On May 8, 2003, Governor Sonny Perdue signed legislation creating a new state flag for Georgia. The new banner became effective immediately, giving Georgia its third state flag in only twenty-seven months—a national record. Georgia also leads the nation in the number and variety of different state flags.

Early History

Throughout the colonial and antebellum eras, countless local militia companies organized in Georgia, as in many other southern states. Militia units needed weapons, uniforms, and flags—so it would be expected that some type of flag to symbolize Georgia would have developed. Most militia flags were sewn by members’ wives or other women in the community, and any number of design possibilities could result. The militia flags did have a common element, however: the coat of arms from Georgia’s state seal, adopted in 1799.

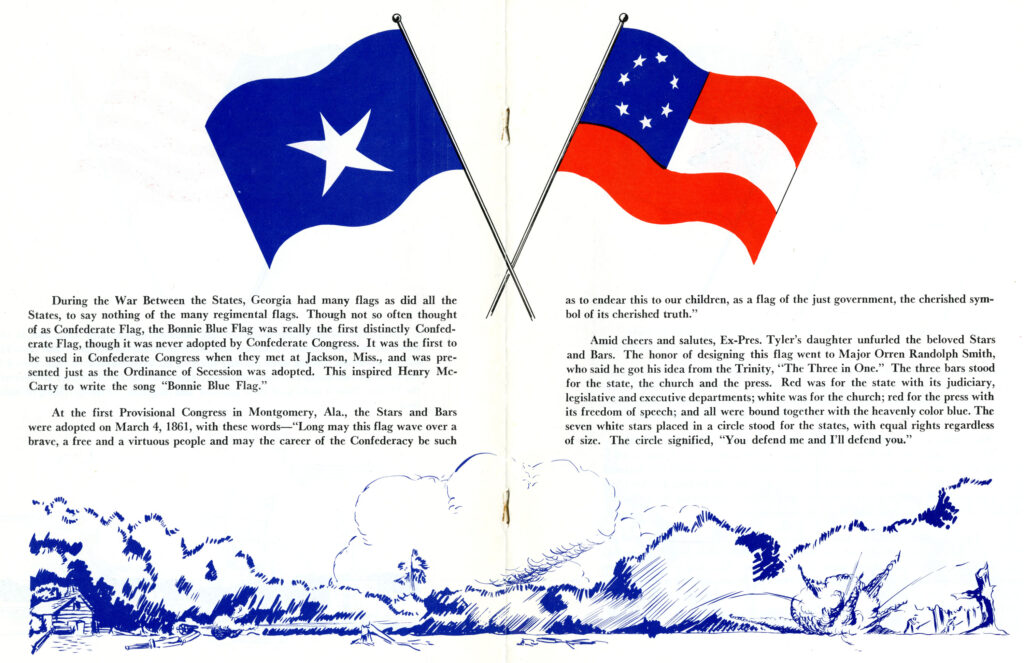

On the eve of the Civil War (1861-65), Georgia did not have an official state flag. After the state’s secession from the Union on January 19, 1861, there were several newspaper reports of secession flags consisting of a single star on a solid background. Although the “Bonnie Blue Flag” is the best known example, a better documented flag consisted of a single red star on a white field.

Photograph from Wikimedia

After secession the legislature ordered that state statutes be recodified to reflect Georgia’s new status. The new laws contained a provision requiring the governor to supply regimental flags to any Georgia militia units assigned to duty outside the state. These flags were to bear the “arms of the State” and the name of the regiment but did not specify the colors of the arms or the flag’s field. The coat of arms was the three-columned arch found in the center of the state seal. On some flags the coat of arms was white or gold, and on some it was in full color; the background on several surviving flags is blue.

