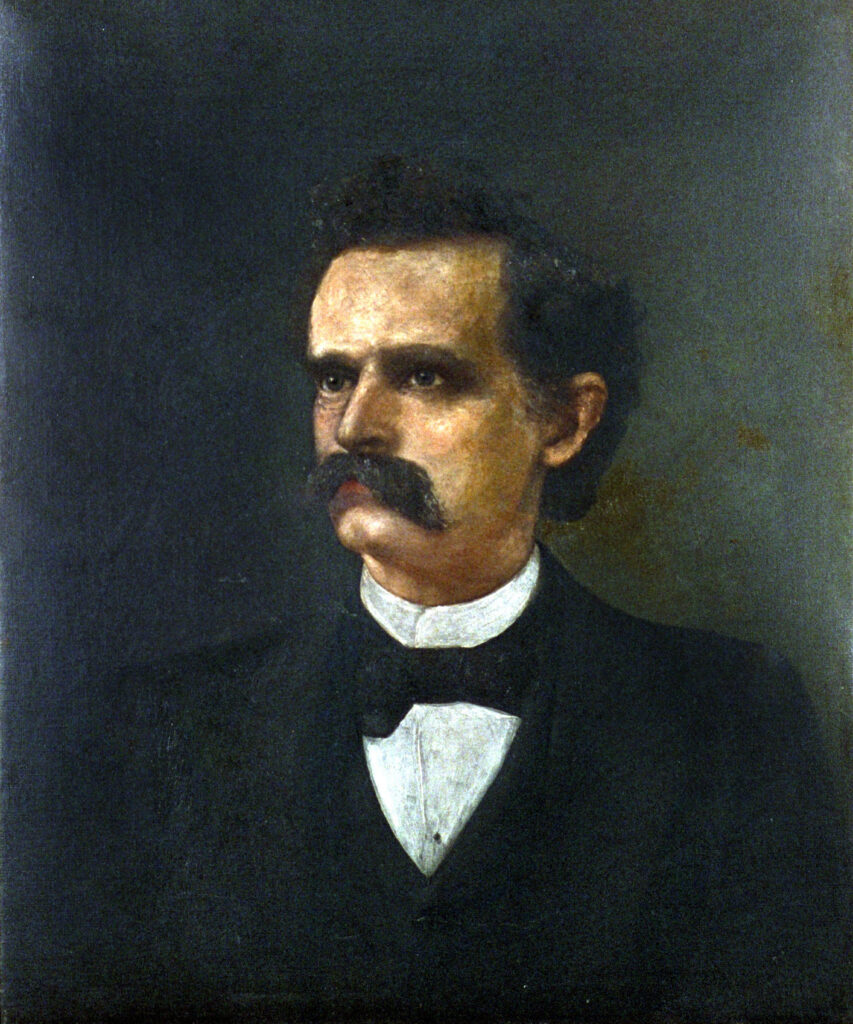

A noted proponent of education and credited with helping to establish the first state women’s college, William Y. Atkinson served two terms as governor of Georgia, from 1894 to 1898. His successful implementation of reform politics helped cut short the Populist threat to the state Democratic Party.

A lawyer-legislator from Newnan, Atkinson’s political ascent heralded the declining influence in Georgia of the old Confederates—the Redeemers—and of the so-called Bourbon Democrats, who advanced the interests of the state’s postwar urban capitalists and plantation-country elite. Atkinson emerged from among the ranks of young professionals entering state politics from the newly developing regions of Georgia. Atkinson County, created in 1917, is named for him.

William Yates Atkinson was born on November 11, 1854, in Oakland in Meriwether County. He was one of several children born to John Pepper Atkinson, an educated Virginia-born planter, and his second wife, Theodora Phelps Ellis of Putnam County. The large family had enough income to own enslaved people but was not so prosperous as to escape the necessity of working the farm themselves. In a setting characterized by modest means yet substantial education, culture, and devotion to a work ethic, Atkinson was able to overcome the limitations of his farmbound schooling, including the financial setback caused by his father’s death in 1873, and ultimately enter college and obtain a law degree. Thus, from the circumscribed prospects of a teenaged teamster who eked out meager savings for college by hauling cotton from Meriwether County to the town of Griffin, he rose to become the state’s chief executive officer.

State Legislator

In 1877, with a degree from the University of Georgia, Atkinson began practicing law in Newnan, and in 1879 Georgia governor Alfred H. Colquitt appointed him solicitor of the Coweta Judicial Circuit court. Atkinson was married in 1880 to Susan Cobb Milton, a granddaughter of Florida’s Confederate governor, who proved to be an energetic and indispensable partner in her husband’s political career, as well as a successful businesswoman after his death. (Their six children included a future justice of the Supreme Court of Georgia, William Yates Atkinson Jr.)

In 1886 Atkinson won the first of his four terms in the state legislature, where he amassed a record of effective service to his county and involved himself in important statewide issues like education, taxation, and regulatory authorities. As he earned a reputation for practicality and diligence in the state House of Representatives, Atkinson gained appointment to progressively more important committees, such as those responsible for elections, tax revenue, the judiciary, and railroad regulations.

