Moina Belle Michael, a longtime Georgia educator, was best known for her work as a World War I (1917-18) remembrance advocate. Inspired by the poem “In Flanders Field,” Michael first proposed that red silk or paper flowers be worn in memory of fallen soldiers. As a result of her campaign, memorial poppies became an enduring symbol of military sacrifice throughout the world, and Michael came to be known as the “Poppy Lady.”

Early Life and Career

Moina Belle Michael was born in Good Hope, in Walton County, on August 15, 1869, to John Marion Michael and Alice Sherwood Wise. The Michaels had deep Georgia roots, settling in Oglethorpe County in 1791 and later moving to Walton County. Her father, who had fought for the Confederacy during the Battle of Chickamauga, owned a cotton plantation. He encouraged Moina, the second of seven children, to read widely and provided her a sound education. For seven years she walked to school at nearby Braswell Academy across the Morgan County line, and she later attended the Martin Institute in Jefferson.

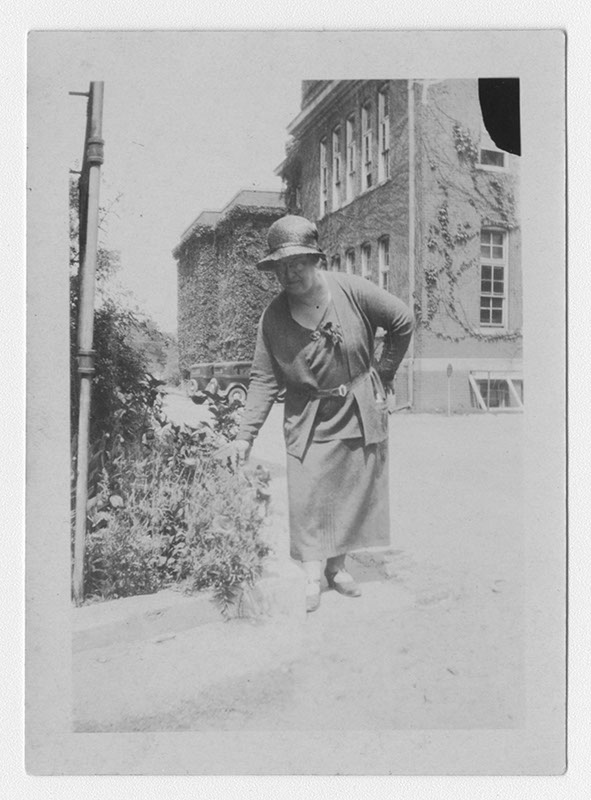

Courtesy of Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia Libraries.

Michael began her teaching career at the age of fifteen in Good Hope, where two of her sisters and a brother were among her pupils. For two decades she taught in and administered various town and county schools, in Liberty and Greene counties, Atlanta, Social Circle, and Madison. In 1909 she rose to the rank of lady principal at Bessie Tift College in Forsyth, where she served until 1912, when she enrolled in courses at Columbia University in New York City.

World War I and Memorial Poppies

By late 1913 Michael was a house director at the State Normal School, a teaching college in Athens that maintained close ties to the University of Georgia (UGA). In August 1914 she visited Europe on a university-led educational tour and was in Germany when the conflict began later that month. She then served as volunteer “secretary” to an ad hoc committee evacuating stranded tourists, who sailed to New York aboard the Carpathia, which had rescued Titanic survivors in 1912.

Courtesy of Digital Library of Georgia.

Disturbed by graphic news reports of battlefield carnage, Michael successfully applied to become a YMCA war worker in 1918. Working without pay on leave from the normal school, she helped to coordinate the transportation of fallen soldiers from New York City to their hometowns.

In her autobiography, Michael described her inspiration to make the symbolic Flanders poppy a “messenger of remembrance.” Just before Armistice, November 11, 1918, alone in her office at Columbia, she thumbed through a new issue of The Ladies Home Journal. Opening to a page “most strikingly illustrated in color” with red poppies, Michael found the poem, “We Shall Not Sleep,” by Canadian soldier-surgeon John McRae. Later renamed “In Flanders Fields” in reference to battlegrounds in northwest France and in Belgium, the poem concluded with a verse that resonated with Michael:

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields.

Describing “a full spiritual experience,” Michael vowed “always to wear a red poppy…as a sign of remembrance.” She dashed off her own poem, “We Shall Keep the Faith,” and later bought twenty-five red silk poppies for her staff at Wanamaker’s Department Store.

