The canal era in the United States represented a major phase of the nineteenth-century economic boom known as the market revolution. Canals lowered transport costs, connected eastern and western markets, fueled economic growth, and in some cases generated waterpower for manufacturing. In Georgia good transportation facilities were essential to growth and prosperity.

Until the 1820s most Georgia citizens relied upon rivers to fulfill their long-distance transportation needs, but rivers proved inadequate as the population expanded into the state’s interior Piedmont region. This focus on river travel, however, meant that many of the state’s inhabitants naturally considered canals a viable transportation option. Between 1826 and 1846 canal boosters undertook four major projects in Georgia. The Brunswick Canal and the Savannah, Ogeechee, and Altamaha Canal were intended as transport canals. The other two, the Augusta Canal and a smaller canal in Columbus, were designed to generate waterpower for manufacturing.

The Beginning of the Canal Era

The completion of the Erie Canal in New York in 1825 marked the beginning of the American canal era, as the residents of virtually every state in the Union scrambled to begin canal projects. Georgians too witnessed the tremendous amount of trade and revenue generated by the Erie Canal and watched as New York City quickly became America’s premier port and commercial city. Many Georgia politicians, merchants, planters, and farmers concluded that canals were the answer to the state’s transportation needs.

During this time a general plan emerged that consisted of constructing a main canal from the Tennessee River in Tennessee to the central part of the state. This main or “trunk line” canal would then connect with feeder or branch canals linking it to the Chattahoochee, Flint, Ocmulgee, Oconee, and Savannah rivers. Boosters hoped that these canals would connect the existing system of waterways and provide the state with a superior transportation system.

In 1824, even before the opening of the Erie Canal, Savannah began developing a project to connect the Savannah, Ogeechee, and Altamaha rivers with a canal. This project would link Savannah’s port with farmers in the developing interior regions drained by these respective rivers. With the state investigating the construction of a canal system, Savannah’s boosters saw an opportunity for their project to become part of the state system. This in turn would make Savannah the terminus of the entire canal system.

As the momentum behind canal construction slowly grew, Savannah citizens requested that the state legislature hire an engineer to survey a canal route from the Savannah River west to the Ogeechee River and to report on the feasibility of canal construction across the route. When the legislature failed to act on the request, a private entrepreneur named Ebenezer Jencks undertook the project with the endorsement of city leaders. By December 1824 Jencks had acquired a charter from the legislature that authorized not only the construction of a canal to the Ogeechee River but also an extension to the Altamaha River. Jencks then began corresponding with the father of the Erie Canal, Governor De Witt Clinton of New York. Encouraged by Clinton’s enthusiasm, he hired the governor’s son, De Witt Clinton Jr., to survey the proposed route.

Prompted by the activities of canal boosters in Savannah, the citizens of Brunswick began planning for a canal of their own. Since 1791 the residents of Glynn County had periodically requested that the state construct a canal from the Turtle River to the Altamaha River. This canal would give river traffic on the Altamaha access to Brunswick’s port. In 1824, as canal mania swept across the state, prominent Glynn County planter Thomas Butler King assumed the leadership of the canal movement in Brunswick.

Under King’s initiative the community began lobbying intensely for the Brunswick canal project. Boosters argued that Brunswick’s port was superior to Savannah’s; that their canal was more efficient, because it took advantage of the confluence of two major interior rivers, the Oconee and the Ocmulgee, that formed the Altamaha; and that their canal route was shorter and therefore cheaper and more efficient. Such was not the case, however. Their plan actually increased the distance for shippers, and the Brunswick Canal would never carry the tremendous volume of trade already served by the Savannah River. Moreover, the Turtle River was in actuality a saltwater estuary, often dependent on tidal flows, with swampy terrain wholly unsuited for canal construction.

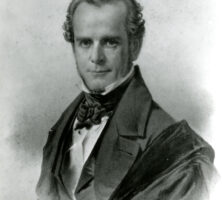

Courtesy of Georgia Historical Society.

As a result of strong popular support, in 1825 the Georgia legislature appropriated money and hired Hamilton Fulton as state engineer. It also created a Board of Public Works and selected E. H. Burritt, James Hamilton Couper, Joel Crawford, John Elliot, Wilson Lumpkin, Daniel Pitman, and John Schley to serve with Governor George M. Troup. The board was directed to examine potential canal routes across the state. The legislature also granted William C. Daniel a charter for the Mexico Atlantic Company, with the authority to construct a canal or railroad from the Atlantic Coast to the Gulf Coast, and authorized a $50,000 loan at 5 percent interest to Ebenezer Jencks for the Savannah project. As 1825 came to a close, it finally appeared that the state was going to take action and begin canal construction.

