In 1838 and 1839 U.S. troops, prompted by the state of Georgia, expelled the Cherokee Indians from their ancestral homeland in the Southeast and removed them to the Indian Territory in what is now Oklahoma. The removal of the Cherokees was a product of the demand for arable land during the rampant growth of cotton agriculture in the Southeast, the discovery of gold on Cherokee land, and the racial prejudice that many white southerners harbored toward American Indians.

Courtesy of Woolaroc Museum, Bartlesville, Oklahoma

Origins of Removal Policy

By the nineteenth century the Cherokees had lived in the interior Southeast, including north Georgia, for hundreds of years. Settlers of European ancestry began moving into Cherokee territory in the early eighteenth century; from that point forward, the colonial governments in the area began demanding that the Cherokees cede their territory. By the end of the Revolutionary War (1775-83), the Cherokees had surrendered more than half of their original territory to state and federal governments.

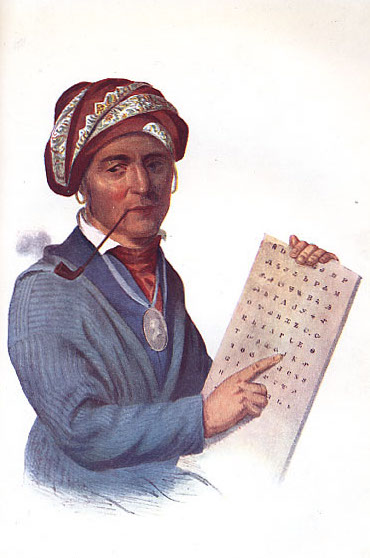

In the late 1780s U.S. officials began to urge the Cherokees to abandon hunting and their traditional ways of life and to instead learn how to live, worship, and farm like Christian American yeomen. Many Cherokees embraced this “civilization program.” The Cherokees established a court system, formally abandoned the law of blood revenge, and adopted a republican government. A Cherokee man named Sequoyah created the Cherokee syllabary, which enabled the Cherokees to read, write, record their laws, and publish newspapers in their own language.

Despite these efforts, white people in Georgia and other southern states that abutted the Cherokee Nation refused to accept the Cherokee people as social equals and urged their political representatives to seize the Cherokees’ land. The purchase of the Louisiana Territory from France in 1803 gave U.S. president Thomas Jefferson an opportunity to implement an idea he had contemplated for many years—the relocation of the eastern tribes beyond the Mississippi River. There, Jefferson suggested, Native Americans could acculturate at their own pace, retain their autonomy, and live free from the trespasses of American settlers. Although most Cherokees rejected Jefferson’s entreaties, small groups moved west to the Arkansas River area in 1810 and 1817-19.

