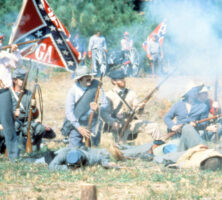

Reenactments of the Civil War (1861-65) are the most popular and widely known form of Civil War public commemoration in Georgia. Reenacting is a loosely organized hobby in which men and women dress as Union or Confederate soldiers or civilians to stage re-creations of Civil War battles, encampments, or marches. The hobby also offers fellowship, fun, and education to its participants and to its audiences. There are perhaps 2,000 active Civil War reenactors in Georgia. Additionally, many of the estimated 35,000 Civil War reenactors in the United States and 3,000 abroad visit Georgia to participate in reenactments.

Courtesy of Gordon L. Jones

Origins of Civil War Reenacting in Georgia

As an organized hobby, Civil War reenacting emerged in the early 1960s during the Civil War centennial. However, the tradition of reenacting battles is much older. Throughout the nineteenth century, town festivals often featured a historical play or pageant in which local residents dressed as Native Americans, early settlers, or soldiers in the Revolutionary War (1775-83) in order to portray the history of their community as they wished it to be remembered. This tradition of historical public performance, which later incorporated scenes from Civil War battles and the Reconstruction era, remained strong well into the twentieth century.

Before the Civil War, militia musters occasionally involved “sham battles,” which were essentially practice maneuvers conducted with blank ammunition. During the Civil War, sham battles were conducted both as military training and as public spectacle. A series of three sham battles took place in the Confederate Army of Tennessee’s winter camp near Dalton in March and April 1864, before a crowd of local residents and the commanders of the army. Volunteers training during theSpanish-American War (1898) camped, drilled, and held sham battles on the battlefield at Chickamauga, though none of these “battles” were intended as historical re-creations. The U.S. Army continued to use sham battles as part of its military training through the 1940s.

In the 1880s, reflecting renewed public curiosity about the war, many sham battles were conducted purely as entertainment. Although these sham battles were usually not attempts to re-create specific Civil War battles, they were conducted with strong undertones of both sectional pride and national unity. An estimated 20,000 people attended opening events of the Piedmont Exposition in Atlanta (held two years after the well-known Piedmont Exposition of 1887), where on October 16, 1889, a sham battle was staged by 10 Georgia militia companies, about 100 members of the Confederate Veteran

Courtesy of Clayton County Convention and Visitor's Bureau

Civil War veteran reunions were often marked by military-style tented encampments and were occasionally accompanied by a sham battle or historical pageant. However, there is no evidence that Union and Confederate veterans ever actually reenacted a battle against each other; to have done so would have violated the spirit of national reconciliation inherent in these events.

In the 1930s Army National Guard units, U.S. Marines, and military school cadets began to stage what could be called the first true Civil War reenactments. These public performances used contemporary military formations, uniforms, and weapons to re-create actual battles on or near the anniversary dates of the battles. During the week of September 16-25, 1938, the seventy-fifth anniversary of the Battle of Chickamauga was marked by parades, races, fireworks, a horse show, and a historical pageant entitled “Drums of Dixie.” On September 19, 700 soldiers from nearby Fort Oglethorpe reenacted the Battle of Chickamauga on Dyer Field, in the middle of the national park.

Reenacting during the Civil War Centennial

In the early 1960s middle-class affluence combined with commercialism, automobile travel, and the 100th anniversary of the Civil War to once again reinvigorate interest in the war and in re-creating its battles. On July 21-22, 1961, the National Park Service and the Civil War Centennial Commission helped sponsor a reenactment of the First Battle of Manassas (known in the North as the Battle of Bull Run) on the original ground at the Manassas National Battlefield Park in Virginia. The reenactment turned out to be a logistical, financial, and public relations nightmare for the organizers. The National Park Service faced unexpected costs, property damage, and legal liabilities as a result of 2,200 participants (including a contingent from Georgia) and around 50,000 spectators crowding into the park each day. The centennial commission faced public criticism for “celebrating” violence and a Confederate victory during a period of intense international tension and the domestic turmoil of the civil rights movement. Both organizations subsequently abandoned any further involvement in Civil War reenactments. As a direct result of this decision, reenactments are today not allowed on any property administered by the National Park Service.

