In the court case Worcester v. Georgia, the U.S. Supreme Court held in 1832 that the Cherokee Indians constituted a nation holding distinct sovereign powers. Although the decision became the foundation of the principle of tribal sovereignty in the twentieth century, it did not protect the Cherokees from being removed from their ancestral homeland in the Southeast.

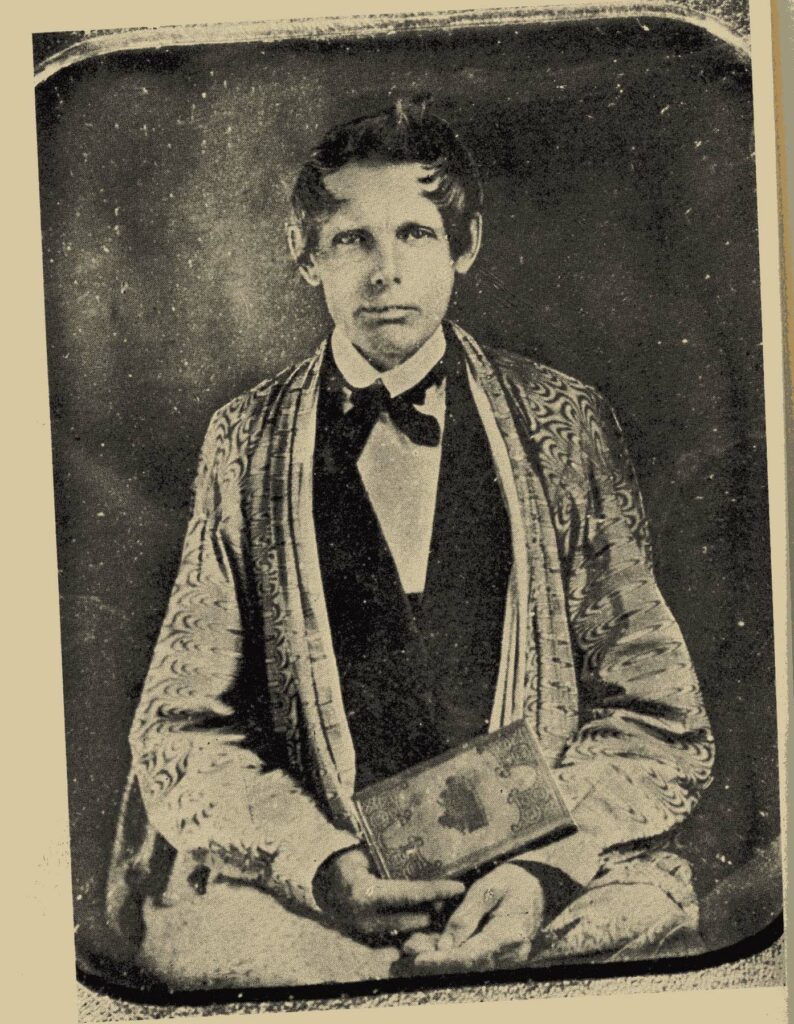

Photograph from Cherokee Messenger, by Althea Bass

In the 1820s and 1830s Georgia conducted a relentless campaign to remove the Cherokees, who held territory within the borders of Georgia, North Carolina, Alabama, and Tennessee at the time. In 1827 the Cherokees established a constitutional government. The Cherokees were not only restructuring their government but also declaring to the American public that they were a sovereign nation that could not be removed without their consent. An infuriated Georgia legislature responded by purporting to extend its jurisdiction over the Cherokees living in the state’s declared boundaries. The state annexed the Cherokee lands; abolished their government, courts, and laws; and established a process for seizing Cherokee land and distributing it to the state’s white citizens. In 1830 representatives from Georgia and the other southern states pushed through Congress the Indian Removal Act, which gave U.S. president Andrew Jackson the authority to negotiate removal treaties with the Native American tribes.

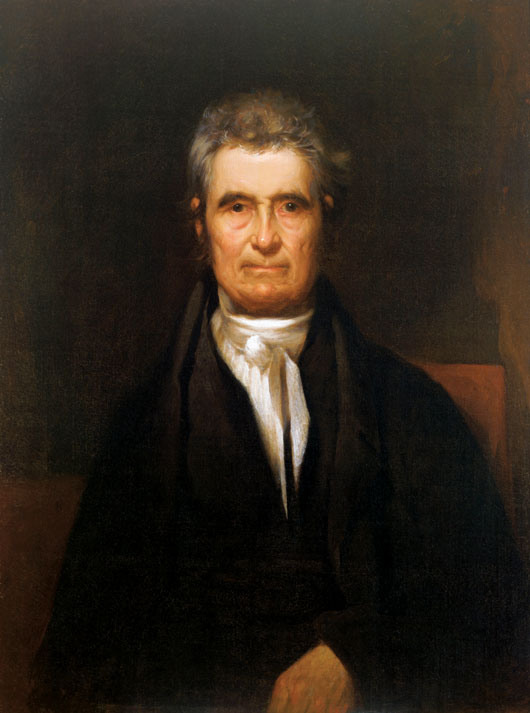

The Cherokees, led by their principal chief, John Ross, refused to remove and instead filed with the U.S. Supreme Court an action challenging the constitutionality of Georgia’s laws. The Cherokees argued that the laws violated their sovereign rights as a nation and illegally intruded into their treaty relationship with the United States. In Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831), the court held that it did not have jurisdiction to strike down Georgia’s laws. In dicta that became particularly important in American Indian law, Chief Justice John Marshall wrote that the Cherokees constituted a “domestic, dependent nation” that existed under the guardianship of the United States.