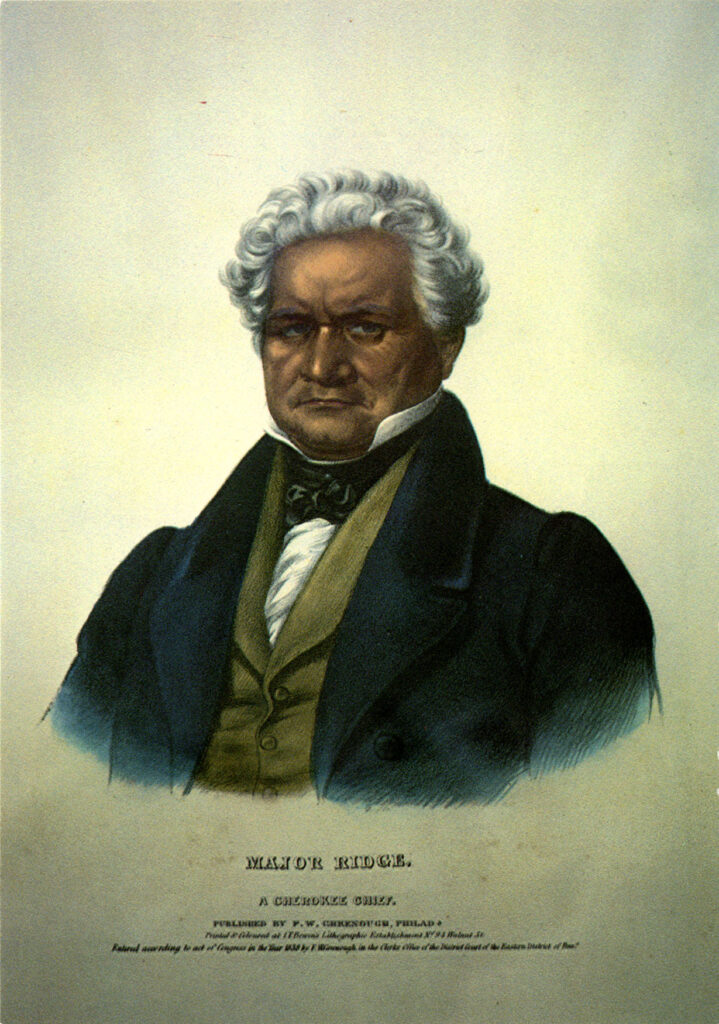

From The Indian Tribes of North America, by T. L. McKenney and J. Hall

After the War of 1812 (1812-15), prominent southerners like General Andrew Jackson called for the United States to end what he called the “absurdity” of negotiating with the Indian tribes as sovereign nations. From that point forward, Georgia politicians, including George Troup, George R. Gilmer, and Wilson Lumpkin, increasingly raised the pressure on the federal government to fulfill the Compact of 1802, in which the federal government had agreed to extinguish the Indian land title and remove the Cherokees from the state.

Cherokee Resistance

The Cherokee government maintained that they constituted a sovereign nation independent of the American state and federal governments. As evidence, Cherokee leaders pointed to the Treaty of Hopewell (1785), which established borders between the United States and the Cherokee Nation, offered the Cherokees the right to send a “deputy” to Congress, and made American settlers in Cherokee territory subject to Cherokee law.

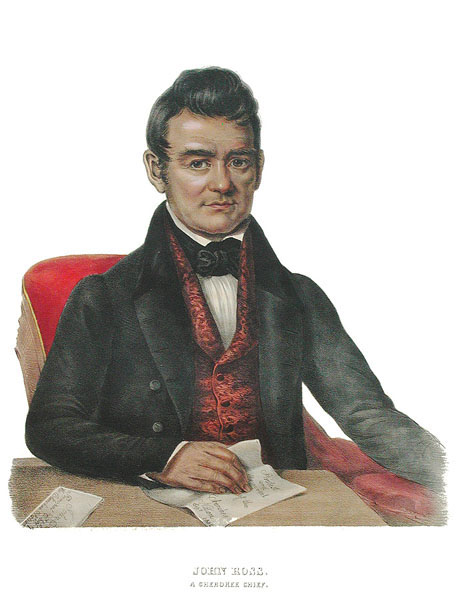

The Cherokee government , especially its principal chief, John Ross, took steps to protect its national territory. Ross joined Charles Hicks and Major Ridge in the “Cherokee Triumvirate” and received recognition for his efforts in negotiating the Treaty of 1819. He then continued his work by making legal moves for the Cherokees as president of the constitutional convention. In 1825 New Echota, the Cherokee capital, was established near present-day Calhoun, Georgia. The Cherokee National Council advised the United States that it would refuse future cession requests and enacted a law prohibiting the sale of national land upon penalty of death. In 1827 the Cherokees adopted a written constitution, an act that further antagonized removal proponents in Georgia.

Print by Charles Bird King. From History of the Indian Tribes of North America, by T. McKenney and J. Hall

Between 1827 and 1831 the Georgia legislature extended the state’s jurisdiction over Cherokee territory, passed laws purporting to abolish the Cherokees’ laws and government, and set in motion a process to seize the Cherokees’ lands, divide it into parcels, and offer the parcels in a lottery to white Georgians. In 1828 Andrew Jackson was elected president of the United States, and he immediately declared the removal of eastern tribes a national objective. In 1830 Congress passed the Indian Removal Act, which authorized the president to negotiate removal treaties.