The Abrupt End of the Canal Era

The Board of Public Works began its task in March 1826. As Troup and his fellow board members prepared to survey, the planning of the Savannah canal project continued. In early February, Jencks and Clinton had finished surveying the sixty-six-mile route from the Savannah River to the Altamaha River. Clinton estimated total construction costs at approximately $650,000, with the major portion earmarked for the vital fifty-mile stretch between the Ogeechee and Altamaha rivers. Because the second link of the canal would cost nearly $500,000, Jencks hoped that the legislature would incorporate it into the general plan the Board was about to investigate.

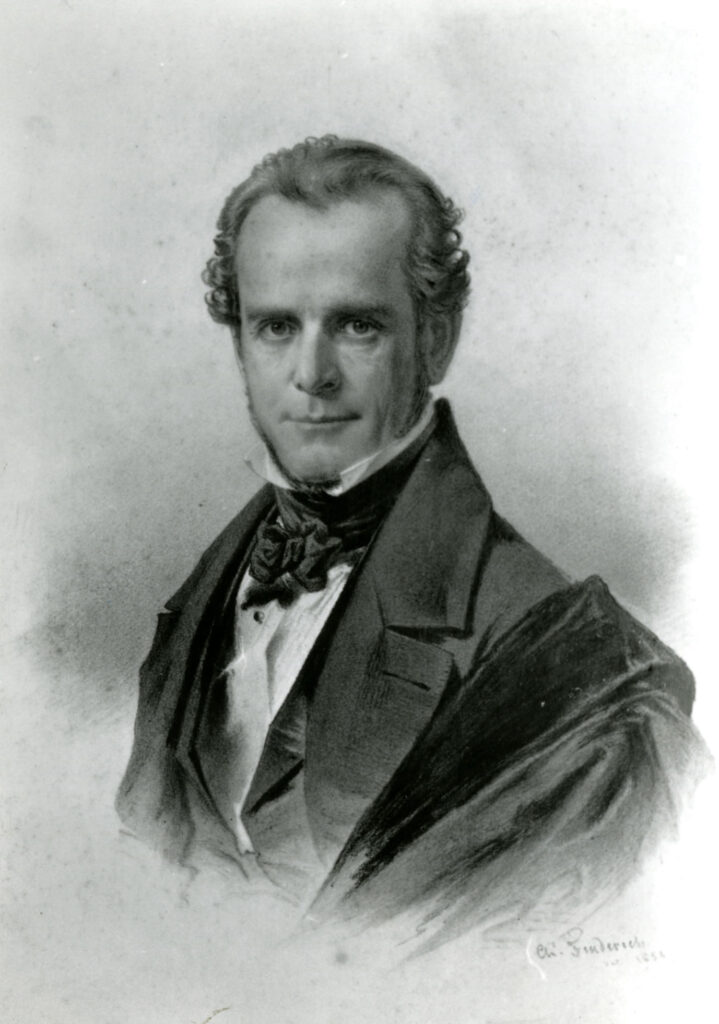

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

With high hopes and much anticipation, work began on the Savannah, Ogeechee, and Altamaha Canal on May 15, 1826, as workers cleared the route from the Savannah River to the Ogeechee. By November enslaved laborers had begun excavating the sixteen-mile canal. At this point, however, the project hit a snag. As the Board of Public Works began surveying, it became apparent that the dreams of canal boosters conflicted with the state’s geography. Virtually every route surveyed from the Piedmont northward to the Tennessee border was completely impractical for canal construction. As a result, the board recommended in fall 1826 that the state abandon its plans for canal construction and explore the use of railroads to satisfy the state’s transportation needs.

Despite this turn of events, work continued on the Savannah canal project. But construction costs exceeded estimates , and it became clear that the second phase of the canal would never be built. In 1827 De Witt Clinton Jr. quit the project. Soon Ebenezer Jencks sold all of his interests as well, and the canal project continued under the supervision of the company’s board of directors. In 1829 the Savannah and Ogeechee Canal was finally completed. It was sixteen miles long, five feet deep, thirty-three feet wide on bottom, and forty-eight feet wide at the waterline, and it had three wooden locks. As a local transportation project the canal was vital to the development of Savannah’s economy. Rice, bricks, cedar shingles, and other bulky items were brought by canal barges into the city for export. Ultimately, however, the railroad replaced this and other canals.

Courtesy of Georgia Historical Society.

The fate of the Brunswick Canal was even less fortunate. Thomas Butler King’s project finally received a charter and the authority to begin operations in late 1826, but without support from the state the project never received adequate financing and was plagued by labor troubles. The project simply limped along for twenty years until it finally died. Though portions of the route were excavated, they never held water.

Canals for Waterpower

The American canal era closed in Georgia without significant progress. Neither the state nor private enterprise constructed canals that had a lasting impact on the state. In the 1840s, however, a second phase of canal construction began in Georgia, but these canals were not designed exclusively as transport canals. The Augusta Canal and the Columbus canal, or raceway, were intended to provide waterpower for manufacturing as Georgia entrepreneurs attempted to diversify the state’s economy.

