Georgia’s most acclaimed female participant during the Revolutionary War (1775-83) was Nancy Hart. A devout patriot, Hart gained notoriety during the revolution for her determined efforts to rid the area of Tories, English soldiers, and British sympathizers. Her single-handed efforts against Tories and Indians in the Broad River frontier, as well as her covert activities as a patriot spy, have become the stuff of myth, legend, and local folklore.

Frontierswoman

Although explicit details concerning most of her life are unknown, it is widely assumed that Nancy Ann Morgan Hart was born in North Carolina, somewhere in the Yadkin River valley (although some believe that she was born in Pennsylvania), around 1735 (some say 1747). During the early 1770s, Hart and her family left North Carolina and made their way into Georgia, eventually settling in the fertile Broad River valley.

Hart was well connected through family ties to many prominent figures in early American history. She was a cousin to Revolutionary War general Daniel Morgan, who commanded victorious American forces at the Battle of Cowpens in South Carolina on January 17, 1781. Her husband, Benjamin Hart, came from a distinguished family that later produced such famous political figures as Missouri senator Thomas Hart Benton and Kentucky senator Henry Clay.

According to contemporary accounts, “Aunt Nancy,” as she was often called, was a tall, gangly woman who towered six feet in height. Like the frontier she inhabited, she was rough-hewn and rawboned, with red hair and a smallpox-scarred face. She was also cross-eyed. One early account pointed out that Hart had “no share of beauty—a fact she herself would have readily acknowledged, had she ever enjoyed an opportunity of looking into a mirror.”

Hart’s physical appearance was matched by a feisty personal demeanor characterized by a hotheaded temper, a fearless spirit, and a penchant for exacting vengeance upon those who offended her or harmed her family and friends. Local Indians soon began to refer to her as “Wahatche,” which may have meant “war woman.” She was also a domineering wife. Many remembered that she, rather than her husband, ran the Hart household, which eventually included six sons and two daughters. Although she was illiterate, Hart was amply blessed with the skills and knowledge necessary for frontier survival; she was an expert herbalist, a skilled hunter, and despite her crossed eyes, an excellent shot.

Patriot and Spy

During the Revolutionary War, Hart unleashed her greatest fury against British loyalists. For most of the conflict, she was left alone to fend for herself and her children while her husband served as a lieutenant in the Georgia militia under Elijah Clarke. She emerged as a staunch patriot, facilitating the American cause as a spy. She often disguised herself as a simpleminded man and wandered into Tory camps and British garrisons to gather information, which she subsequently passed along to patriot authorities. She was also an active participant in the conflict and, according to some accounts, was present at the Battle of Kettle Creek on February 14, 1779.

Many of Hart’s most legendary acts of courage actually took place at the family cabin, not far from the Broad River. One evening, a Tory spy crept up to the log cabin, and one of the Hart children, noticing an eyeball peeking through a crack, secretly informed her mother. Hart, who was making soap around the fireplace, filled her ladle with boiling soap water and flung it through the crack. A scream confirmed her aim. The Tory was hog-tied and taken as a prisoner to local militia.