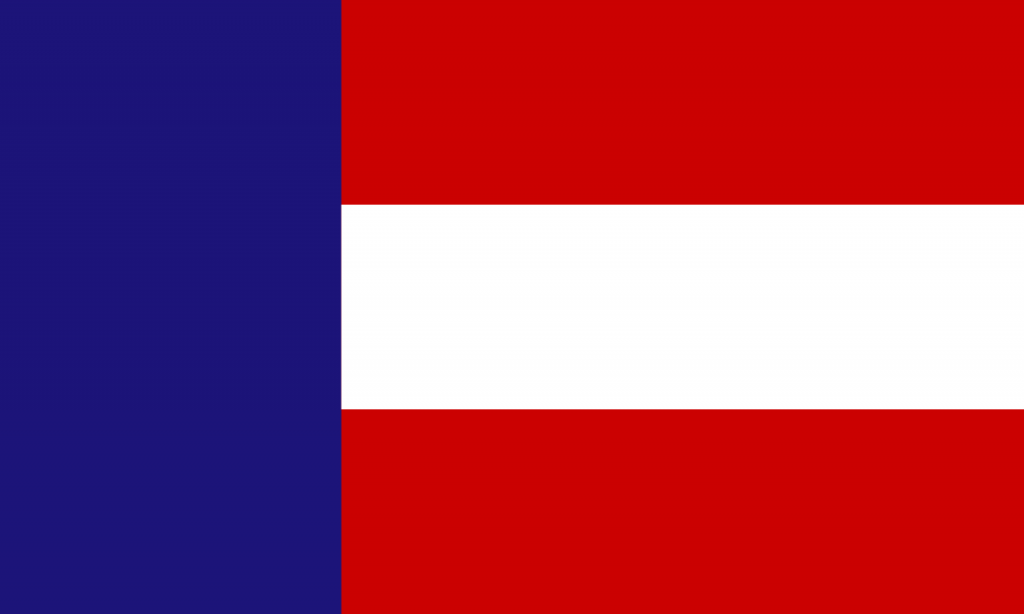

Presumably, this flag continued as Georgia’s unofficial banner after the Civil War’s end in 1865. In 1879 Heman H. Perry, a state senator and a former Confederate major, introduced legislation to give Georgia militia units an official state flag. The new banner was based on the first national flag of the Confederacy (the “Stars and Bars”). The blue canton (the top inner quarter) of the Stars and Bars extended the full width of the flag, and even though the stars were removed, the derivation of the flag was obvious to all.

Image from Wikimedia

Perhaps because the 1879 flag was devoid of state symbols, the Georgia General Assembly in 1902 stipulated: “On the blue field shall be stamped, painted or embroidered the coat of arms of the State.” The few surviving flags from this era show a coat of arms on the blue vertical band.

And perhaps because there was no standard way to display the coat of arms, flag makers soon began to construct different versions of the state flag. In some cases only the coat of arms was used. Increasingly, however, the coat of arms was shown within a circle or on a gold-outlined white shield. In some cases the date “1799” (the year the seal was adopted) and a red ribbon with the word “Georgia” were added beneath the shield. In 1914 the General Assembly changed the date on the state seal to the year of American independence, 1776, and flag designs that included a date beneath the coat of arms followed suit.

The next change came in the 1920s, when the entire state seal began appearing in place of the coat of arms. It is not known who authorized the substitution, or when. Georgia’s secretary of state may have ordered—or at least approved—the change, because the first state publication to show the seal on the flag was the 1927 volume of the Georgia Official Register, published by the secretary of state.

Surviving flags from the first half of the twentieth century show many variations. The coat of arms and seal often were depicted in color—usually gold or yellow, red, and blue on a white background—but sometimes the components of the seal were outlined in blue with gold or yellow fill. In time, however, the seal came to be depicted on a white background. Furthermore, during this period there was no official printed image of the state seal, so different flag manufacturers used different seal designs.