After the Armistice, Michael led colleagues in a campaign to honor the American war dead by wearing poppies as a new symbol of remembrance and peace. Dean Talcott Williams of the Columbia School of Journalism enlisted the New York press to reach the public. The first endorsement came in December 1918 from overseas YMCA workers involved in war demobilization. At the same time the YMCA, with Michael’s encouragement, created a campaign logo, depicting a red poppy entwined with a torch. By April 1919 the Flanders Fields Memorial Campaign was underway.

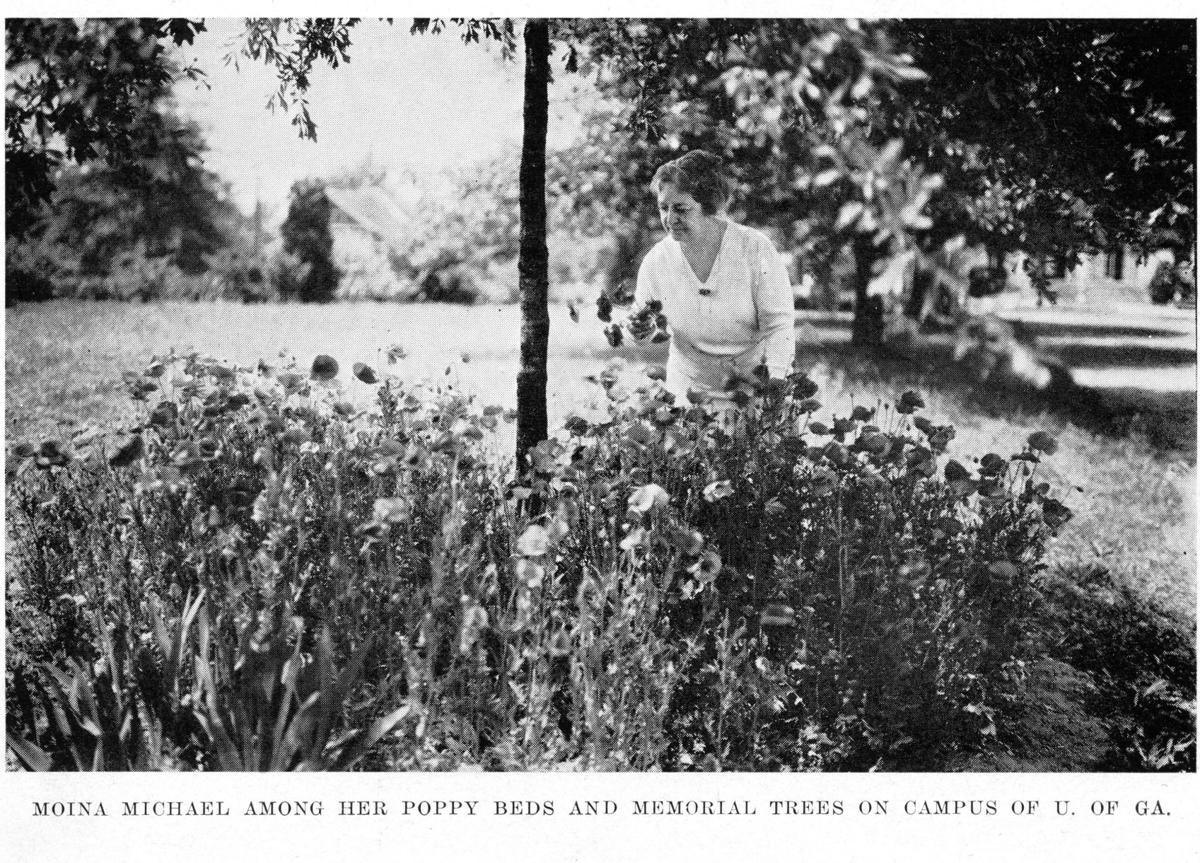

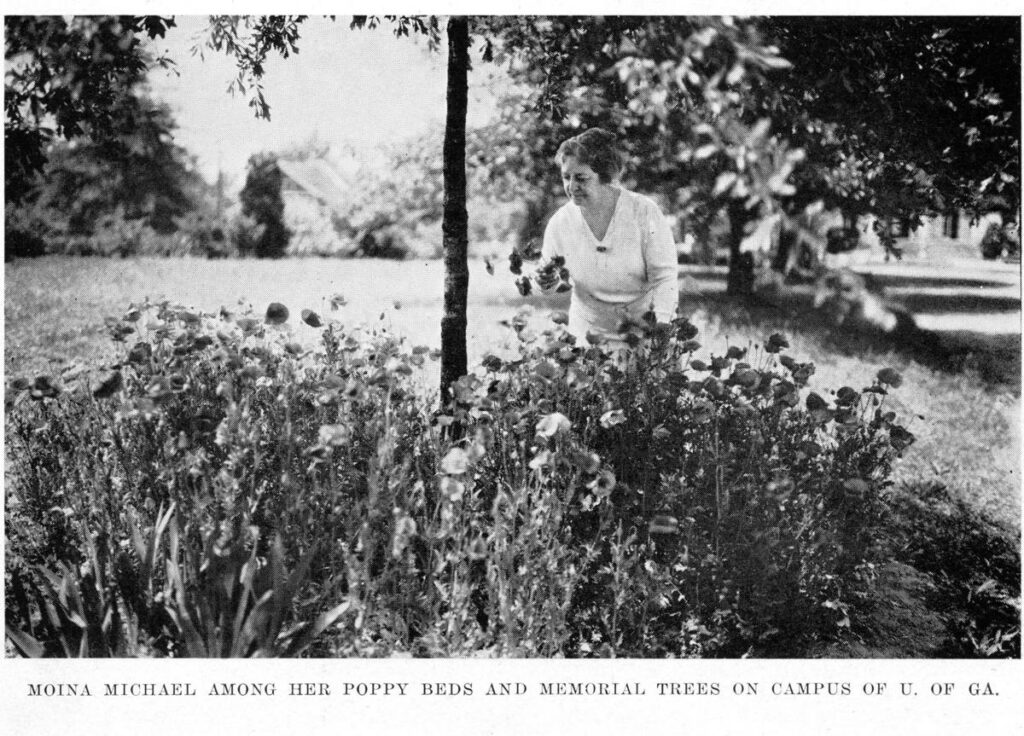

Photograph from UGA Today

Return to Athens

Poppy sales would raise generous sums for veterans’ groups in the years that followed, but by February 1919 Michael had resumed her career in Athens, accepting a position as social director at the State Normal School, later the College of Education at UGA. She also served as a professor, teaching special summer classes to disabled veterans. In the early 1920s she represented the Flanders Fields Red Poppy movement, which garnered formal adoptions by several veterans’ groups: the American Legion, its Auxiliary, and the Veterans of Foreign Wars.

As the 1920s continued, however, Americans lost interest in the war and remembrance activities decreased in number. Michael’s career had meanwhile reached its limits. Despite her good record and impressive fame, she had never taken a degree, though UGA awarded her emerita status when she retired in 1938.

Courtesy of Special Collections & Archives, Georgia State University Library.

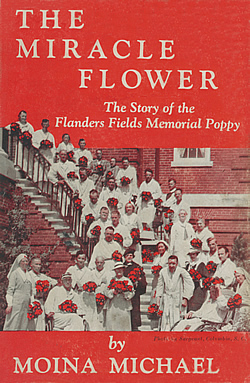

Residing at the Georgian Hotel in Athens, Michael still gave interviews to the media and to folklore specialists in the Federal Writers’ Project. In 1941 she published an autobiography, The Miracle Flower: The Story of the Flanders Fields Memorial Poppy, proudly using the public’s affectionate nickname for her, the Poppy Lady, on the book’s title page. She died in Athens on May 10, 1944, and chose that same identifier as the epitaph for her tombstone at historic Rest Haven Cemetery in Monroe.

