Georgia was one of the first southern states to build a penitentiary to confine criminals. In 1803, when the city of Milledgeville was chosen to replace Louisville as the capital of Georgia, a square of sixteen acres was set aside for a penitentiary. Governor John Milledge asked the 1804 legislature to establish a penitentiary system “with the view of softening the rigors of our penal code.” Although the legislature did not approve plans for a penitentiary, the subject continued to be on the agendas of successive governors. Under Governor David B. Mitchell (1809-13; 1815-17), the penitentiary finally came to fruition.

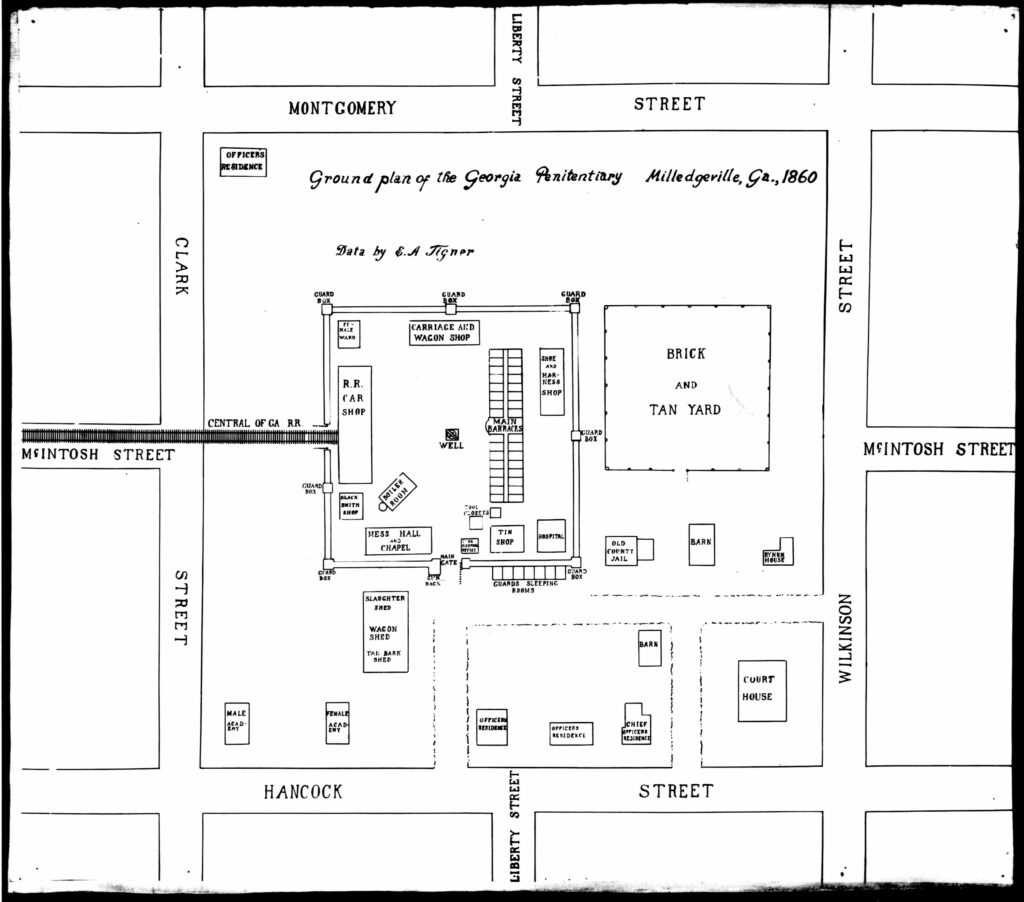

A legislative committee was set up in 1810 to revise Georgia’s penal code and to set up a penitentiary. Construction on the facility began in 1812 and was completed in December 1816. Both the architect and the contractor resided in Milledgeville. The edifice included a wing for male prisoners, prison workshops, and the principal keeper or warden’s house. The penitentiary occupied only a small portion of the square because two academies and the county courthouse shared the site as well. The first prisoner was received in March 1817.