In 1935 the General Assembly passed a joint resolution adopting a pledge of allegiance to the state flag, which Governor Eugene Talmadge signed into law. The pledge incorporates the state motto “Wisdom, justice, and moderation”:

I pledge allegiance to the Georgia flag and to the principles for which it stands: Wisdom, Justice, and Moderation

Georgia’s 1956 Flag

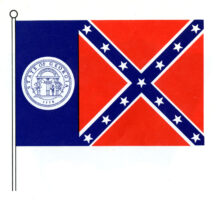

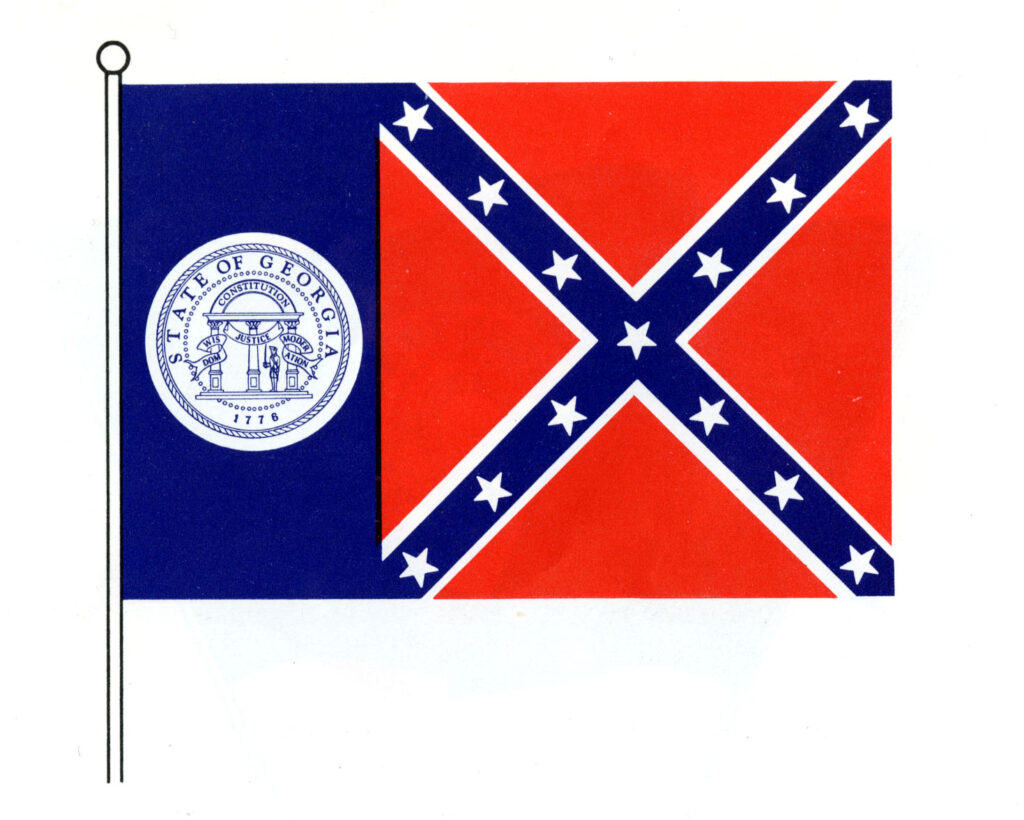

In 1955 the Atlanta attorney and state Democratic Party leader John Sammons Bell began a campaign to substitute the square Confederate battle flag for the red and white bars on Georgia’s state flag. Along with Bell, state senators Jefferson Lee Davis and Willis Harden, who were well known for their interest in Georgia’s Confederate history, agreed to introduce legislation to change the state flag. Some legislators favored the adoption of a standard state flag as an appropriate way to mark the upcoming centennial of the Civil War. A strong impetus for change, however, was the 1954 and 1955 Brown v. Board of Education decisions, which were bitterly denounced by most Georgia political leaders. The entire 1956 legislative session was devoted to Governor Marvin Griffin’s platform of “massive resistance” to federally imposed integration of public schools. In this charged atmosphere, legislation to put the Confederate battle flag on Georgia’s state flag sailed through the General Assembly.

Unlike Mississippi’s state flag, where the Confederate battle emblem appeared only on the flag’s canton, Georgia devoted two-thirds of its state banner to the Stars and Bars. The day after the vote in the house, Representative Denmark Groover, Governor Griffin’s floor leader, told the press that the new flag “will show that we in Georgia intend to uphold what we stood for, will stand for and will fight for”—meaning, chiefly, legal segregation and a strict interpretation of the U.S. Constitution.

