Charles Weltner was a moderate and respected leader in Georgia law and politics. As a U.S. congressman, he was an outspoken opponent of segregation. Weltner also served as associate justice of the Supreme Court of Georgia.

Charles Longstreet Weltner was born in Atlanta on December 17, 1927, to Sally Hull and Philip Weltner, the chancellor of the University System of Georgia and later president of Oglethorpe University in Atlanta. He was the great-great-grandson of Joseph Henry Lumpkin, the first chief justice of Georgia’s supreme court, and the great-grandson of Thomas R. R. Cobb, a Confederate general.

In 1948 Weltner received a bachelor’s degree from Oglethorpe University and in 1950 received a law degree from Columbia University in New York City. After serving as a first lieutenant in the U.S. Army for two years, Weltner practiced law in Atlanta for a decade before entering politics. An advocate in the 1950s for racial equality he often spoke out against the violence and repression caused by segregation.

Weltner served as a U.S. congressman from Atlanta’s Fifth District from 1963 to 1967, one of the South’s most tumultuous periods. During his first year in office, he openly supported the 1954 Supreme Court ruling outlawing segregation in the public schools. On July 2, 1964, Weltner cast an affirmative vote for the Civil Rights Act, declaring that “we in the South face some difficult decisions. We can offer resistance and defiance… or we can acknowledge this measure as the law of the land.” In 1964 Newsweek declared him a “prototype of the articulate young congressman—the 'new breed’ on whom so many Southern moderates stake their hopes for the future.” A year earlier, Weltner had become the first southern politician to condemn his colleagues for standing mute after the bombing of a Birmingham, Alabama, church that killed four young African American girls. He also chaired the 1964-65 House Committee on Un-American Activities’ investigation of the Ku Klux Klan.

On October 3, 1966, Weltner made a national name for himself when he chose to give up his seat in Congress rather than support Lester Maddox, a segregationist who opposed the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act. Weltner refused to sign a Georgia Democratic Party loyalty oath that would have required him to support Maddox’s gubernatorial campaign. In his resignation speech, he declared, “I love the Congress, but I will give up my office before I give up my principles….I cannot compromise with hate. I cannot vote for Lester Maddox.” Weltner failed to regain the seat in 1968. Five years later, Weltner launched an unsuccessful bid for mayor of Atlanta, losing to Maynard Jackson.

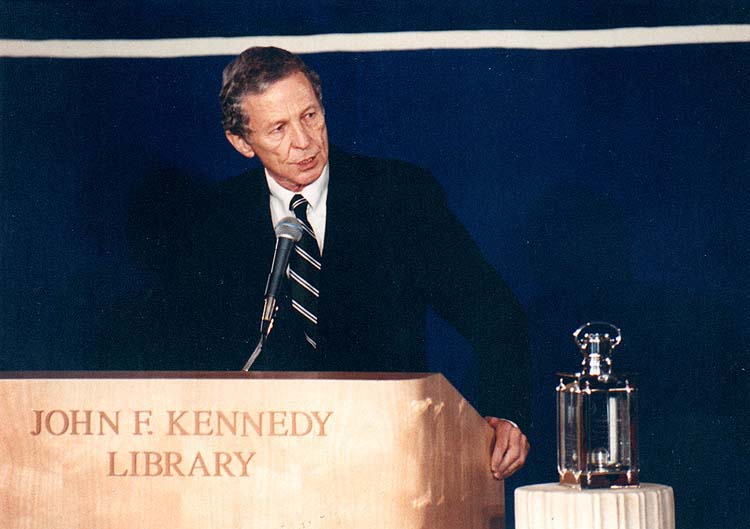

After leaving politics, Weltner enjoyed a successful career in the judicial system, first serving as a judge in the Fulton County Superior Court from 1976 to 1981 and then serving as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of Georgia from 1981 to 1992. He was active on the bench, supporting legal and political reform. In 1991 he became the second individual to be honored with the John F. Kennedy Profile in Courage Award. The next year Weltner was given the Shining Light Award by the Atlanta Gas Light Company and WSB radio.

Weltner married Betty Jean Center in 1950, and they had four children. In 1972 he married Juanita McKinney Lynn, and in 1978 he married Anne Fitten Glenn, with whom he had two children. They were married until his death in Atlanta on August 31, 1992.