The existence of caches of hidden or lost Confederate gold has been the source of numerous Georgia legends. These legends are fueled by the fact that the state was a hub of gold mining, minting, and trading and that, as Richmond, Virginia, fell to Union forces at the end of the Civil War (1861-65), the bulk of the Confederate treasury was brought to Georgia, where much of it disappeared.

The federal Branch Mint at Dahlonega had $23,716 in gold and silver when it was taken over by the Confederate States of America in 1861. During the autumn of 1862, the mint turned $40,000 in gold and silver from New Orleans, Louisiana, into bars for shipment to Augusta. At the same time, Confederate officials seized from the Bank of Louisiana in Columbus $2.3 million in gold and $216,000 in silver specie that had traveled there after New Orleans fell to Union forces.

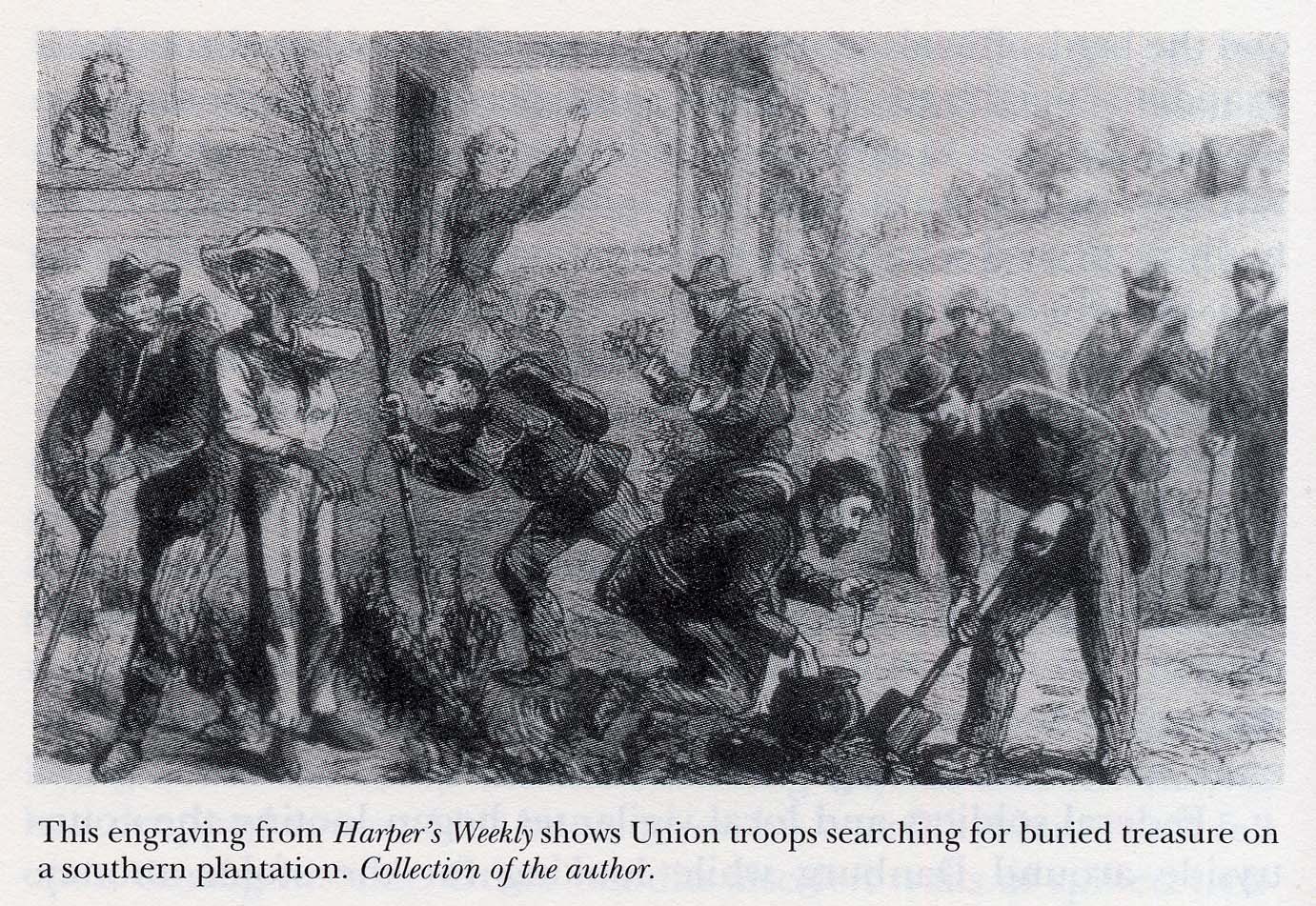

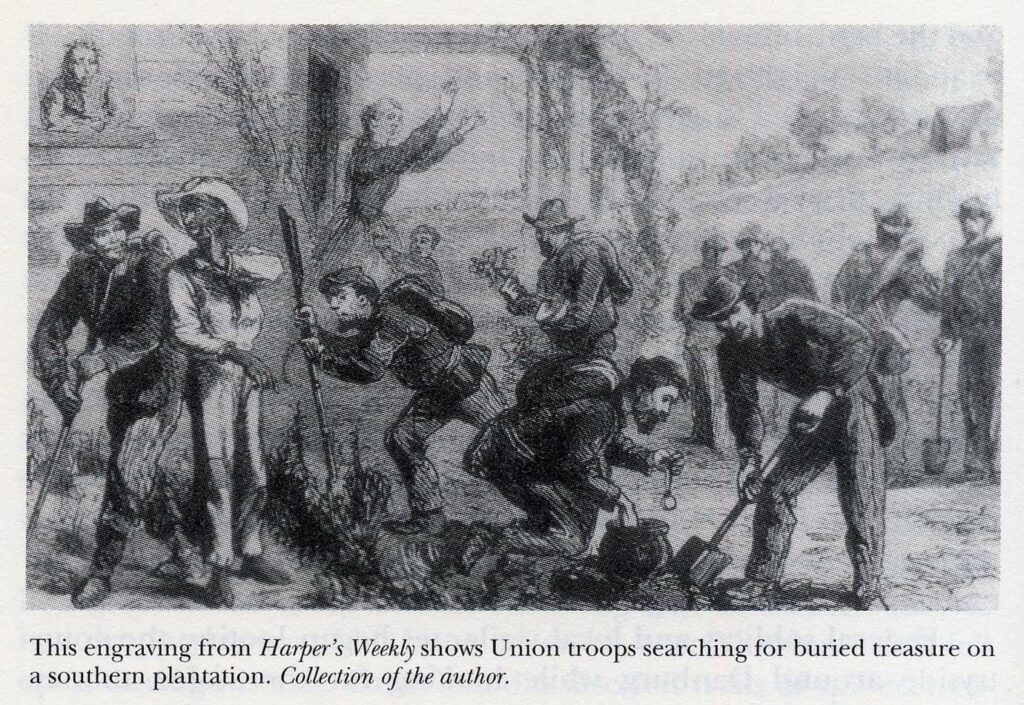

Other specie could be found in Civil War Georgia. Gold from civilians made Macon second only to Richmond as a Confederate depository. By the end of the war, Union general E. L. Molineux in Macon had charge of $275,000 in confiscated gold and silver, including that which Union soldiers plundered from civilians. This total included some $35,000 worth of coins and bullion that had been left for hungry rebels returning home. Molineux also seized $188,000 from the assets of the Central Railroad Bank of Savannah. However, he did not find $200,000 in gold coins from the Georgia State Bank of Savannah that were hidden in Macon. The federal government also confiscated more than $500,000 in assets from the Bank of Tennessee and its branches in Augusta.

