On July 7, 1742, English and Spanish forces skirmished on St. Simons Island in an encounter later known as the Battle of Bloody Marsh. This event was the only Spanish attempt to invade Georgia during the War of Jenkins’ Ear, and it resulted in a significant English victory. General James Oglethorpe redeemed his reputation from his defeat at St. Augustine, Florida, two years earlier, and the positive psychological effects upon his troops, settlers, other colonists, and the English populace rallied them to the cause to preserve Georgia.

Image from Wikimedia

Led by Don Manuel de Montiano, governor of St. Augustine, the Spanish organized an invasion of Georgia in mid-June 1742 with approximately 4,500 to 5,000 soldiers. Weather hampered their progress by sea, and Oglethorpe learned of their impending arrival; he prepared the defenses of St. Simons Island accordingly. He established a fort on the island, on a high bluff overlooking the Frederica River, to protect Darien and Savannah from a Spanish invasion. His forces included a mixture of rangers, British regulars, southeastern Indians, and local citizens, but his total forces numbered less than 1,000 men. The Spanish landed on the southern tip of the island during the afternoon and evening of July 5 and used the nearby Fort St. Simons as their headquarters during the campaign.

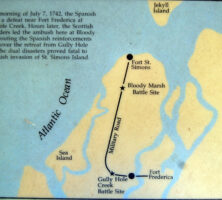

Early on the morning of Wednesday, July 7, several Spanish scouts advanced northward toward Fort Frederica to assess the landscape and plan their attack. They met a body of English rangers at approximately nine o’clock, and the two units exchanged shots. Oglethorpe learned of the engagement, mounted a horse, and galloped to the scene, followed by reinforcements. He charged directly into the Spanish line, which scattered when the additional forces arrived. Oglethorpe posted a detachment to defend his position and returned to Frederica to prevent another Spanish landing on the northern coast and to recruit more men.

Photograph by Forrest Shropshire

During midafternoon of the same day, the Spanish sent more troops into the region, and the English forces fired upon them from behind the heavy cover of brush in the surrounding marshes. This ambush, coupled with mass confusion within the smoke-filled swamp, resulted in another Spanish defeat despite Oglethorpe’s absence. This second engagement earned its name the Battle of Bloody Marsh from its location rather than from the number of casualties, which were minimal, especially on the English side (about fifty men, mostly Spanish, were killed). The Spanish left the island on July 13.

Photograph by Jud McCranie, Wikimedia

The consequences of this battle were considerable. The brave stand by Oglethorpe’s men restored their confidence because the Spanish no longer seemed indestructible. Conversely, the morale of the Spanish suffered greatly, resulting in retreat and a reluctance to undertake future campaigns into the region. Oglethorpe’s daring actions and use of effective tactics reestablished his military leadership. On an imperial level, citizens throughout the colonies and in the homeland rejoiced at the repulse of the Spanish invasion of British North America. This decisive English victory represented the last major Spanish offensive into Georgia