The flag bill went through the legislature with no public hearings and attracted little attention in the press. There was no provision for submitting the new flag design to the voters in a statewide referendum, because under the state constitution, the legislature had sole authority to choose the flag, and in any case there was no feeling that a referendum was needed.

By the late 1960s, at the height of the civil rights movement, some Georgians were saying that the Confederate battle flag was not a proper symbol for a state flag. In 1969 state representative Janet Merritt introduced the first bill to return to the pre-1956 flag. By the early 1980s every session of the legislature saw attempts to change the flag, which was seen more and more as an issue dividing the state. Atlanta city officials soon began refusing to fly the 1956 flag at municipal buildings and facilities.

At the 1993 legislative session, Governor Zell Miller placed the weight of his office behind a return to the pre-1956 flag. Support for the Confederate battle emblem—particularly outside Atlanta—was stronger than he had anticipated, however. The issue almost cost Miller his reelection the next year, and he abandoned the fight during his second administration. As the 1996 Olympic Games approached, Atlanta city and business leaders tried hard to persuade the General Assembly to change the state flag—but without success.

A New State Flag

In 1998 former state representative and senator Roy Barnes was elected governor. Barnes, a Democrat, had been heavily supported by Black political leaders and won election in part because of a heavy Black turnout at the polls. In return, some African American legislators made clear their view that Georgia’s state flag now needed to be changed. In private the new governor agreed with them, but in public he was silent on when and how such change should come.

After the 2000 legislative session, an Atlanta architect, Cecil Alexander, met with Governor Barnes to talk about a proposal he had for a new state flag. Alexander proposed placing the seal of the state in the middle of the flag and situating six small flags that had flown over Georgia during its history—including the Confederate battle flag—beneath the large seal. Alexander had submitted his flag proposal in 1993 during the legislative flag debate, but few lawmakers were interested. When Alexander presented his proposed flag to Barnes, however, the governor professed interest in the concept, although he suggested some changes to the design: instead of six small historical flags, there would be five flags on a gold ribbon with the caption “Georgia’s History.” Alexander agreed to the changes to his design.

Photograph from Wikimedia

During January 2001 Governor Barnes began holding meetings with a small group of legislative leaders and some African American members who had long sought to change Georgia’s flag. A plan was devised whereby House Bill 16 (a bill prescribing a return to the pre-1956 flag and the redesignation of the 1956 flag as the “Georgia Memorial Flag”) would be amended by committee substitute. Instead of the pre-1956 flag, Alexander’s modified design would become the new state flag.

Barnes’s strategy was to get HB 16 approved by the state House of Representatives before the opposition could organize. This would mean using the full extent of his informal powers to secure the votes necessary for a bill to pass in the house. The committee substitute was introduced on January 24, 2001, and was immediately transmitted to the full house, where it passed. Only one floor amendment was approved—to add “In God We Trust” at the bottom of the flag. On January 30 the senate passed the bill. It was then sent to Governor Barnes, who signed the bill into law. Moments later, without fanfare, a new flag was flying over Georgia’s state capitol.

Although the margin of victory was not wide, the governor had been extremely effective in securing the support of wavering legislators. Various coalitions crossing racial and party lines had formed. Concessions were made to placate traditionalists—for example, a provision in the bill that would protect Confederate monuments on public property. One of the most important factors in persuading some rural white legislators to vote for the new flag was the testimony of Denmark Groover, who had served as Governor Griffin’s floor leader at the 1956 session. Groover had repeatedly denied that the 1956 change was racially motivated. Now nearly seventy-nine and dying of cancer, he admitted that anger over the federal government’s support of integration had indeed been a factor and called on Georgia legislators to put the flag issue to rest.

Supporters of the new flag were jubiliant, though there was some concern that the design was too detailed. In truth, the flag violated many canons of flag design; the North American Vexillogical Association rated the new Georgia flag as the worst-designed state or provincial flag in North America. But for Governor Barnes, the new flag’s political significance far outshadowed its aesthetic shortcomings.

