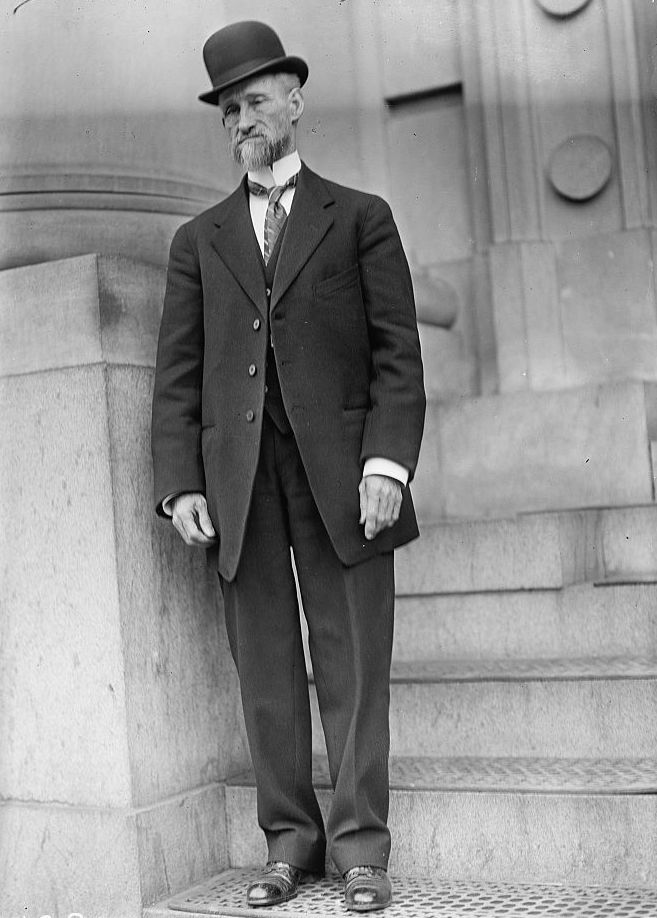

Joseph M. Brown served as Georgia’s governor for two terms, from 1909 to 1911 and from 1912 to 1913.

Born on December 28, 1851, in Canton, Joseph Mackey Brown was the son of Elizabeth Grisham and Joseph E. Brown, who was the governor of Georgia during the Civil War (1861-65). The young Brown was often called “Little Joe Brown” by his family. After graduating from Oglethorpe University in 1872, Brown studied law at both Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and his brother’s law practice in Georgia. He passed the bar in 1873 but because of his deteriorating eyesight did not practice law. Instead, Brown attended a business college in Atlanta and, upon graduation, entered the field of transportation administration as a clerk with the Western and Atlantic Railroad. By 1889 Brown had risen to the position of traffic manager for the entire Western and Atlantic Railroad system; that same year he married Cora Annie McCord.

Brown wrote two books during his time with the railroad. The Mountain Campaigns in Georgia (1886) is a short illustrated Civil War military history of events along the Western and Atlantic tracks. His second book, Astyanax (1907), is an ambitious work of fiction set in pre-Columbian America. This epic tale chronicles the life of fictional warrior Astyanax, who travels among Native American empires in Central America fighting battles; losing and regaining his beloved sweetheart, Columbia; and eventually becoming king of an empire.

Georgia governor Joseph M. Terrell gave Brown his first major political post when he appointed him to the Georgia State Railroad Commission in 1904. Brown lost his position on the commission in August 1907, however, after a sharp disagreement with Terrell’s successor, Governor Hoke Smith. Smith sought to lower passenger fares to alleviate the economic pressure on his constituents, but Brown voted against the measure.

Brown entered the next gubernatorial election, in 1908, and won against Smith, despite having made no public speeches. Smith’s unpopular economic policies and the loss of his political support from the Populist leader Thomas E. Watson helped Brown become Georgia’s sixty-second governor. Brown’s successful campaign slogan was “Hoke and Hunger, Brown and Bread.”

Smith, however, did not relent in his criticism of Brown. In 1910 Smith narrowly defeated Brown in the Democratic primary election for governor. Brown refused to give up, however, and ran as an independent in the general election. Nonetheless, he lost to Smith. Shortly after taking office, Smith left the governorship to fill the U.S. Senate seat of Alexander S. Clay, who had died. Subsequently, Brown decided to run again for the governorship and was unopposed; he became Georgia’s sixty-fifth governor in January 1912, filling out the term Smith had vacated. The political feud between Smith and Brown continued. Brown ran against Smith in 1914 for the U.S. Senate; Smith defeated Brown in that election, and Brown never again returned to elected office.

During his two terms as governor, Brown advocated the prohibition of alcohol and a reduction in the state tax rate, and supported the formation of a state department of labor. He signed into law Georgia’s first automobile registration, licensing, and regulation law, which included a prohibition on driving while intoxicated. He staunchly supported legislation that would have curtailed lobbying among government officials and signed into law a bill requiring the registration of all revolvers carried privately in the state.

During the period before and after the U.S. Senate race against Smith, Brown wrote several newspaper articles critical of the Leo Frank case and the judicial system in Georgia. Frank, a Jewish factory manager in Atlanta, was convicted of raping and murdering Mary Phagan, a young female employee. Brown, a lifelong Baptist, fanned the flames of anti-Semitism with his commentary. After Frank’s death sentence was commuted by Governor John M. Slaton, Brown asked rhetorically in the December 27, 1914, issue of the Augusta Chronicle whether Georgians should accept that “anybody except a Jew can be punished for a crime.” Less than a year later, Brown revisited the Frank case in the Macon Telegraph and encouraged “the people to form mobs” to ensure that justice was carried out in the case. On August 17, 1915, a mob of white men indeed seized Frank from his prison cell in Milledgeville and lynched him in Marietta, a plan in which the former governor was almost certainly among the instigators.

After leaving politics, Brown spent his final years in Marietta. There he became a banker for a decade, holding the office of director and vice president of the First National Bank of Marietta. He also became the owner and operator of Cherokee Mills in Marietta. Brown died on March 3, 1932, and is buried in Oakland Cemetery in Atlanta.