In the late nineteenth century, fairs and expositions were an important way for cities to attractvisitors and investors who, in an era before radio and television, were eager to see new technological marvels on display. These events provided civic leaders with a showcase to lure visitors, who were urged to come and do business in the host location.

In the years following the Civil War (1861-65), Atlanta’s leaders hosted a series of three “cotton expositions” that were important to the city’s recovery and economic development. These expositions helped Atlanta stake its claim as the center of the New South and helped relieve regional sectionalism that may have been lingering after the Civil War. The great promoter of the first two expositions was Henry W. Grady, the managing editor of the Atlanta Constitution and one of the framers of a new vision for the South and its economy.

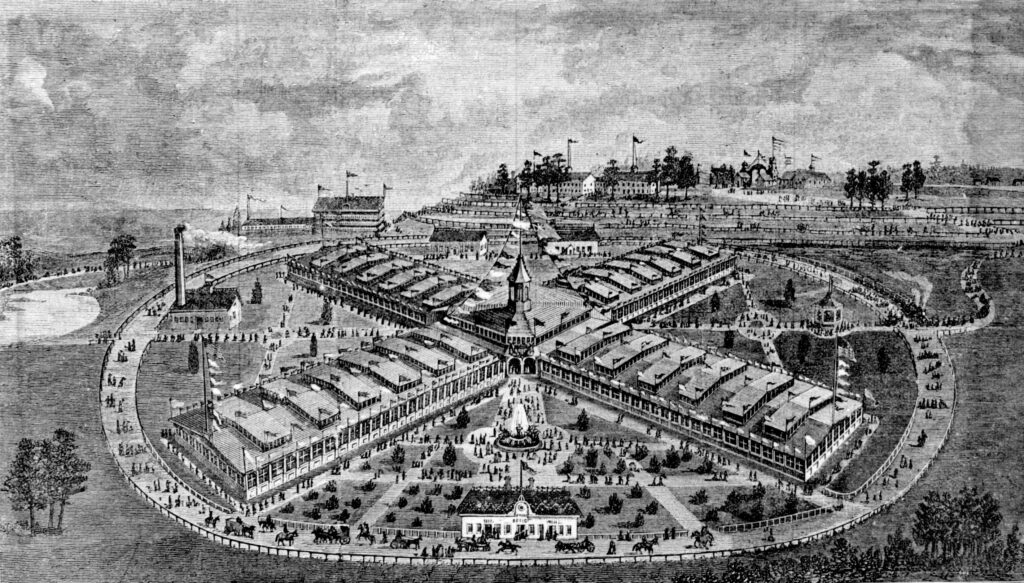

The 1881 International Cotton Exposition

Atlanta held its first exposition, named the International Cotton Exposition, in Oglethorpe Park in 1881. The city then had fewer than 40,000 residents, and the primary sense in which the first exposition was “international” was the display of cotton plants from around the world. Nevertheless, Atlantans were eager to host the 1881 exposition to promote investment and to help the city toward its goal of becoming an industrial center, which was a primary component of Grady’s “New South” concept. Although attendance was lower than expected (fewer than 200,000 in paid attendance during its two-and-a-half-month run), city leaders demonstrated that they could work together to host a major event and that Atlanta was serious about its role in textile production at a time when the North was beginning to grow dissatisfied with the efficiency of southern cotton processing. The exposition displayed new crop planters and cotton seed cleaners, along with a model of Eli Whitney’s original cotton gin, and speakers addressed the crowds about agricultural technology and political reforms.

