charles McDonald. McDonald moved with his parents, who were Scottish immigrants, from South Carolina to Hancock County as an infant. He attended the Reverend Nathan Beman’s academy at Mount Zion before entering South Carolina College, where he received his A.B. degree in 1816.

After a year of studying law, McDonald was admitted to the Georgia bar, and he soon developed a lucrative legal practice and bought his own plantation in Bibb County. In 1822 he entered public service as the solicitor general for the Superior Court of the Flint Judicial Circuit in Henry County, and three years later he was sitting as a judge for the same court.

In 1825 McDonald moved to Macon, the hometown of his wife, Anne Franklin. There the couple raised three daughters and two sons. In 1830, at the age of thirty-seven, he retired from the bench. His wife died in 1835, and four years later he married Elizabeth Roane Ruffin.

Pushing southern industrialization while in Macon, McDonald invested heavily in railroad development, continued his law practice, and entered into land speculation. Also during this time he served a one-year term in the Georgia House of Representatives and two one-year terms in the state senate, and he was active in the Georgia militia as a brigadier general.

In 1839 he ran as a Democratic Party candidate for governor. Beating the Whig Party candidate, Charles Dougherty, by less than 2,000 votes, McDonald began the first of his two terms that lasted until 1843. McDonald was the second governor to inhabit the Old Governor’s Mansion in Milledgeville, then the state capital.

At the time of his election, Georgia’s economy was reeling from the panic of 1837. Cotton had dropped to four or five cents per pound, and commerce had come to a standstill. With nearly $1 million in state debt and an empty treasury, McDonald set himself the task of reviving the state economy, but he faced an uphill battle.

The Democratic Party held only a small majority in the state legislature, and by 1840 the Whigs controlled the General Assembly. Still, McDonald convinced the state legislature to repeal county control of property taxes, which had been grossly mismanaged, and to direct those funds into state coffers. Then, vetoing a Whig bill that granted a 20 percent tax cut to property owners, he proposed a tax increase but was initially defeated. Undaunted, the governor ordered the state’s treasurer not to pay the legislators’ salaries until all other state expenses had been paid. Decrying McDonald’s supposedly tyrannical order, the state legislature nonetheless approved a 25 percent general property tax increase.

For the next eight years after leaving the governor’s mansion, McDonald developed his business interests and focused his efforts on the establishment of a mill town in what was then Campbell County (present-day Douglas County). Built on Sweetwater Creek in 1848, his factory employed 60 workers and produced 750 yards of cloth per day by the time of the Civil War (1861-65). (In 1864 Union general William T. Sherman ordered the entire community burned, but the ruins of the factory are now a prominent tourist attraction in Sweetwater Creek State Park.)

McDonald held a strict constructionist view of the U.S. Constitution, which led him to support a state’s ability to secede from the Union and to reject the Compromise of 1850. In that vein, he left the Unionist Party and became the Southern Rights’ Party candidate for governor in 1851, losing to Howell Cobb by a large margin.

Withdrawing from politics, McDonald sold his Bibb County plantation and bought one in Cobb County. From 1855 to 1859 he served as a justice on the Supreme Court of Georgia. Because of poor health, he retired to his home in Marietta, known as Kennesaw Hall. At the time of his death on December 16, 1860, McDonald owned fifty-three enslaved people and held property worth $127,800.