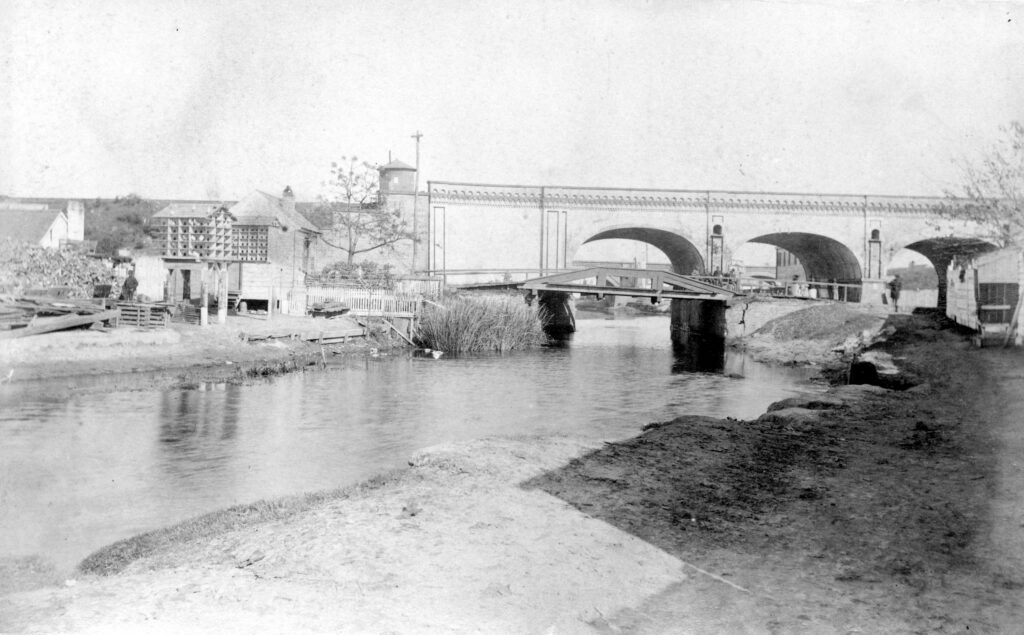

Courtesy of Explore Georgia.

First conceived in 1840 by James S. Calhoun and built in the 1840s under the direction of John Howard’s and Josephus Echols’s Water Lot Company, the Columbus canal harnessed the water power of the Chattahoochee River. When completed in November 1847, the raceway measured 1,100 feet long, 75 feet wide, and 7 feet deep. Along its banks several cotton textile mills sprang up, most notably the Coweta Falls Mill, the Howard Manufacturing Company, the Eagle Factory, and the Palace Mills. A shop that built textile machinery, a small foundry, and several processing mills also began operations in Columbus, starting a small-scale industrial revolution that would last well into the twentieth century.

The Augusta Canal was the last canal built in Georgia and by far the most successful. Initially conceived by Henry H. Cumming in late 1844, the canal began at a point on the Savannah River about seven miles above the city where a 1,200-foot dam diverted the river into the canal by way of a guard lock. The canal consisted of three levels, the first of which emptied into a large pool known as the Basin before dropping into the two lower levels and reconnecting to the Savannah River. On November 23, 1846, water entered the first level, and the canal became operational.

Almost from the beginning the Augusta Canal was a success. In the spring of 1847 four companies began leasing waterpower from the Augusta Canal Company. The most significant of these was the Augusta Manufacturing Company, one of the largest textile mills in the antebellum South. Other industries, mills, and machine shops of various types soon appeared on the canal’s banks. The canal also provided water for the Augusta Water Works. During the Civil War the Augusta Canal provided waterpower and transportation for the Confederate Powder Works and other wartime industries, including the Ridgon-Ansley Colt Firearm Plant, a small foundry that provided ordnance for the Confederate government, and even a Confederate bakery.

In some respects, however, the Augusta Canal was almost too successful. Postwar demand for waterpower soon exceeded the canal’s output, and industrial growth along its banks slowed until the canal was expanded after the Civil War. A manufacturing boom followed. By the 1880s the Augusta Canal powered the largest concentration of mills in one city in what was coming to be called the “New South.” Canal hydropower brought electricity to Augusta in the early 1890s, powering electric streetcars and city streetlights.

Courtesy of Explore Georgia.

Eventually, steam power and electrical power replaced waterpower in most major manufacturing establishments in the state. The power canals of Georgia were largely abandoned, and canal construction in Georgia came to an end.

By the late twentieth century, interest in Georgia’s canals began to revive. Preservation groups formed to protect and revitalize the Augusta Canal and the Savannah-Ogeechee. In 1996 the Augusta Canal was designated a National Heritage Area by the U.S. Congress.