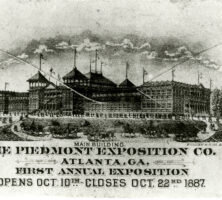

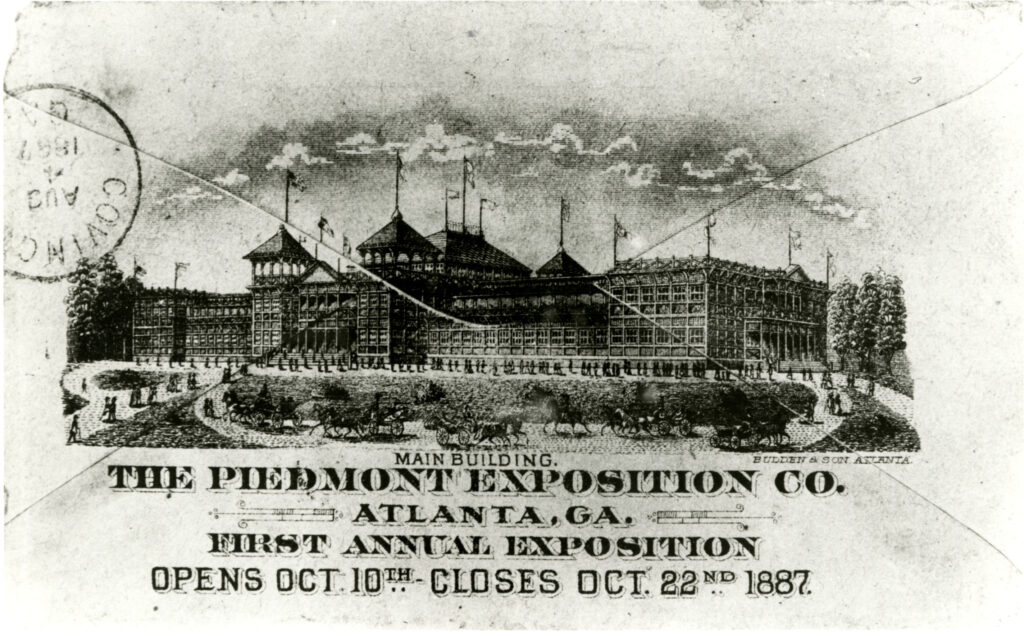

The 1887 Piedmont Exposition

The Piedmont Exposition, held during October 1887, was a more regional event, with nearly 20,000 visitors on opening day. A crowd of more than 50,000 was on hand when Grady introduced the popular U.S. president, Grover Cleveland. After the exposition closed, civic leaders agreed that it had successfully expanded Atlanta’s reputation as a place to visit and to conduct business.