During the early nineteenth century Georgians came to believe that criminals could be reformed if they were confined in a penitentiary. It was believed that criminals should be removed from all association with society so that they would be able to contemplate their actions and repent. People believed that while a troublemaker might have scoffed at the traditional idea of branding or whipping as punishment, “the prospect of confinement in the penitentiary . . . would put fear in his heart.” Georgia followed the examples of early penal reform in Pennsylvania as a model.

The penitentiary was governed by a board of inspectors. The board, composed of nine men who were appointed each year by the General Assembly, was responsible for appointing a principal keeper, a turnkey, and one deputy for every ten convicts. The turnkey was in charge of locking and unlocking doors when inmates were put in and out of cells. Two members of the board were required to visit the penitentiary twice a week. Food for the inmates consisted of bread, Indian meal, and a daily ration of meat such as pork. No liquor was allowed.

Officials promised that the penitentiary would “perform miracles in the rehabilitation of lawbreakers.” Reformers believed that prison shops would provide convicts with useful vocational training while producing revenue for the state. Prisoners were required to do labor of the “hardest and most servile kind,” consistent with their sex, age, health, and ability. The original regulations required that prisoners work every day except Sunday for eight to ten hours. Male prisoners engaged in many types of industry while they were incarcerated. Some of these occupations included tailor, blacksmith, wagon and cart maker, cabinetmaker, shoemaker, glassmaker, and saddle and harness maker. Local tradesmen complained that prison manufacturing led to competition with “regular and honest mechanics” in the town.

Courtesy of Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia Libraries.

Throughout the history of the institution there were relatively few female prisoners. Original legislation for the penitentiary called for a separate wing for women. Although many of the principal keepers urged legislators to appropriate funds for this purpose, the state never made provisions for females. The few women incarcerated there were housed in one room on the second floor near the kitchen. They typically did sewing and similar work.

Many different types of prisoners were confined in the penitentiary. In 1831 two northern missionaries named Samuel Worcester and Elizur Butler served two years of hard labor in the penitentiary. An 1830 law forbade any white person except those specially licensed by the governor to reside among the Cherokees. When Worcester and Butler refused to leave the territory, they were arrested and sent to the penitentiary in Milledgeville. In 1832 Worcester and Butler appealed their case, Worcester v. Georgia , to the U.S. Supreme Court. Their main objective was not to obtain their release but to win a declaration from the court that Georgia’s jurisdiction over the Cherokee land was unconstitutional. The court did indeed rule that Georgia’s 1830 act was a violation of the Constitution and that the Cherokee were an independent and sovereign nation. Nonetheless, U.S. president Andrew Jackson refused to enforce the court’s decision, and Worcester and Butler remained in the penitentiary. Governor Wilson Lumpkin released them a year later.

The penitentiary attracted a great deal of attention and excitement after its construction. Many people saw the new penitentiary as “the harbinger of order and peace” and expected a tremendous change in the behavior and attitudes of the convicts. Not all of Georgia’s leading citizens, however, were supporters of the penitentiary, and throughout its existence there were numerous attempts to abolish it. Some local citizens thought the penitentiary was located too close to the governor’s mansion and local businesses. Others were convinced that the penitentiary would not succeed in reforming criminals and thought the state should impose harsher penalties. One Milledgeville resident referred to the penitentiary as “both a curse and an eyesore,” and another called it a “festering sore in the center of town.”

During the Civil War (1861-1865) the penitentiary was used as an armory. Prisoners began manufacturing rifles, bayonets, and other armaments to supply the Confederate armies. With General William T. Sherman approaching Milledgeville in 1864 on the infamous M

After the Civil War the state attempted to rebuild the damaged penitentiary, and prisoners were once again held there. By this time a large majority of the prison population was Black. Provisional Governor Thomas Ruger initiated the convict lease system in May 1868, leasing 100 prisoners to work on the Georgia and Alabama Railroad. By 1869 almost the entire population of the penitentiary had been transferred to Grant, Alexander, and Company to work on the Macon and Brunswick Railroad. The railroad company rather than the state was then responsible for feeding and clothing the convicts. A major reason that Georgia began using the convict lease system was that it was becoming too costly to maintain a penitentiary.

The original penitentiary buildings began to decay from disuse in the 1870s and fell into such disrepair that the acre was cleared for the potential development of commercial enterprises. The square is now home to Georgia College and State University.