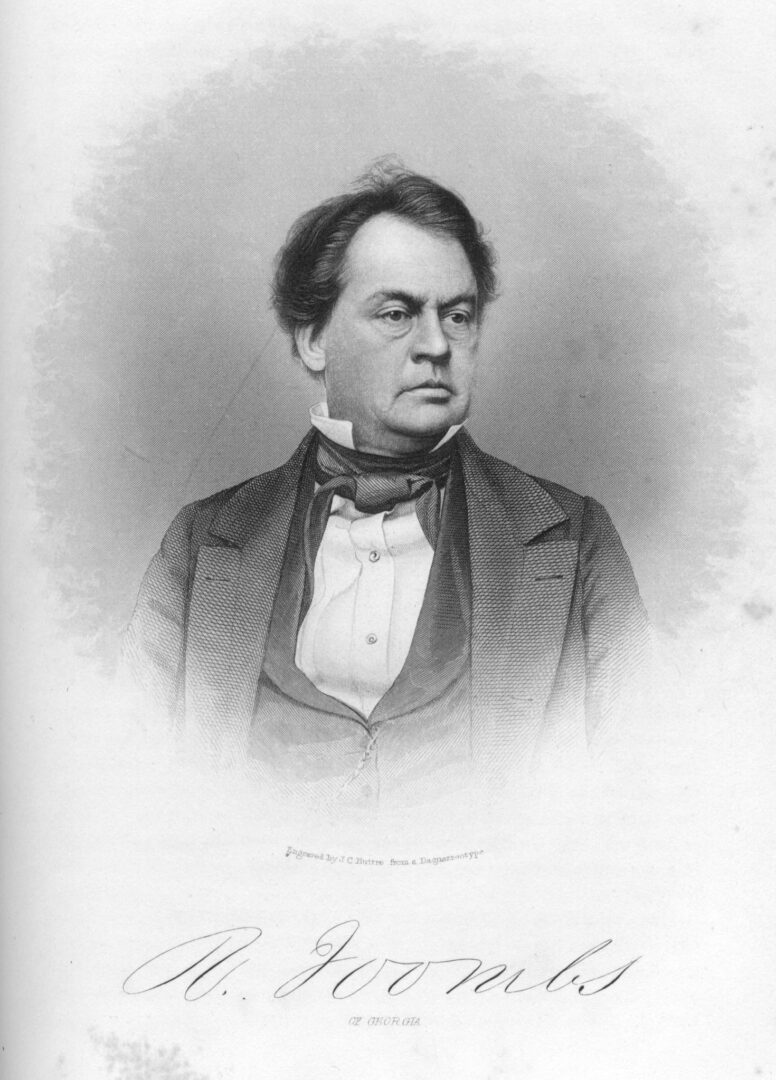

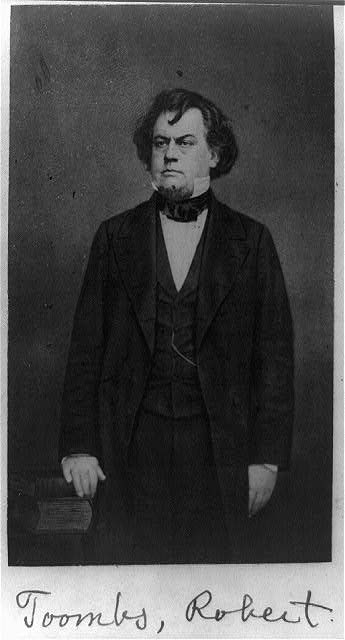

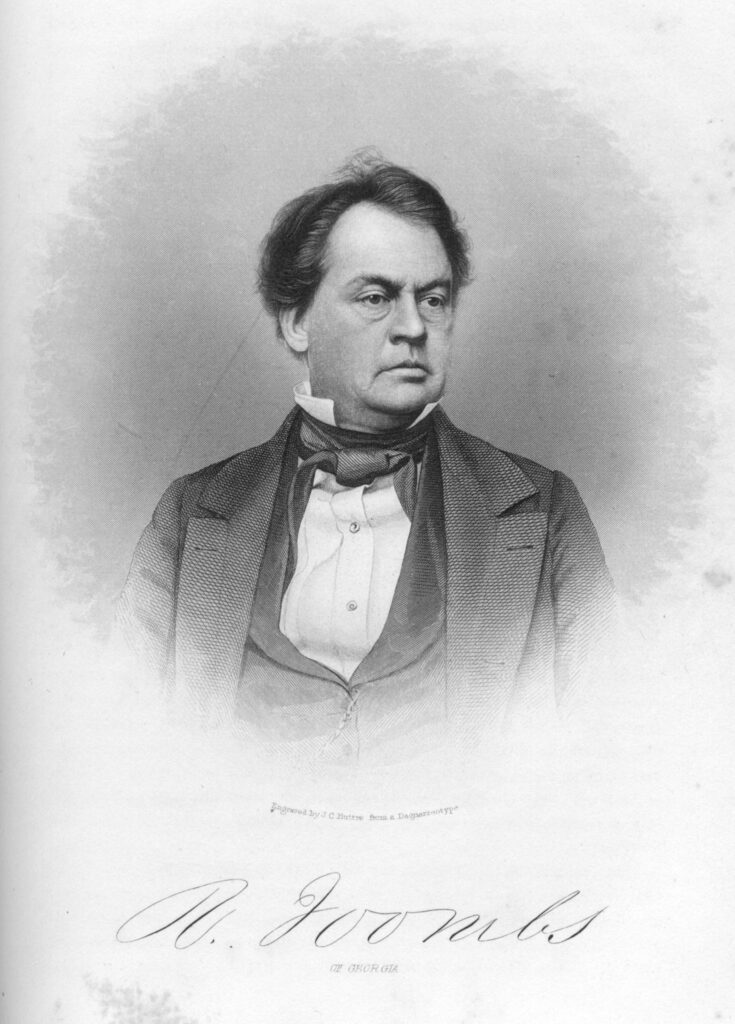

Robert Toombs, one of the most ardent secessionists in the U.S. Senate, helped to lead Georgia out of the Union on the eve of the Civil War (1861-65). This was surprising; although Toombs was a slaveholding planter, he had dedicated the majority of his political career to preserving the Union. Spanning almost four decades, his career in Georgia politics began in the state legislature, and he later ventured into national affairs as a U.S. congressman and senator. During the early months of the Civil War he became secretary of state for the Confederacy. He concluded his political leadership as one of the major architects of the state Constitution of 1877. Toombs’s statesmanship, personality, and unyielding convictions made him one of Georgia’s most influential politicians of the nineteenth century. Toombs County, in southeast Georgia, is named in his honor.

Courtesy of Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia Libraries.

Early Life

Born July 2, 1810, in Wilkes County, Robert Augustus Toombs was the fifth child of Catherine Huling and Robert Toombs. His father died when he was five, and he entered the University of Georgia when he was just fourteen. After the university chastised him for unbecoming conduct in a card-playing incident, Toombs continued his education at Union College in Schenectady, New York, and then studied law at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville. Shortly after his admission to the Georgia bar, he married his childhood sweetheart, Julia A. Dubose, with whom he had three children.

Public Service

His genial character, proclivity for entertainment, and unqualified success on the legal circuit earned Toombs the growing attention and admiration of his fellow Georgians. In 1837 his district elected him to the Georgia General Assembly, where, except for one year, he diligently served until 1843. On the wave of his growing popularity, Toombs won a seat to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1844 and joined his close friend and fellow representative Alexander Stephens from Crawfordville, in Taliaferro County. Their friendship forged a powerful personal and political bond that effectively defined and articulated Georgia’s position on national issues in the middle decades of the nineteenth century. Toombs, like Stephens, emerged as a states’ rights partisan, became a national Whig, and once the Whig Party dissolved, aided in the creation of the short-lived Constitutional Union Party in the early 1850s. From 1853 to 1861 Toombs served in the U.S. Senate, only reluctantly joining the Democratic Party when lack of interest among other states doomed the Constitutional Union Party.