The 1895 Cotton States and International Exposition

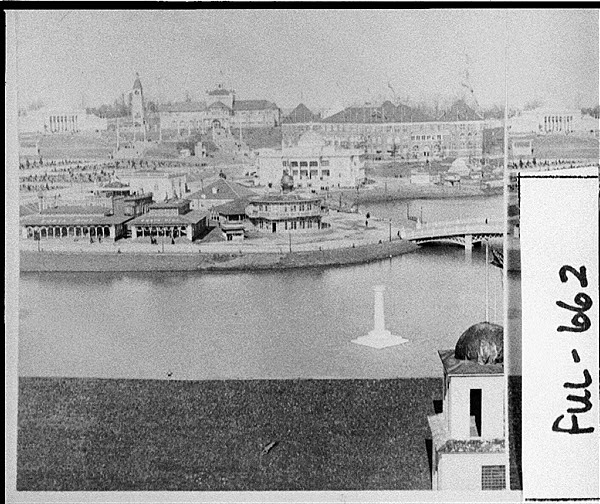

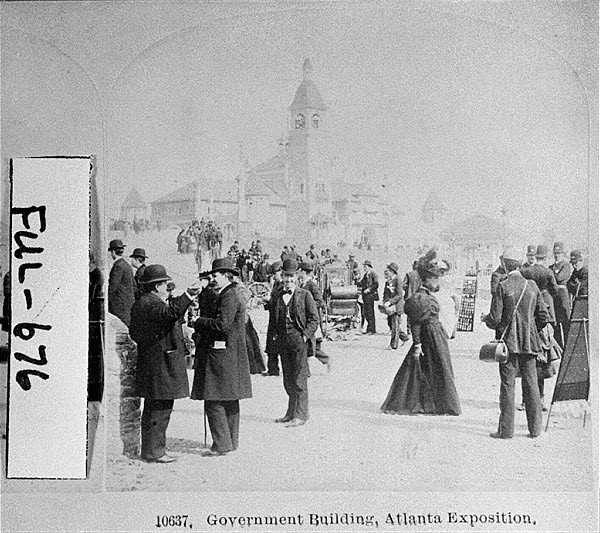

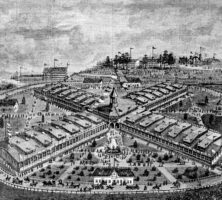

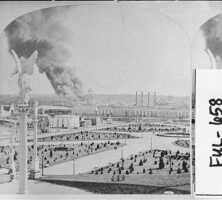

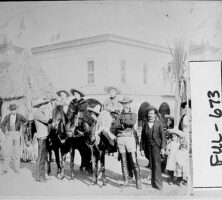

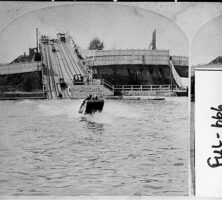

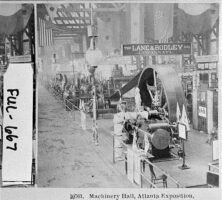

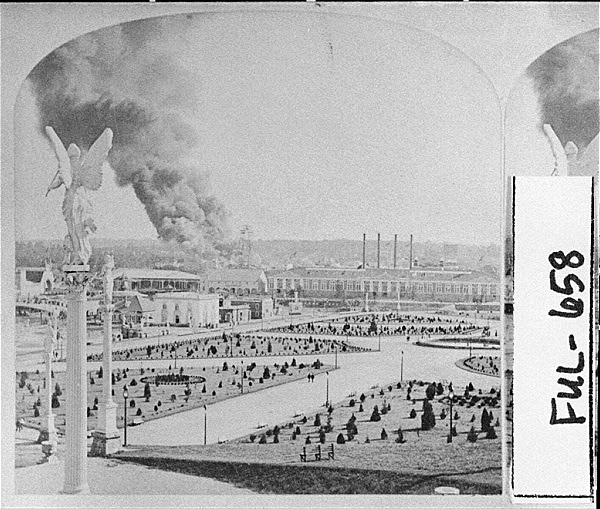

The most ambitious of the city’s cotton expositions was staged in 1895. The Cotton States and International Exposition’s goals were to foster trade between southern states and South American nations as well as to show the products and facilities of the region to the rest of the nation and to Europe. The exposition was opened remotely by U.S. president Grover Cleveland, when he flipped an electric switch in his Massachusetts home on September 18, 1895. There were exhibits promoting products and services from many U.S. states. Several states, including Georgia, Pennsylvania, and New York, built dedicated buildings for their exhibits. The exhibition grounds also contained special buildings featuring the accomplishments of women and African Americans. Other buildings, divided by industry, showcased the latest technology in transportation, manufacturing, mining, agriculture, and other fields. Amusements such as the “Phoenix Wheel” and an early version of the motion picture were set up as part of a midway to attract visitors. Other attractions included the Liberty Bell and celebrities like Buffalo Bill and the composer John Phillip Sousa, who wrote “King Cotton March” specifically for the occasion.

On opening day, September 18, military bands played, followed by speeches from political, business, and other leaders, including the prominent African American educator Booker T. Washington. In a speech that came to be known as the “Atlanta Compromise” speech, which was greeted enthusiastically by white advocates of the New South, Washington did not explicitly challenge the prevailing ideas of segregation. Rather than advocate for equal political and social power, Washington urged Blacks to make progress as agricultural and industrial laborers and, easing white fears about racial integration, argued that the races could be “as separate as the fingers, yet one as the hand in all things essential to mutual progress.”

Despite lavish promotion, fewer than 800,000 attended the three-month exposition, which was plagued by constant financial problems. The Cotton States Exposition did, however, showcase Atlanta as a regional business center and helped to attract investment. Although most of the 1895 exposition’s buildings were torn down so that the materials could be sold for scrap, the city eventually purchased the grounds, which became the present-day Piedmont Park.