William Burnham Woods, an Ohio native, was a Georgia resident at the time of his appointment to the U.S. Supreme Court. His circuitous route to the Peach State, coupled with his numerous previous addresses, has led other states to claim him as their own. In the end, however, it is a battle over a limited legacy, for Woods’s short tenure on the Court, from 1881 to 1887, was workmanlike at best and had little long-term historical impact.

Education and Early Career

Woods was born on August 3, 1824, in Newark, Ohio, to Sarah and Ezekiel Woods, a merchant-farmer. He started college at Western Reserve College (later Case Western Reserve University) in Hudson, Ohio, before heading east to Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, from which he graduated with honors in 1845. Returning to Ohio, he studied law with S. D. King, and in 1847 he was admitted to the Ohio bar and became King’s partner. In 1855 Woods married Anne E. Warner, and the couple had two children, a boy and a girl.

A family man with an established legal practice, Woods turned his attention to politics. Although originally a Whig, he ran as a Democrat when first elected mayor of Newark in 1856. The following year he won election to the Ohio state legislature, where he was selected Speaker of the House in only his second term. In 1859, after the newly formed Republican Party gained the majority in the Ohio legislature, he became the minority leader and initially opposed the Republican agenda.

With the onset of the Civil War (1861-65), however, Woods put his national loyalties ahead of his partisan ones, not only supporting U.S. president Abraham Lincoln’s effort to raise an army and preserve the union but also joining the army in 1862 as a lieutenant colonel in the 76th Ohio Volunteer Infantry. Ultimately achieving the rank of major general, he saw action at the battles of Shiloh and Vicksburg, in Tennessee and Mississippi respectively. Ironically, Woods’s introduction to Georgia was as a member of Union general William T. Sherman’s invading forces and included a lengthy march across the state to the sea.

Judicial Career

After the war, Woods was assigned to a post in Alabama. When his military service ended, he decided to remain there, his brother-in-law having already won election as a U.S. senator from that state. With Republicans clearly dominant in the Reconstruction South, the politically ambitious Woods again switched his allegiance, winning election to the Middle Chancery Court in 1868 as a Republican. He served in that post for almost two years before his wartime association with U.S. president Ulysses S. Grant, the former general of the Union Army, helped him secure an appointment as a federal district judge for the Fifth Circuit in 1869. As a circuit judge he spent much of his time riding between states to hear cases, and amid the travel he and his family moved to Atlanta in 1877.

Woods’s work on the circuit court was well received. He acted as a reporter for the rulings of the federal courts and made sure that the decisions were published and available for practicing attorneys. He worked hard to ensure that the law was administered fairly and that all rights were protected, no small thing in a South still feeling besieged by the specter of Reconstruction. Indeed, despite his northern upbringing and service in the Union army, Woods was well regarded throughout the South, earning universal respect for his evenhanded efforts across the region.

Tenure on U.S. Supreme Court

That high regard proved a great virtue when U.S. president Rutherford B. Hayes began to make appointments to the U.S. Supreme Court. With his own tenure in the White House clouded by the disputed results of the 1876 election, Hayes needed nominees whose appointments to the Court could help heal the still-fresh wounds of the Civil War. Hayes’s first appointee in 1877 was political ally and border-state resident John Marshall Harlan, and three years later he appointed Woods to replace Justice William Strong, who resigned in 1880. Although some objected to the lame duck Hayes making the appointment, Woods enjoyed strong support—his sponsors ranged from General Sherman to former Supreme Court justice John Archibald Campbell, a Georgia native and Alabama resident who had resigned his seat in order to serve the Confederacy. Woods was confirmed on January 5, 1881, less than a week after his formal nomination, becoming the first southerner appointed to the Court since 1853.

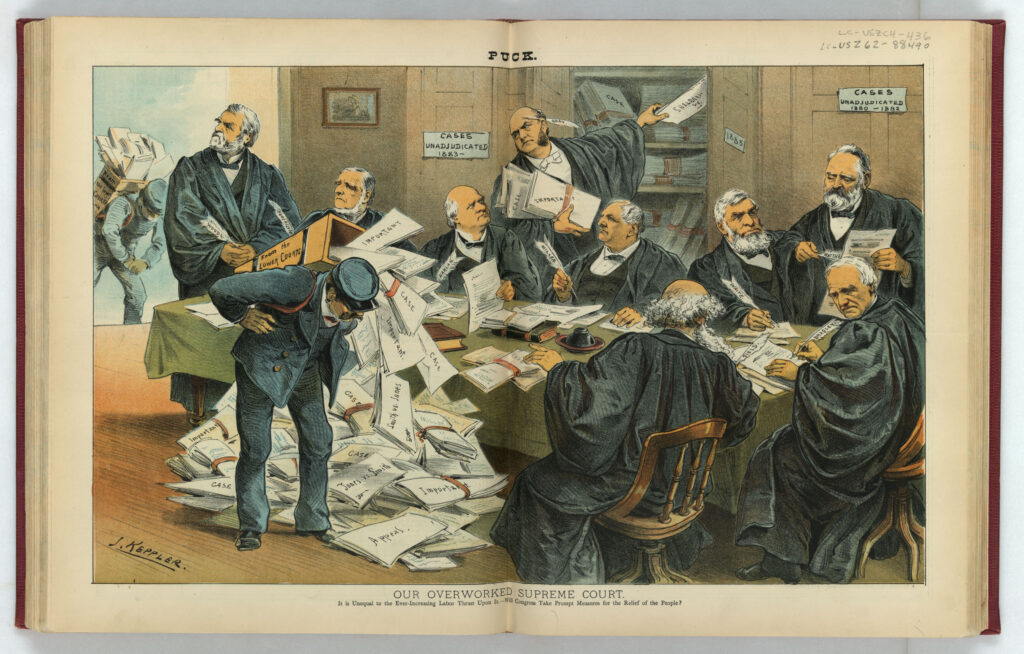

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Woods’s years on the Court were generally undistinguished. While he worked hard, he seldom strayed from the majority’s path, and his dissents were rare. A competent legal craftsman who wrote more than his share of opinions, his talents nevertheless paled alongside those of Harlan, Joseph Bradley, Stephen Field, and Samuel Miller. Too, his limited term on the Court gave him scant opportunity to develop a distinctive philosophy or voice.

His two most significant opinions illustrate both his judicial approach as well as the comparatively controversy-free era during which he served. In United States v. Harris (1883) the Court struck down the Ku Klux Klan Act of 1871. In an early interpretation of the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, the Court limited the reach of the federal government, declaring that any regulation of individual activity had to originate at the state level. Meanwhile, in Presser v. Illinois (1886), Woods’s majority opinion declared that the Second Amendment had no application in a challenge to an Illinois law limiting an individual’s right to parade with a firearm. The Second Amendment, Woodswrote, applied only to efforts by the federal government to limit the right of a citizen to bear arms.

Woods fell ill in the spring of 1886. He never recovered and was unable to participate in the Court’s active business during his final term. He died a year later in Washington, D.C., on May 14, 1887.