The Indians of Georgia spoke an incredible number of languages. It would surprise most people to learn that there were as many differences between some of the languages spoken by native Georgians as there are between English and Chinese, and that these large differences did not directly coincide with differences in culture or ethnic identity.

Linguists classify the 5,000 or so known languages on the earth in language families. A language family is a group of languages that are clearly related and have a common ancestor, or mother tongue. Languages that cannot be clearly identified as related to other languages are called language isolates. Most native languages spoken in Georgia fell into separate language families, and at least two languages were isolates.

Muskogean

The most important language family in Georgia, based on the number of speakers, was Muskogean. There were at least three separate languages within this family spoken by Georgia natives. The accepted classification of the languages in the Muskogean family was presented in 1941 by linguist Mary Haas. All of the Georgia Muskogean languages are part of what she termed Eastern Muskogean, as opposed to the Western Muskogean languages of Choctaw and Chickasaw spoken in what is now Mississippi. The specific language for which the entire family was named, Muskogee, is usually called “Creek” by linguistic scholars. In Georgia, Muskogee was spoken in areas around Columbus, extending about seventy-five miles to the north, east, and south. It was also spoken in adjacent areas of east central Alabama. The Seminole language spoken in southern Florida today is closely related to Creek. There are many speakers of Muskogee in Oklahoma today as a result of the forced removal of the Cherokee and Creek Indians from Georgia lands in the 1830s known as the Trail of Tears.

Curiously, Hitchiti, not Creek, was the most widespread Muskogean language in Georgia. At the time of Native Americans’ first contact with European explorers, Hitchiti was spoken over most of Georgia and South Carolina. The exceptions were in west central Georgia, extreme northwestern Georgia, and extreme south central Georgia. Because the speakers of Hitchiti were typically forced out of their native lands prior to the removal of people from other areas, scholars know less about this language than some of the others. The Mikasuki language of some of the Seminole in southern Florida is related closely to Georgia Hitchiti. Speakers of Hitchiti were integrated into what became the Creek Confederacy in the eighteenth century, and Creek speakers sometimes called their language the Stinkard language.

In the sixteenth century the Koasati language was spoken by Native Americans in northwestern Georgia. This third Eastern Muskogean was distinct from either Creek or Hitchiti and was closely related to the Alabama language spoken by people in central Alabama. Today there are a few speakers of Koasati in southwestern Louisiana and eastern Texas.

The three Muskogean languages are at least as different from one another as English and German are today. Although it is difficult to estimate, they have been separated for one to two thousand years, perhaps longer. One common sound they share that is not used by English speakers is the so-called barred-L, a sound somewhere between L, THL, and S of English. The common use of this sound in Muskogean languages led to many misunderstandings and mispronunciations of many Indian place names in Georgia by English and Spanish speakers. The Georgia place names Willacoochee and Withlacoochee, for example, are modern translations of the same word.

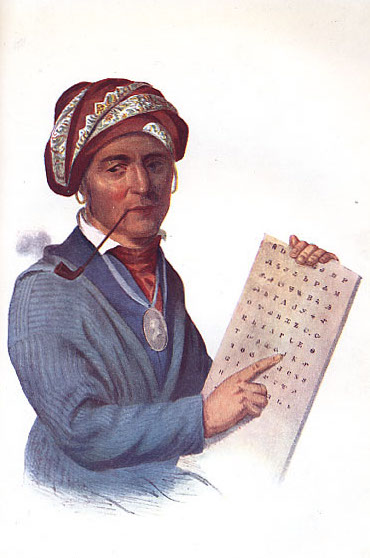

Iroquoian

The Iroquoian family is represented in Georgia by a single language, Cherokee. Cherokee is closely related to the Iroquoian languages of the Finger Lakes region of western New York. How and when the Cherokee Indians separated from the Iroquois is still not well understood after a century of research by linguists and archaeologists. When Europeans first arrived in the South, Cherokee was spoken in western North Carolina. In the Early Historic Period, as Hitchiti speakers in northeastern Georgia moved south, Cherokee speakers moved into north Georgia for the first time. Some Cherokee Indians lived in northwestern Georgia at the time of their forced removal in the 1830s. Cherokee is completely unrelated to any of the Muskogean languages.

Language Isolates

The Timucua language was spoken in extreme south central Georgia (roughly from Valdosta into the Okefenokee Swamp area a bit to the north), but it is primarily associated with people in north central and northeastern Florida. It was reasonably well studied by the early Spanish people from St. Augustine, Florida, a town settled in the midst of Timucuan speakers. It has been clear for a long time that the language is not related to any of the other Southeastern Indian languages and is thus an isolate. In recent years the linguist Julian Granberry has suggested that Timucua may be related to a language in northern South America called Warao. Whether this intriguing possibility is true is still under debate by scholars.

The Yuchi language is another isolate that may have originated somewhere in the southern Appalachians. In the Early Historic Period, speakers of Yuchi settled in the Savannah River valley of eastern Georgia, then slowly moved west across the state. By the middle of the eighteenth century they had joined with the Creek Confederacy. The Yuchi retained their unique language even after they had joined the Creeks, and even after they were forced to move with the Creeks to Oklahoma.