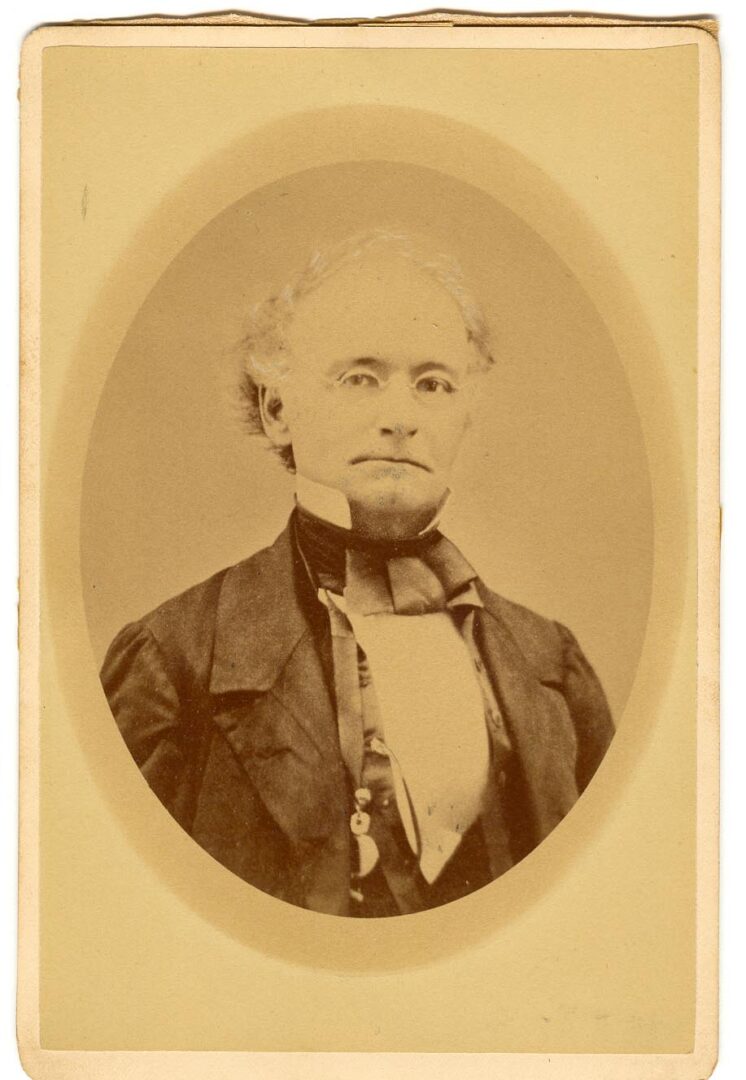

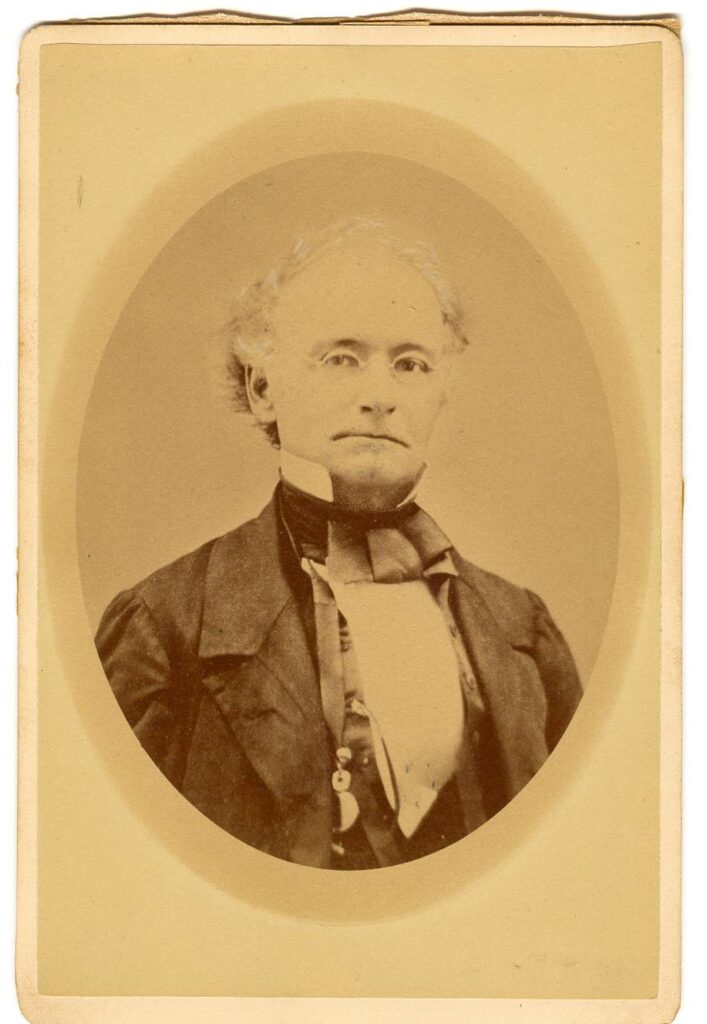

Henry Cumming, a lifelong resident of Augusta, was actively involved in the legal, social, and economic affairs of that city during the antebellum period. He is perhaps best known for conceiving of, and promoting, the construction of the Augusta Canal, which became a reality in 1846.