Supporters of the 1956 flag were shocked and outraged. Organized opposition to the “Barnes flag” (or “Barnes’s rag,” as some critics liked to call it) was led by such organizations as the Sons of Confederate Veterans and the Heritage Preservation Association. There were also many unorganized expressions of resentment, in the form of “Boot Barnes” bumper stickers, yard signs, and home flagpoles flying the 1956 flag. The “flaggers” staged protests at almost every public event that the governor attended.

Flaggers readied for the 2002 general election, aiming not only at Barnes but also at state legislators who had voted to replace the old flag. Republican challenger Sonny Perdue made known his belief that Georgians should have a chance to vote on their state flag. He never specified which flag or flags would be on the ballot, but flaggers interpreted his comments to mean that he wanted Georgians to have a chance to vote on the 1956 flag.

Throughout the general election contest, polls consistently showed Governor Barnes leading Perdue. In reality, however, the flaggers were only the most vocal of Barnes’s detractors; a coalition of groups critical of Barnes’s handling of several different issues was coming together as election day neared. On the morning after election day, it was confirmed that Perdue had won an upset victory. Governor Perdue now had to deliver on his campaign promise to allow a referendum. The question was whether he would allow the 1956 flag to appear on the ballot.

Courtesy of Special Collections & Archives, Georgia State University Library.

Yet Another New Flag

In February 2003 a proposal, designated House Bill 380, was introduced to hold a nonbinding referendum on the flag that had been adopted in 2001. In conjunction with the March 2004 presidential primary election, voters would be asked to answer yes or no on keeping the current flag and, in case the majority rejected the current flag, to express their preference for either the pre-1956 or the 1956 state flag. Although the General Assembly would not be bound by the referendum, Black members of the house feared that placing the 1956 state flag on the referendum ballot would open the door for its return—something they unanimously rejected. As a result, HB 380 remained in committee throughout February and March.