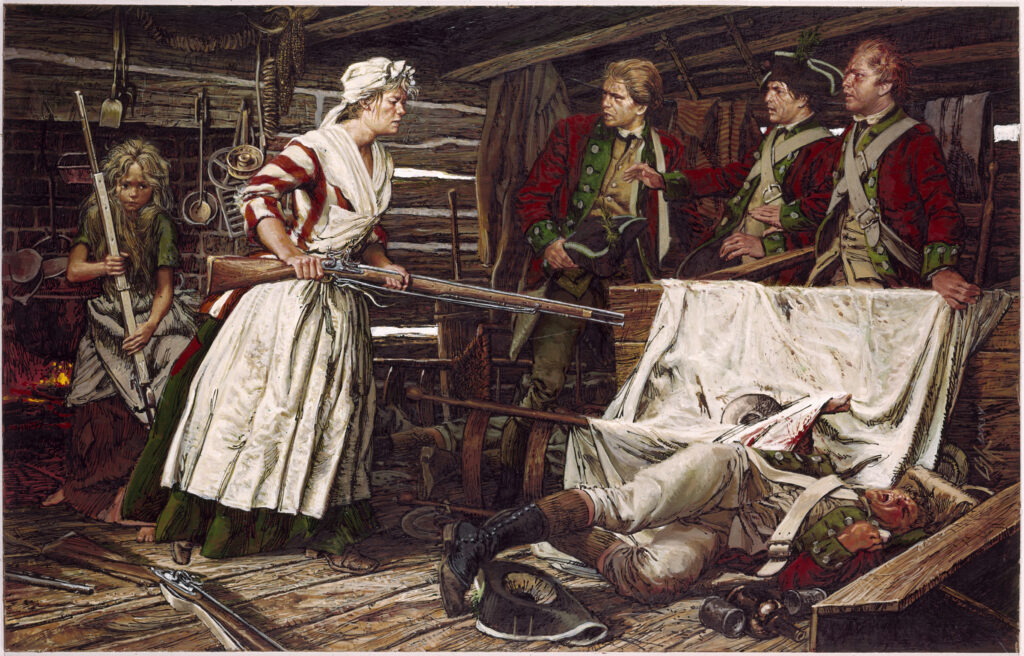

The most famous story of Hart’s escapades as a frontier patriot began when a group of six (some accounts say five) Tories came to her cabin and demanded information concerning the location of a certain Whig leader. Only minutes earlier, the Whig, hotly pursued by the Tories, had stopped by the Hart cabin and enlisted Hart’s aid as he made his escape. Hart insisted that no one had passed through her neck of the woods for days. Convinced that she was lying, one of the Tories shot and killed Hart’s prized gobbler. After ordering her to cook the turkey, the Tories entered the cabin, stacked their weapons in the corner, and demanded something to drink. Hart obliged them by opening her jugs of wine. Once the Tories began to feel the intoxicating effects of the wine, Hart sent her daughter Sukey to the spring for a bucket of water. Hart secretly instructed her to blow a conch shell, which was kept on a nearby stump, to alert the neighbors that Tories were in the cabin.

As Hart served her unwanted guests, she frequently passed between them and their stacked weapons. Inconspicuously, she began to pass the loaded muskets, one by one, through a chink in the cabin wall to Sukey, who had by this time slipped around to the rear of the building. When the Tories noticed what she was doing and sprang to their feet, Hart threatened to shoot the first man who moved a foot. Ignoring her warning, one Tory lunged forward, and Hart pulled the trigger, killing the man. Seizing another weapon, she urged her daughter to run for help. Hart shot a second Tory who made a move toward the stacked weapons and held off the remaining loyalists until her husband and several others arrived. Benjamin Hart wanted to shoot the Tories, but Hart wanted them to hang. Consequently the remaining Tories were hanged from a nearby tree. In 1912 workmen grading a railroad near the site of the old Hart cabin unearthed a neat row of six skeletons that lay under nearly three feet of earth and were estimated to have been buried for at least a century. This discovery seemed to validate the most oft-told story of the Hart legend.

Life after the War

The Harts continued to live in the Broad River settlement for several years after the Revolution. In 1790 the area was cut from Wilkes County and incorporated into a new county, called Elbert. By then Nancy Hart had found religion through a new Methodist society that had formed in her neighborhood. According to former Georgia governor George R. Gilmer, whose mother knew Hart, the indomitable woman “went to the house of worship in search of relief. She . . . became a shouting Christian, [and] fought the Devil as manfully as she had [once] fought the Tories.”

During the late 1790s, the Harts moved to Brunswick. (Some accounts suggest that they may have spent time in Alabama and South Carolina as well.) Benjamin Hart died shortly thereafter. Nancy Hart then moved back to the Broad River settlement, only to find that a flood had washed away the cabin. Eventually she settled with her son, John, along the Oconee River in Clarke County near Athens. Around 1803 John Hart took his mother and family to Henderson County, Kentucky, to live near relatives. Hart spent the remaining years of her life there. She died in 1830 and was buried in the Hart family cemetery a few miles outside of Henderson.

On the approximate site of Hart’s frontier cabin along River Road in Elbert County, the Daughters of the American Revolution erected a replica cabin, using chimney stones from the original cabin, which had stood on the crest of a large hill overlooking Wahatche Creek.

Georgians have memorialized Nancy Hart in a number of ways. Hart County, Elbert County’s neighbor to the north, was named for her, as was its county seat, Hartwell. In the same general area, Lake Hartwell and the Nancy Hart Highway (Georgia Route 77) commemorate the legendary woman. During the Civil War (1861-65), a group of women in LaGrange founded a militia company named the Nancy Harts to defend the town from the Union army. In 1997 Hart was inducted into Georgia Women of Achievement.