The most famous Civil War treasure traveled by wagon to Georgia with Confederate president Jefferson Davis in the last days of the Civil War. This treasure train left Danville, Virginia, on April 6, 1865, with $327,022 in gold and silver coins, as well as bullion, donated jewelry, and even floor sweepings from the Dahlonega mint. Some $450,000 in coins and specie checks (paper money that could be redeemed for metallic coins) that originated with Richmond banks also traveled with the fleeing Confederate government.

Almost all of the Confederate assets were dispersed, to pay soldiers returning home, before the capture of Davis on May 10, 1865, near Irwinville. The remaining funds from the Richmond banks were left in Washington, Georgia. A detachment of Union soldiers set out to divert this specie to a railhead in South Carolina, but on May 24, 1865, bandits in Georgia attacked the wagons, which had stopped for the night at or around the Chennault Plantation in Lincoln County. Of the cache, $251,029 was lost.

Bank officials eventually recovered some $111,000 of the stolen money. Union general Edward A. Wild led a search of the area for more gold and earned notoriety for the arrest and torture of the Chennault family, who Wild believed were hiding gold but who turned out to be innocent. As a consequence, Union general Ulysses S. Grant removed Wild from his command.

The federal government seized the recaptured gold, and litigation over its ownership continued until June 22, 1893, when the U.S. Court of Claims decreed that the claimants on behalf of the by-then-defunct Richmond banks receive $16,987. This amount represented the proportion of the recovered money equal to that of the funds that the banks never loaned to the state of Virginia for the Confederate government but that had also traveled to Georgia in April 1865. The other $78,276 remained the property of the United States.