Artwork by George I. Parrish Jr. Courtesy of Cindy Parrish, Maryville,TN

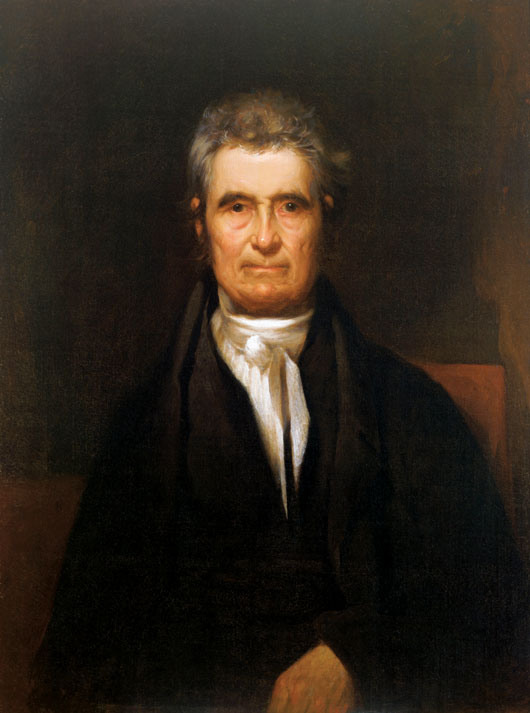

With Congress and the president pursuing a removal policy, the Cherokee Nation, led by John Ross, asked the U.S. Supreme Court to intervene on its behalf and protect it from Georgia’s trespasses. In Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831), John Marshall, chief justice of the court, wrote that the Cherokees were a “domestic dependent nation” under the protection and tutelage of the United States. The court, however, did not redress the Cherokees’ grievances. A year later, in Worcester v. Georgia, the Supreme Court declared that Georgia had violated the Cherokee Nation’s sovereign status and wrongfully intruded into its special treaty relationship with the United States. President Jackson, however, refused to enforce the decision and continued to pressure the Cherokees to leave the Southeast.

The Trail of Tears

The Cherokee Nation subsequently divided between those who wanted to continue to resist the removal pressure and a “Treaty Party” that wanted to surrender and depart for the West. In 1835 the latter group, led by Major Ridge, John Ridge, and Elias Boudinot, signed the Treaty of New Echota at the Cherokee capital without the authority of Principal Chief Ross or the Cherokee government. The treaty required the Cherokee Nation to exchange its national lands for a parcel in the “Indian Territory” and to relocate there within two years. This parcel, set aside by Congress in 1834, was located in what is now Oklahoma. The federal government promised to remit $5 million to the Cherokee Nation, compensate individuals for their buildings and fixtures, and pay for the costs of relocation and acclimation. The United States also promised to honor the title of the Cherokee Nation’s new land, respect its political autonomy, and protect its tribe from future trespasses. Even though it was completed without the sanction of the Cherokee national government, the U.S. Senate ratified the treaty by a margin of one vote.

After Major Ridge signed away Cherokee land, Chief Ross gathered 16,000 Cherokee signatures against the treaty, proving that the majority of the tribe was not in agreement. The Cherokee government protested the legality of the treaty until 1838, when U.S. president Martin Van Buren ordered the U.S. Army into the Cherokee Nation. The soldiers rounded up as many Cherokees as they could into temporary stockades and subsequently marched the captives, led by John Ross, to the Indian Territory. Scholars estimate that 4,000-5,000 Cherokees, including Ross’s wife, Quatie, died on this “trail where they cried,” commonly known as the Trail of Tears. Once in the Indian Territory, a group of men who had opposed removal attacked and killed the two Ridges and Boudinot for violating the law that prohibited the sale of Cherokee lands. The Cherokees revived their national institutions in the Indian Territory and continued as an independent, self-sufficient nation.

From History of the Indian Tribes of North America, by T. McKenney and J. Hall