Photograph by Wikimedia

Samuel Worcester, a native of Vermont, was a minister affiliated with the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM). In 1825 the board sent Worcester to join its Cherokee mission in Brainerd, Tennessee. Two years later the board ordered Worcester to the Cherokee national capital of New Echota, in Georgia. Upon his arrival Worcester began working with Elias Boudinot, the editor of the Cherokee Phoenix, to translate the Bible and other materials into the Cherokee language. Over time Worcester became a close friend of the Cherokee leaders and often advised them about their political and legal rights under the Constitution and federal-Cherokee treaties. Another ABCFM missionary, Elizur Butler, who was also a physician, left New England in the early 1820s, eventually being assigned to the Haweis mission near Rome in 1826.

The Georgia government recognized that Worcester was influential in the Cherokee resistance movement and enacted a law that prohibited “white persons” from residing within the Cherokee Nation without permission from the state. Georgia gave the missionaries until March 1, 1831, to obtain a license of residency or leave the Cherokee Nation. Several missionaries, including Worcester and Butler, decided to challenge the law and refused to leave the state. On March 12, 1831, Georgia authorities arrested Worcester, Butler, and several other missionaries and teachers for violating the new law. A Georgia judge released Worcester when his lawyers argued that he served as federal postmaster at New Echota and was therefore in the Cherokee Nation under authority of the federal government. Governor George R. Gilmer persuaded the United States to relieve Worcester of his postmaster duties and then ordered the missionaries to leave the state.

Three of the missionaries gave up the fight and abandoned their missions. Worcester, Butler, and several of their colleagues remained, and on July 7 the Georgia Guard again arrested Worcester and Butler, and nine other missionaries. After posting bond Worcester returned to New Echota to take care of his wife and daughter, who was seriously ill. Understanding that the Georgia governor would continue to harass him, he left them and relocated to the Brainerd mission. At that point, he received word that his daughter had died. When he returned to New Echota to console his wife, the Georgia Guard arrested him for the third time. Worcester explained why he had returned, and the commander of the guard temporarily released him. In September the missionaries were tried, convicted, and sentenced to four years in prison at hard labor. They were sent to the Georgia penitentiary at Milledgeville.

The missionaries, represented by lawyers hired by the Cherokee Nation, appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. In Worcester v. Georgia, the court struck down Georgia’s extension laws. In the majority opinion Marshall wrote that the Indian nations were “distinct, independent political communities retaining their original natural rights” and that the United States had acknowledged as much in several treaties with the Cherokees. Although it had surrendered sovereign powers in those treaties with the United States, he wrote, the Cherokee Nation remained a separate, sovereign nation with a legitimate title to its national territory. Marshall harshly rebuked Georgia for its actions and declared that the Cherokees possessed the right to live free from the state’s trespasses.

The Cherokee leadership hoped the decision would persuade the federal government to intervene against Georgia and end the talk of removal. Georgia ignored the Supreme Court’s ruling, refused to release the missionaries, and continued to press the federal government to remove the Cherokees. President Jackson did not enforce the decision against the state and instead called on the Cherokees to relocate or fall under Georgia’s jurisdiction. (Although Jackson is widely quoted as saying, “John Marshall has made his decision; now let him enforce it,” his actual words to Brigadier General John Coffee were: “The decision of the supreme court has fell still born, and they find that it cannot coerce Georgia to yield to its mandate.”)

In 1835 a dissident faction of Cherokees signed a removal treaty at the Cherokee capital of New Echota. In 1838 the U.S. Army entered the Cherokee Nation, forcibly gathered almost all of the Cherokees, and marched them to the Indian Territory in present-day Oklahoma, in what became known as the Trail of Tears.

Widespread criticism of Georgia’s imprisonment of the missionaries prompted the state’s new governor, Wilson Lumpkin, to encourage them to accept a pardon. Lumpkin persuaded the Georgia legislature to repeal the law the state had used to convict Worcester and the other missionaries. After intense pressure from the governor, the American Board, and their lawyers, the missionaries gave up on their Cherokee campaign, accepted a pardon, and were released from prison in January 1833.

In several decisions in the latter half of the twentieth century the Supreme Court revived Marshall’s assertion that the Native American tribes possess an inherent form of national sovereignty and the right of self-determination. From that point forward the Worcester decision became the Indian nations’ most powerful weapon against state and local encroachments on their tribal powers.