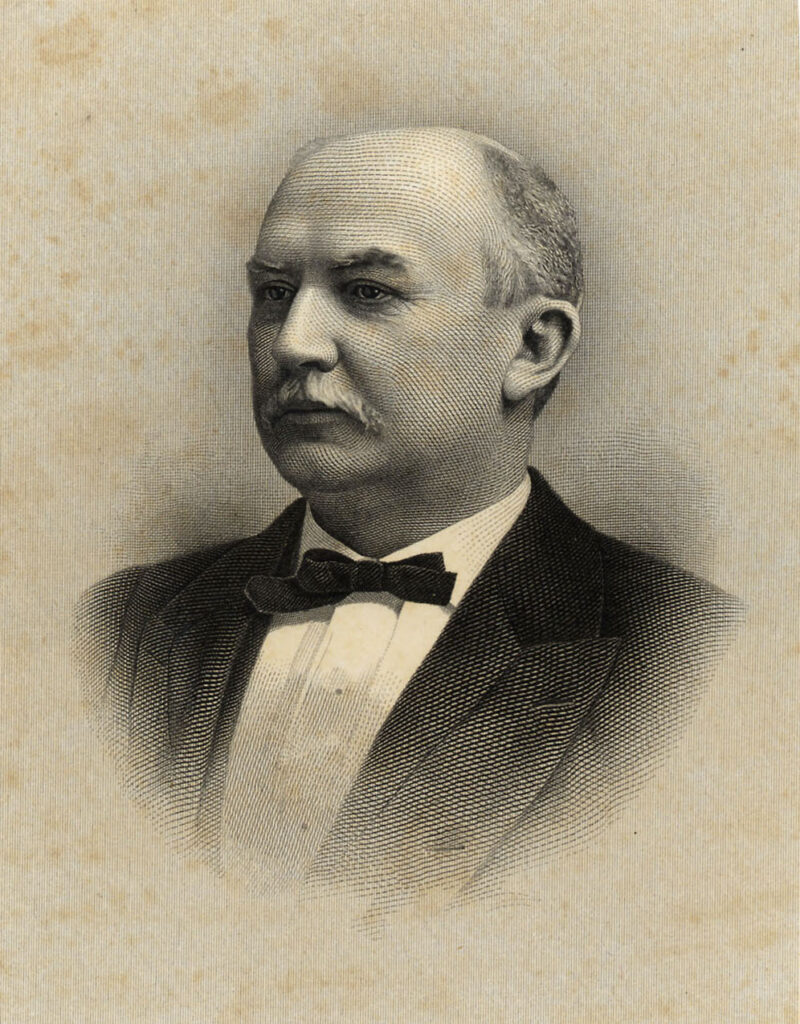

Charles Crisp was a Confederate soldier and Georgia jurist before serving as a U.S. congressman. He was elected Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives in 1891 and served in that role until 1895. Crisp County, created in south Georgia in 1905, was named for him.

From Memorial Addresses on the Life and Character of Charles Frederick Crisp

Charles Frederick Crisp was born in Sheffield, England, on January 29, 1845, to actors Eliza and William Crisp. The Crisps were naturalized American citizens who were visiting their native land at the time of their son’s birth. Initially the couple worked as touring actors in America but eventually made their home in Georgia. Crisp’s father was manager of a theater in Savannah for seven years beginning in about 1853, and Charles received his early education there.

In 1861 Charles Crisp and his brother Harry enlisted in the Confederate army. Charles rose to the rank of lieutenant in the Tenth Virginia Infantry before being captured in May 1864. At the end of the Civil War (1861-65) Crisp returned to Georgia, settling in Ellaville in Schley County. After his admission to the Georgia bar in 1866, Crisp opened a private law practice in Ellaville. He married Clara Belle Burton there in 1867, and the couple had four children.

Crisp moved to Americus in 1873 and was appointed solicitor general of the Southwestern Judicial Circuit. Next appointed superior-court judge in the same circuit in 1877, he was twice reappointed to the same position. Crisp resigned from the bench in 1882 to accept a nomination as Democratic candidate for the Third Congressional District. He was elected to the U.S. Congress and in 1883 took his seat, which he held until his death.

In Congress, Crisp quickly became a leader of his party, notably during the debate for passage of the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887, which was intended to regulate railroad monopolies for the benefit of farmers and small businessmen.

When the Democrats retook control of the House of Representatives after the election of 1890, Crisp was elected Speaker, the lone Georgian to hold the position between Howell Cobb (1849-51) and Newt Gingrich (1995-99). Among the Georgia delegation, only the Populist Thomas E. Watson opposed Crisp’s selection. Assuming his post in 1891, Crisp undid many of the partisan reforms effected by his predecessor, Republican Thomas B. “Czar” Reed, and strengthened the powers of his office by retaining for himself the chairmanship of the Committee on Rules. This committee virtually dictated the legislative business of the House by controlling which bills reached the floor for debate. Republicans won back the House in the election of 1894, and Crisp vacated the speakership after two terms. He became the leader of the minority in the next session of Congress and engaged in many battles with Reed, who was reinstated as Speaker.

Crisp had declined an appointment to the U.S. Senate in 1894, but in 1896 he announced his candidacy for the seat vacated by the retirement of Senator John B. Gordon. Crisp had been sick during the summer, but in the fall he stumped across the state, debating with fellow Georgian Hoke Smith, then secretary of the interior under U.S. president Grover Cleveland. Smith was not a candidate but spoke for the Cleveland policy of remaining on the “gold standard,” that is, retaining gold as the primary monetary metal of the United States. Crisp campaigned vigorously and won a statewide popular primary because of his support for “free coinage of silver” (or the expanded availability of silver money). But shortly before the Georgia legislature convened to elect him to the Senate, Crisp died suddenly, though not unexpectedly, in Atlanta on October 23, 1896, at the age of fifty-one. He was buried in Oak Grove Cemetery. His son, Charles Robert Crisp, was appointed to complete his unexpired congressional term.

Crisp was a typical conservative Southern Democrat when he first arrived in Washington, D.C. Over the years, however, he came to support many of the causes important to the rural agrarian population he represented, including the regulation of railroad monopolies, low tariffs on imported goods, and cheap currency. In effect he became a modified Populist, as, for example, when he broke with Southern Democrats in his support for the repeal of the Sherman Silver Purchase Act in 1893. Robert Preston Brooks, in the Dictionary of American Biography, calls Crisp “among the two or three ablest Georgia congressmen” in the seventy years following the Civil War. If he had lived to take a seat in the Senate, Crisp may well have had an even greater influence on national politics.