Before 1972 Georgia and other states that provided for capital punishment used systems that gave juries broad discretion in deciding whether to impose the death penalty on persons convicted of death-eligible offenses. In Furman v. Georgia, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down this feature of Georgia’s capital sentencing scheme and in effect invalidated the death penalty, as then administered, throughout the United States.

The Court, in a five-to-four decision, reasoned that capital sentencing based on the unguided discretion of juries offends the “cruel and unusual punishment” clause of the Eighth Amendment, because it permits juries to impose the distinctively profound sentence of death on some convicted defendants while other juries impose the far different sentence of life imprisonment on large numbers of similarly situated defendants convicted of exactly the same crime. There was no majority opinion written for Furman, but Justice Potter Stewart captured the thought of a critical group of justices when he wrote, “These death sentences are cruel and unusual in the same way that being struck by lightning is cruel and unusual.” The Eighth Amendment, he explained, “cannot tolerate the infliction of a sentence of death under legal systems that permit this unique penalty to be so wantonly and so freakishly imposed.”

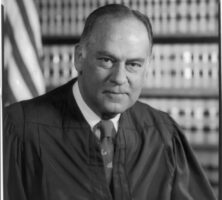

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

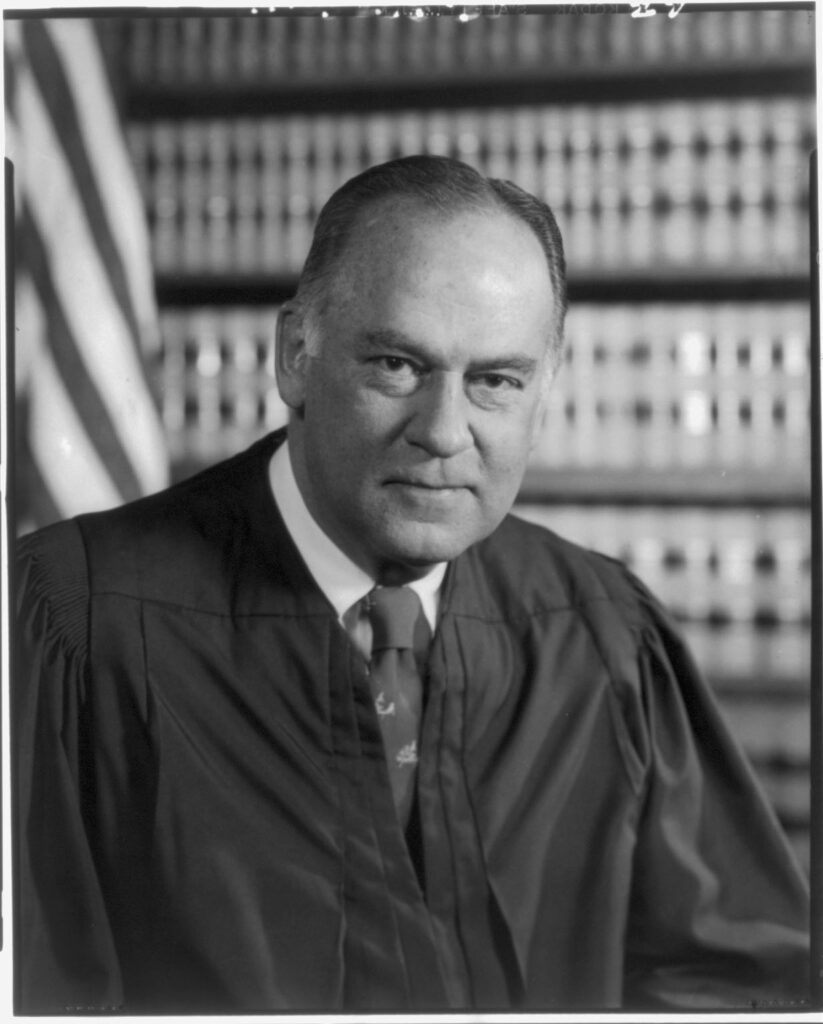

In a dissenting opinion joined by four members of the Court, Chief Justice Warren Burger argued that, while “the Eighth Amendment forbids the imposition of punishments that are so cruel and inhumane as to violate society’s standards of civilized conduct,” the amendment “most assuredly does not speak to the power of legislatures to confer sentencing discretion on juries.” In his view a long history of acceptance, the legal system’s “basic trust in lay jurors,” and “the primacy of the legislative role” in fixing criminal punishments rendered the death penalty constitutional, even when imposed pursuant to unguided-discretion sentencing schemes.