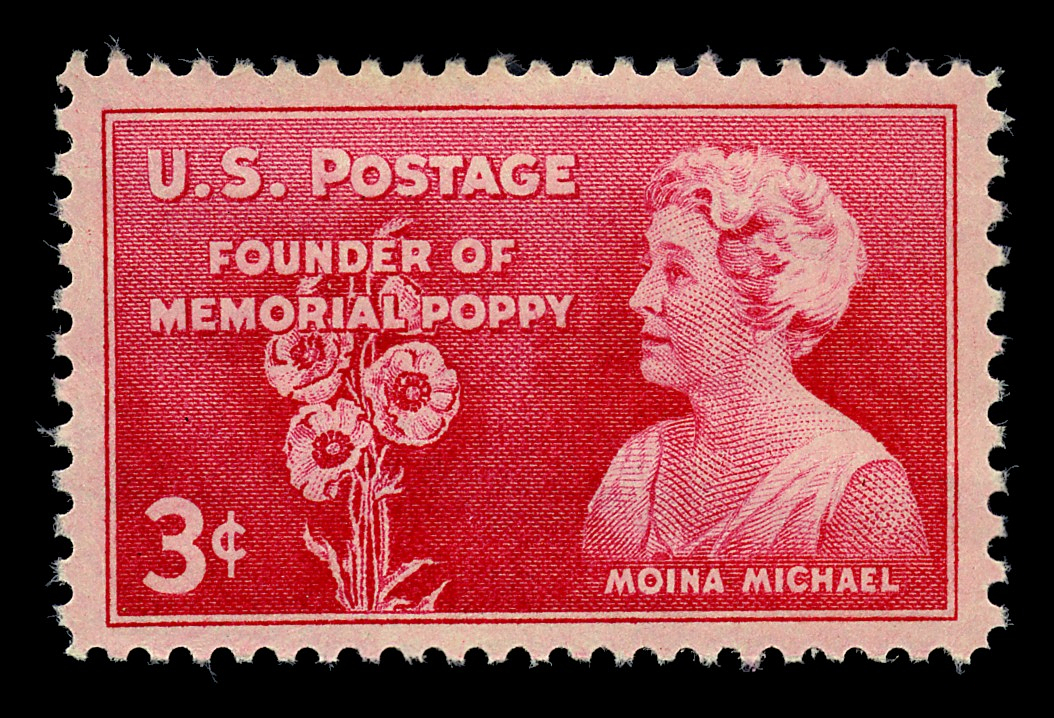

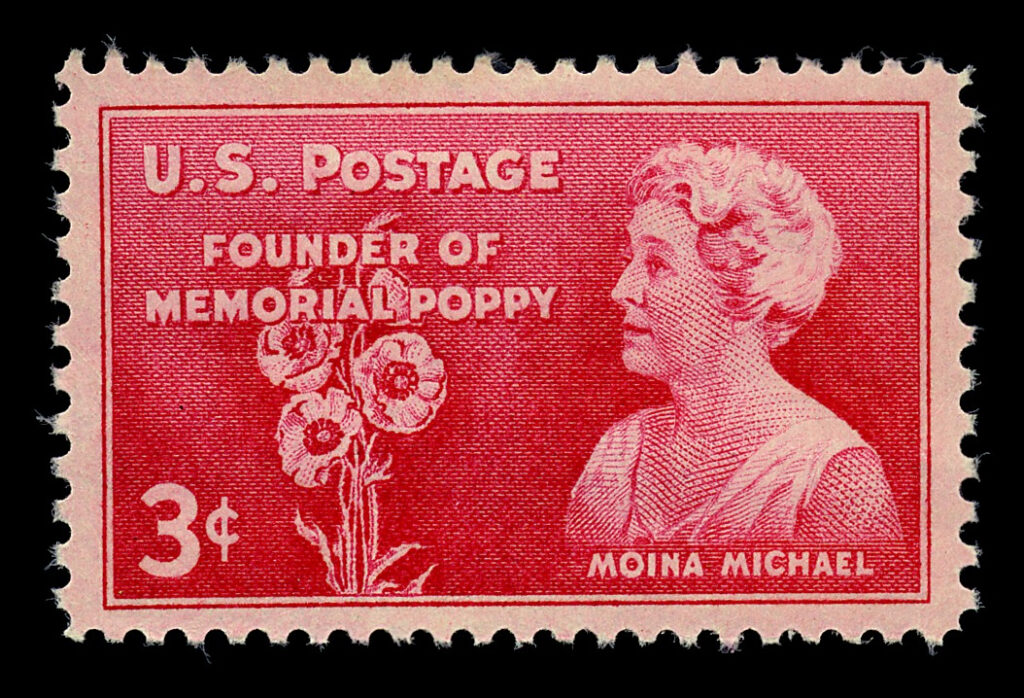

Many organizations have honored Michael’s work. A marble bust of Michael, created by Steffen Thomas and sponsored by the Georgia American Legion in the 1930s, now sits in the rotunda of the Georgia State Capitol in Atlanta. In 1944, during World War II (1941-45), the U.S. Navy dedicated the SS Moina Michael, a Liberty class transport cargo ship constructed in Georgia. And in 1969 the Georgia General Assembly named a section of U.S. Highway 78 near Athens the Moina Michael Highway. Michael was inducted into Georgia Women of Achievement in 1999.

Courtesy of Smithsonian National Postal Museum