Photograph from Wikimedia

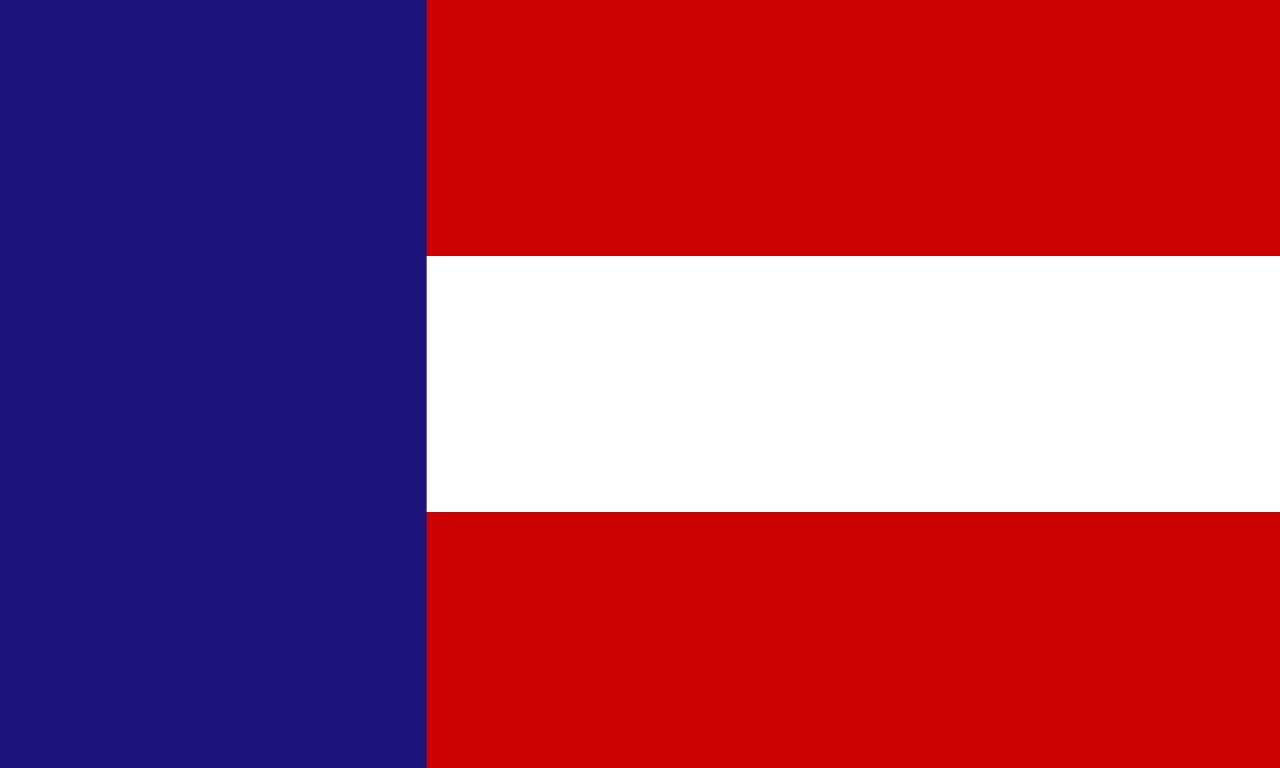

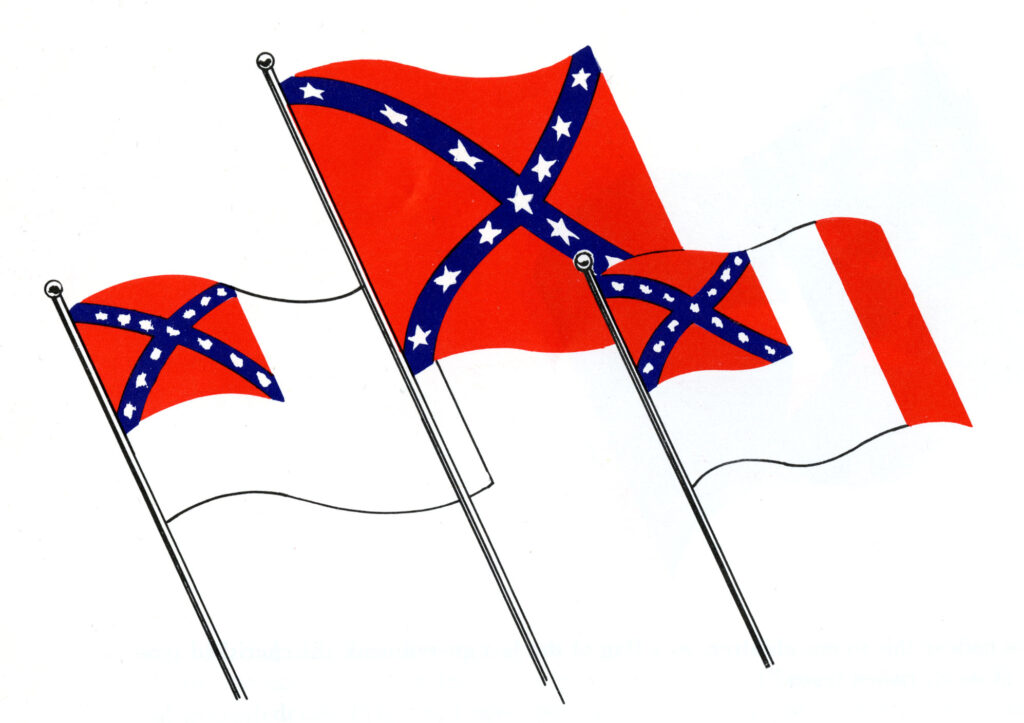

By early April, however, an amended version of HB 380 was introduced. The revised bill provided that the 2001 flag be replaced with a new Georgia flag that incorporated the thirteen-star version of the first national flag of the Confederacy—the so-called Stars and Bars—with the Georgia state seal in the center of the circle of stars, plus the words “In God We Trust” in blue on the white bar of the flag. If HB 380 were approved by the General Assembly, then the new flag would become official immediately upon signing by the governor.