Henry Harford Cumming was born in 1799 to Ann Clay and Thomas Cumming. His was a prominent and accomplished Georgia family. His father, Thomas, served as Augusta’s first mayor after the city’s incorporation in 1798. Henry was the grandson of Joseph Clay of Savannah, a member of the Continental Congress and a former deputy paymaster general for the Continental Army during the American Revolution (1775-83). Additionally Cumming’s brother, Alfred, served as mayor of Augusta and as the first non- Mormon governor of the Utah Territory. Another brother, William, was offered the position of quartermaster general of the U.S. Army twice, in 1818 and 1847, and gained national notoriety when he fought two politically motivated duels with George McDuffie in 1822. Henry Cumming himself was appointed by John Forsyth, the U.S. minister to Spain, as an attache for the American legation to that country, although he never took up the post. He married Julia Bryan of Hancock County.

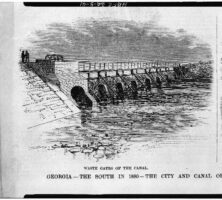

Cumming envisioned the canal as a solution to the economic downturn of the 1840s, which affected Augusta and the South. Located at the headwaters of the Savannah River, Augusta had been for years an important commercial and market center for the rich cotton lands surrounding the city. The collapse of cotton prices with the depression of 1837 left Augusta in precarious economic shape. Cumming believed that the power provided by a canal would enable Augusta to develop a manufacturing base and diversify the city’s economy. It would also enable the city to compete with northern industry. Augusta would become, in his view, the “Lowell of the South,” a reference to the noted Massachusetts industrial center.

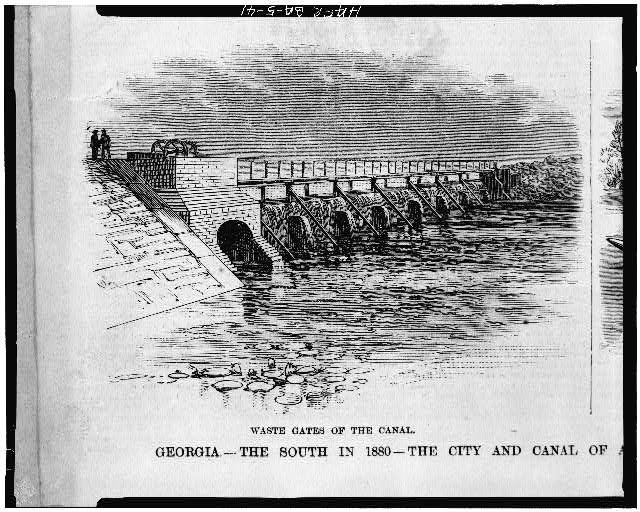

Although southern industrialization was often disparaged by planter interests, and the public’s reaction to his idea was mixed at best, Cumming displayed his confidence in it by personally paying for the initial survey of the canal site. After public and private support was acquired, Cumming headed the commission created by Augusta’s city government to oversee the canal’s construction. By the early 1850s, Augusta boasted textile mills, a sawmill, a gristmill, and other factories because of the canal. The construction of the Confederate Powder Works along two miles of the canal after the outbreak of the Civil War (1861-65) illustrates the canal’s significance to Augusta and the South.

Although interested in Augusta’s commercial condition, and engaged in a number of business pursuits, Cumming was by profession an attorney. He began practicing law in 1822 in partnership with George W. Crawford, a future governor of Georgia and secretary of war under U.S. president Zachary Taylor. Cumming’s civil activities, of which the canal was the most notable, were propelled by a strong sense of civic duty. His ability to persuade others rested, in part, on his considerable standing in the community.

Although Cumming was a retiring individual, he did not eschew taking action when called upon or when such was demanded by his sense of moral obligation. He risked his life to prevent the lynching of a white newcomer to town, William H. Platt, who had shot William H. Harding, a Whig who insulted him at a social event. Cumming, relying on his moral authority and position in the community, dissuaded the lynch mob from using vigilante violence. Also illustrative of his character was his vocal opposition to an 1859 Georgia law that permitted local courts to sell free African Americans with “lawless” reputations into slavery. Cumming publicly denounced the law as arbitrary and unjust during a period of powerful southern whites’ heightened sensitivity to attacks on slavery or southern racial subjugation.

As an old Whig, Cumming did not favor Georgia’s immediate secession upon U.S. president Abraham Lincoln’s election. He did support the Confederacy once Georgia left the Union, yet, at the end of the war, Cumming recognized that sectional divisions had to be healed. Accordingly he assisted in writing public resolutions that offered loyalty to the new government, expressed dismay at Lincoln’s assassination, and thanked occupying troops for maintaining good relations with Augustans. He died in 1866.