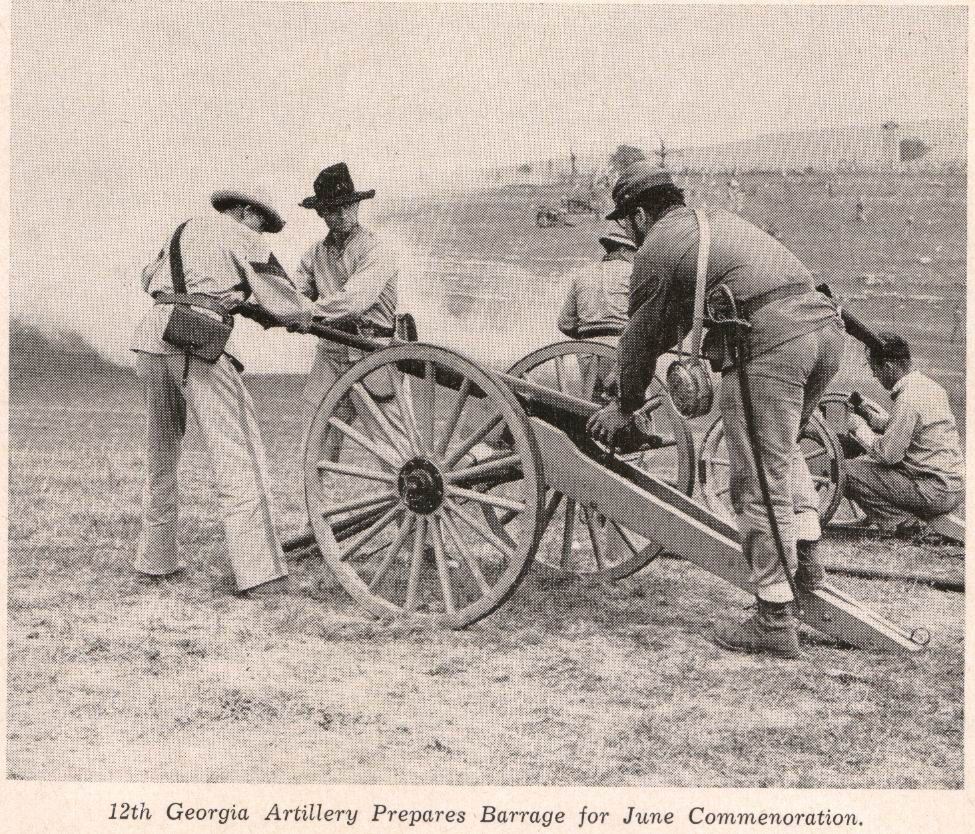

From Centennial Commemoration, Battle of Kennesaw Mountain--June 27, 1864-1964: Official Souvenir Program

Nevertheless, the momentum inspired by the 1961 Manassas reenactment influenced many amateur enthusiasts in the North-South Skirmish Association, a group of black-powder firearms buffs formed in 1950, who soon began forming their own groups devoted specifically to reenacting Civil War battles. In Georgia, small commemorations using amateur costumed participants were held at Milledgeville in 1961 and at Fort Pulaski in 1962 to mark the centennial of the state’s secession from the Union. Similar commemorations marked the centennials of the Andrews Raid in April 1962 and the Battle of Chickamauga in September 1963.

In 1964 the Georgia Civil War Centennial Commission helped to sponsor a series of five reenactments to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the Atlanta campaign. The five battles reenacted were:

—Battle of Resaca (May 16, 1964, on portions of original battlefield)

—Battle of New Hope Church (May 23, 1964, on portions of original battlefield)

—Battle of Kennesaw Mountain (June 27, 1964, on Cobb County farm)

—Battle of Atlanta (July 25, 1964, at Stone Mountain)

—Battle of Jonesboro (August 29, 1964, on farm outside Jonesboro)

The largest of the centennial reenactments in Georgia was the Battle of Kennesaw Mountain, which attracted more than 2,000 participants, including mounted cavalrymen, using cannons, mortars, and wagons. An estimated 7,000 spectators witnessed the event. Unlike the 1961 reenactment at Manassas, in which half the participants were National Guardsmen or military cadets, participants in the 1964 Georgia reenactments were volunteers who made their own uniforms and props; many used original Civil War arms and accoutrements. Thus was Civil War reenacting established as a true organized hobby.

The following year, on July 4, 1965, a small commemorative reenactment event occurred at “Unity Day” in the town of Fitzgerald, chosen for its symbolic value as a site of national reconciliation. Despite genuine efforts to promote North-South reconciliation, the centennial reenactments in Georgia bore a distinctively neo-Confederate flavor. Many participants saw the events as opportunities to advocate for states’ rights, anti-integrationist, and white supremacist agendas. Thus was also established a reputation that still colors the reenacting hobby today.

Civil War Reenacting in the Twenty-first Century

Today the Civil War is not the only conflict simulated by hobbyists, but it is by far the most popular one in Georgia and in the United States. The Revolutionary War, World War I (1917-18), World War II (1941-45), and the Vietnam War (1964-73) are also reenacted; other hobbyists specialize in military and other aspects of the ancient, medieval, and Renaissance eras.

Courtesy of Gordon L. Jones

Civil War reenacting is a decentralized hobby based around small local organizations, or “units,” that usually comprise ten to thirty regular participants. The units are named after actual Civil War regiments, batteries, or other formations. In 2010 there were roughly thirty-five reenacting units in the state portraying Georgia formations. Approximately fifteen of these were included in the Georgia Division Reenactors Association, a statewide umbrella organization founded in 1978. Many Georgia-based units portray either Union or Confederate soldiers. Additionally, units portraying Georgia formations exist in other states, including California and Illinois, as well as abroad.