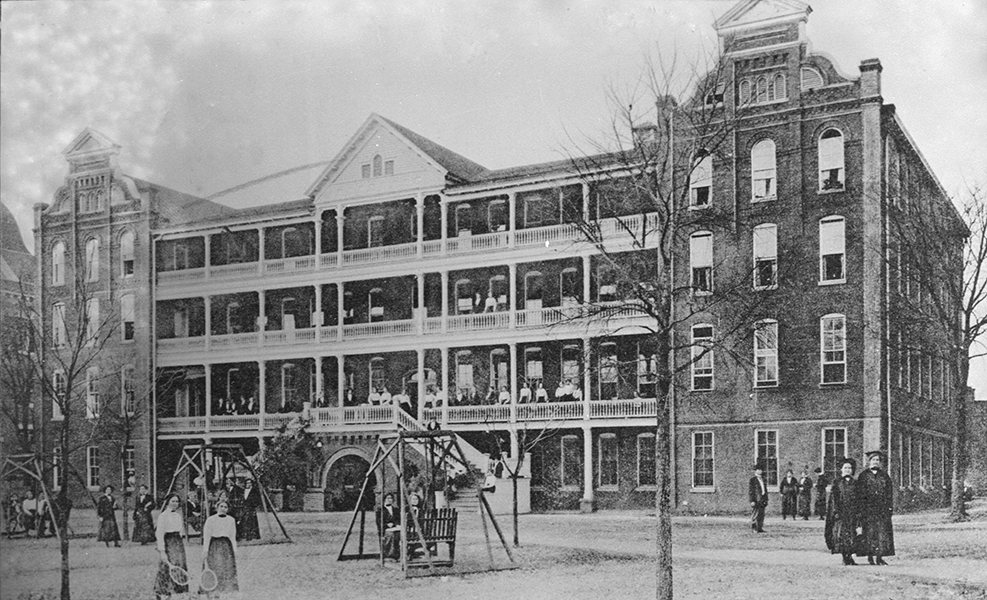

A staunch friend of education throughout his political career, Atkinson was behind noteworthy legislation to establish the Georgia Normal and Industrial College (later Georgia College and State University) at Milledgeville and supported the establishment of the textile department at the Georgia School of Technology (later Georgia Institute of Technology). He also sponsored bills to make the state agricultural commissioner an elected office, to limit oil inspectors’ pay, and to give the state railroad commission regulatory power over telegraph and express companies.

As his legislative experience grew and his considerable abilities were recognized by party colleagues, he garnered plum appointments to increasingly important posts inside the party organization, positions upon which he would build the foundation for his eventual campaign for governor. In 1890 he managed William J. Northen’s victorious campaign for governor and was made president of the Georgia Democratic Convention and chairman of the state Democratic Executive Committee, posts that he held until he ran for governor. In 1892 he was chosen Speaker of the House.

Gubernatorial Career

Atkinson accomplished his startling coup d’état in 1894, first by battling the nomination away from an aging Civil War (1861-65) hero—Confederate general Clement Evans—who was put forward as a candidate by the Bourbons. He then overcame Populist candidate and Atlanta lawyer James K. Hines in the general election, a bitter and contested race that represents the strongest campaign for governor ever mounted by the Georgia People’s Party. Atkinson’s overwhelming reelection in 1896 over another Populist candidate—Seaborn Wright of Rome—marked the end of the Populists as a serious threat to the Democrats in statewide elections.

Atkinson was a hardworking and visionary reformist governor who labored during an era when national issues dominated state politics and statehouses were filled with mediocre men of the status quo. Indeed, one Chicago newspaper called the 1897 Georgia assembly the most incompetent in history. These difficulties also cost Atkinson the race for the U.S. Senate seat given up by John B. Gordon in 1896, which was won by Alexander S. Clay.

As governor, Atkinson often supported principled positions that sought to aid the disfranchised and squelch localized mob rule. He repeatedly condemned lynching, and though his efforts had little practical success against local indifference and racist opposition, his sustained pressure on legislators did produce laws that strengthened sheriffs’ powers and toughened legal penalties for inciting or participating in mob violence. Atkinson also tirelessly advocated reform of the convict lease system, and though limited by the opposition of influential men who profited from the practice, brought about the establishment of a prison commission to oversee the treatment of inmates and to address the system’s most flagrant abuses.

In a period when Georgia’s white-supremacist political parties often shamelessly manipulated or bought votes by African Americans, Atkinson treated Black constituents fairly and endeavored not only to improve their educational facilities and opportunities but also to protect their rights as citizens. In 1896 Atkinson acted where the state supreme court would not, pardoning an innocent Black man, Adolphus Duncan, who had been twice wrongly convicted of and sentenced to die for the rape of a white Atlanta woman. Detractors accused Atkinson of pandering to Black voters.

Other notable actions as governor included the hiring of the first female salaried employee at the state capitol, stricter accounting of election-campaign spending, and measures designed to bring more investment into the state. Although his attempts to attract New England manufacturers to Georgia were not as successful as he had hoped, the governor managed to increase the state’s appeal to outside investors by decreasing the public debt and improving state finances. In biographer Mauriel Shipp’s assessment, “Atkinson’s attempt to correct the outdated evils of Georgia made him a reformer. His support of the helpless man, the lowly negro, and the convict made him a humanitarian. His advocacy of decentralized government and his promotion of education proclaimed him a disciple of Jefferson.”

In late 1898 Atkinson returned to his law practice in Newnan, but his opportunity to enjoy life after public office was unexpectedly brief. Traveling on business in Florida the following May, Atkinson contracted dysentery and died of complications from the illness on August 8, 1899, at the age of forty-four. He was buried at Oak Hill Cemetery in Newnan.