The Butlers of South Carolina and Philadelphia owned extensive plantations in the Sea Islands of Georgia, where hundreds of enslaved workers labored to grow the rice and cotton on which the family’s wealth was based.

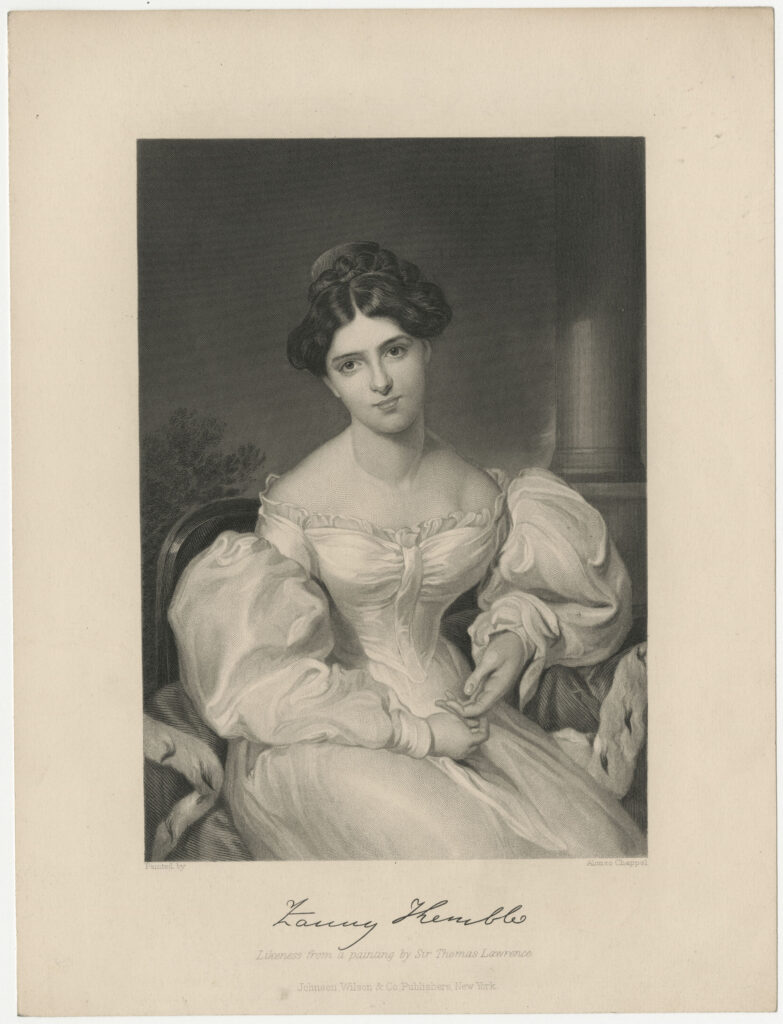

The most prominent members of the family were the patriarch, Pierce Butler (1744-1822), who amassed the fortune; his grandson Pierce Mease Butler (1806-67); and the latter’s wife, Fanny Kemble (1809-93), author of the influential antislavery book Journal of a Residence on a Georgian Plantation in 1838-1839 (1863).

The elder Pierce Butler, born the third son of an Irish baronet, could make no claim to title or family fortune and so determined to make his own way in the army. He became a major in His Majesty’s Twenty-ninth Regiment, and in 1767 he came to the colonies, where he met and married a wealthy South Carolina planter’s daughter, Mary Middleton. Though never the fiercest patriot, he sided with the colonials in the Revolution, selling his army commission and using the proceeds to purchase Hampton Point Plantation on St. Simons Island. In 1787 Butler was appointed a South Carolina delegate to the constitutional convention in Philadelphia, where he demanded and secured protections for slavery in the founding document of the United States. By 1793 he was the absentee master of a personal empire—more than 500 enslaved workers toiling in 800 acres of cotton and 300 acres of rice—that enabled him to purchase two homes in Philadelphia and live in palatial comfort the rest of his life.

As with many patriarchs, Pierce Butler’s greatest dilemma proved to be the problem of succession. Butler considered himself a devoted father, but his devotion could be often compulsive and controlling. Writing to his son Thomas, Butler noted, “If your Class shoud [sic ] leave You behind, or if You shoud be Last in the Class . . . I shall wish Myself under Ground.” Thomas was not yet ten years old. Still, the boy probably found the prospect of his father’s dying of shame a trifle more comforting than those held out by other of his father’s happy missives, “I would rather see you dead than have you Fear anything. It is better to die once than many times. The Brave never die but once—The Coward dies daily.”

In certain respects, Pierce Butler did not die at all, ruling his family from beyond the grave. His will, a byzantine affair, cut some children out altogether and passed his Georgia estate directly to his grandsons—providing that they changed their name to Butler. All eventually did, lured on by the awful majesty of the major’s legacy. Ironically, one of these grandsons, his namesake, Pierce Mease Butler (born Butler Mease), was a model of the weaknesses his grandfather despised. Devoid of business sense and dissolute in his personal habits, Pierce was captivated by the English actress Fanny Kemble and induced her to marry, with famously disastrous consequences. In the winter of 1838-39, the newlyweds traveled to the family’s vast holdings on the Sea Islands, where Fanny was struck by the awfulness of slavery. She eventually published an account of her impressions to much acclaim, but this was long after she and Pierce had been through a nasty divorce that left her financially weakened and without the custody of their two daughters.

The divorce did little to sober Pierce; by 1859 he had made such a wreck of his finances that he decided to sell off some of his “property.” On March 2 and 3, 1859, the largest sale of human beings in the history of the United States took place on a rainy racetrack in Savannah. Capturing the event for the New York Tribune, Mortimer Thomson, writing under the pen name Q. K. Philander Doesticks, noted, “On the faces of all [the enslaved people] was an expression of heavy grief; some appeared to be resigned . . . some sat brooding moodily over their sorrows, . . . their bodies rocking to and fro with a restless motion that was never stilled.” When the sale was complete, 429 men, women, and children had been auctioned to the highest bidder, netting more than $300,000 and restoring Pierce Butler to his accustomed affluence.

After the Civil War (1861-65) the Butlers tried and failed, as did other Sea Island families, to plant without enslaved workers. In 1867 Pierce Butler, unable to coax another redemption from his inheritance, died of malaria. His Confederate daughter, Frances Kemble Butler Leigh, picked up where he left off but gave up after a decade; she captured the attempt in her own journal—an odd companion to her mother’s—Ten Years on a Georgia Plantation Since the War (1883). What was left of the estate passed to Leigh’s nephew, Owen Wister, author of The Virginian (1902). Wister then sold the last of the Altamaha lands in 1923 for about $25,000, a fifteenth of what it was worth a hundred years before (in absolute dollars).