A binding statewide referendum would be held on the HB 380 flag, with no other choice on the ballot. If a majority of voters approved the HB 380 flag, then it would continue as the official state flag with no further involvement by the General Assembly or governor—and the matter of Georgia’s state flag would be settled. If the majority disapproved, then a second binding referendum would be held in July 2004, with two choices on the ballot—the pre-1956 flag and the 1956 flag. The results of this second referendum would determine Georgia’s official state flag, without any other action on the legislature’s part.

HB 380 as amended went to the house floor on April 8. After more than six hours of impassioned debate, the house passed the bill by a vote of 111–67. All 39 Black Democrats voted against the bill because of the second referendum provision, which could allow the return to the 1956 flag. Most white Democrats from rural areas had voted for the bill. It appeared that a potentially damaging split had developed within the Democratic Party, with Blacks and urban whites pitted against rural whites.

During consideration of HB 380, the house committee held no public hearings and therefore did not receive the benefit of expert testimony. This omission had serious consequences. There were several problems with the design, the most important of which was that the proposed flag would be longer than standard flags. On indoor flagpoles it would touch the floor, and on outdoor flagpoles it would extend two feet beyond the U.S. flag. Suddenly Georgia’s proposed new flag was making national and even international news.

Final Action?

The bill was presented to the state senate on the last day of the 2003 session. Its introduction began five hours of debate, during which more than half of the senators took the podium, some speaking with great emotion. Finally, it was time to vote on amendments to the bill. The most critical was Amendment 1, which addressed various problems with the flag’s design, especially its awkward dimensions. It called for a Georgia coat of arms in gold (rather than a white state seal) to be located inside a circle of thirteen white stars (and specified that those stars represented the thirteen original colonies rather than the Confederate states). It also provided that “In God We Trust” be located immediately beneath the coat of arms inside the circle of stars and charged the secretary of state with determining the flag’s dimensions and official specifications. The amendment passed, though the vote was very close, and the other, less controversial amendments were adopted as well. The amended bill then passed by a comfortable margin.

HB 380 was immediately transmitted to the house, where it was presented for a vote on the final day of the session. Confusion reigned. Black legislators announced that they would vote for HB 380, but only if there was to be just one referendum, between the current flag and the proposed new flag. Also, the bill was amended to make the March 2004 referendum an “advisory” vote, to eliminate constitutional questions about a binding referendum.

With fewer than three hours before mandatory adjournment at midnight, a floor vote was called. When the vote tally was announced, the result was 89-88 in favor. But 91 votes were needed for passage in the 180-member house, so a motion to reconsider the vote was made immediately and adopted. A second vote resulted in a vote of 90-86. The Speaker then cast his vote yea, and HB 380 had exactly the minimum number of votes for passage. But the senate still had to agree to the house amendment, and the clock was running out. In a quid pro quo, Black senators agreed to support the governor’s tobacco tax bill if senate Republicans would support the house amendment. With less than two hours to go before midnight, the senate adopted the amended bill, and the rough battle over HB 380 was finally over. Georgia would soon have a new flag—its third in twenty-seven months.

Although statewide polls in 2003 indicated that most Georgians were tired of the flag debate, the issue did not die. Some flaggers felt betrayed by politicians who had voted to remove the 1956 flag from the 2004 referendum, and they promised to seek revenge in future reelection campaigns. Georgia’s population has changed dramatically in recent decades, however, and recent polls have shown that only a minority of residents favor the Confederate battle emblem on the state flag.

Ironically, the new flag recognizes Georgia’s Confederate heritage by placing Georgia’s coat of arms and “In God We Trust” on the first national flag of the Confederacy. This legacy did not go unnoticed by African American legislators and others—but most expressed a willingness to allow this tribute because they did not see it as a symbol widely associated with racist groups.

In a statewide referendum held on March 2, 2004, Georgia voters had the opportunity to express their preference for either the new design or the 2001 design. Support for the new design was overwhelming, with more than 73 percent of voters selecting it over the flag adopted during Governor Barnes’s administration.

The long saga of Georgia’s state flag probably has ended. Still, some Georgians have intense feelings of loyalty to the Confederate battle symbol, and the 1956 state flag will doubtless be displayed on private property—particularly in rural areas—for years to come.