Civil War reenacting units are often semifraternal organizations with members closely tied to one another by bonds of family, friendship, and a common outlook on their unit’s role within the hobby. Within each unit, leaders are elected and afforded titles of military rank, such as sergeant or lieutenant; these ranks then correspond to leadership positions during a battle-reenactment performance. The average participant attends at least one significant weekend reenactment event per month, plus practice drills, unit meetings, or other informal gatherings.

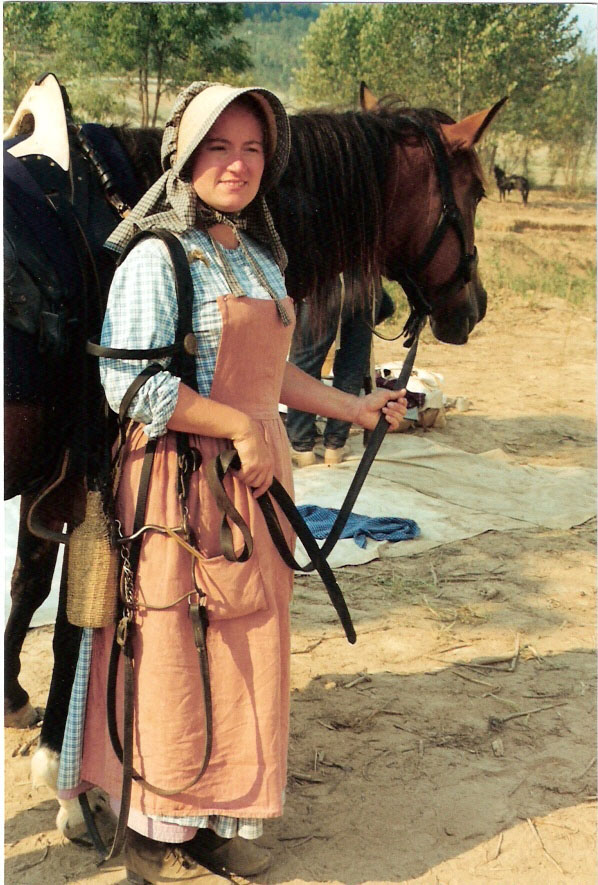

The overwhelming majority of Civil War reenactors are white males in their late thirties or early forties, with middle-class incomes and suburban residences. Most Civil War reenactors express conservative political and social views. Some reenactors are also members of the Sons of Confederate Veterans or the Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War. At the same time, there are increasing numbers of African Americans and women involved in the hobby, in both civilian and soldier roles.

The primary motivation for nearly all Civil War reenactors is a general fascination with history and a specific interest in how ordinary soldiers or civilians lived, dressed, and fought. Much of the pleasure of participation lies in trying to physically re-create the camp and battle experience of Civil War soldiers in all but the most dangerous aspects. Ultimately, one of the goals of participants is to achieve a “period rush,” often defined as a burst of intense emotional connectedness when the Civil War seems”real” and tangible. To that end, reproduction clothing and gear are made to resemble as closely as possible the original items; camp activities, battle formations, and even meals are made to simulate those of the Civil War. Nevertheless, disputes over exactly what constitutes the proper level of authenticity in these respects (and many others) are common among units. The issue of women portraying male soldiers is an especially intense source of controversy within the hobby.

The Civil War reenacting hobby is also marked by friction between those who view participation in the hobby as a means of political expression or of honoring their ancestors, and those who see it as a quest for personal experience and fun. Among Civil War reenactors there is no common consensus on the causes of the war or its relevance today. However, there is a consensus among reenactors that they re-create Civil War battles as a means of educating present-day audiences and honoring soldiers of both sides.

Although Georgia was the site of many Civil War battles, there are relatively few battle reenactments regularly held in the state. The Battle of Tunnel Hill is staged every year on the weekend after Labor Day in conjunction with a town festival in Whitfield County. The Battle of Resaca is held on the third weekend in May on a privately owned portion of the original battlefield in Paulding County. Begun in 1983, it is one of the longest-running annual reenactments in the United States. Other reenactments are held in conjunction with five- or ten-year anniversary dates, such as the 140th or 145th anniversary of the Battle of Chickamauga, which has been held in various locations near the actual battlefield in Walker County. Reenactments of the battles for Atlanta have been held at the Georgia International Horse Park near Conyers and on the Nash Farm Battlefield in Henry County. Occasionally, smaller reenactments, also known as “tacticals” or “immersion events,” take place on private land solely for the benefit and experience of the participants and are not open to the public.

Courtesy of Gordon L. Jones

Nearly all national, state, and locally maintained battlefields, historic sites, and museums in Georgia periodically sponsor Civil War demonstrations or encampments using reenactors as living history interpreters. These events do not involve reenacting but can give visitors a sense of soldiers’ lives and experiences during the war.