From Unionist to Confederate

Throughout the 1840s and 1850s, Toombs fought to reconcile national policies with sectional interests. His support for the Georgia Platform in 1850 demonstrated his commitment to preserving the Union. Along with Alexander Stephens and Howell Cobb, he defended Henry Clay’s Compromise of 1850 against “fire-eating” southern radicals who advocated secession from the Union as the only solution to sectional tensions over slavery. His faith in the resiliency and effectiveness of the national government to resolve sectional conflicts waned as the 1850s drew to a close.

By 1860 Toombs had drifted into the radical camp with the fire-eaters in opposition to northern abolitionists. Abraham Lincoln’s election to the presidency in 1860 and the resulting secession of Georgia from the Union finally prompted Toombs to resign his U.S. Senate seat on February 4, 1861. Unlike the crisis of 1850, these events galvanized Toombs’s radicalism and energized ambitions for becoming the president of the new Confederate nation. The selection of Jefferson Davis as the new nation’s chief executive not only dashed Toombs’s highest hopes but also turned him into one of the most outspoken critics of the Confederate government and its policies. Nevertheless, Davis chose Toombs as his first secretary of state. Within months of his appointment, a frustrated Toombs stepped down to command a Georgia military brigade in Virginia. Denied a military promotion, he resigned his commission and returned home to Washington, Georgia.

Final Years

When the Confederacy finally collapsed in 1865, Toombs barely escaped arrest by Union troops and went into hiding, with the aid of writer Richard Malcolm Johnston, until fleeing to Cuba and then to Paris, France. He returned to the United States via Canada in 1867. Because he refused to request a pardon from Congress, he never regained his American citizenship. He did restore his lucrative law practice as an “unreconstructed” southerner. In addition, he dominated the Georgia constitutional convention of 1877, where once again he demonstrated the political skill and temperament that earlier had earned him a reputation as one of Georgia’s most effective leaders.

From Famous Georgians, by K. Coleman

The year 1883 was traumatic for Toombs. His lifelong friend and political comrade Alexander Stephens died suddenly after serving briefly as Georgia’s governor. Within a few months his wife, Julia, suffering from a prolonged illness, also died. Their deaths devastated the aging Toombs. Once a bulwark of politics, he descended into depression and self-neglect. Toombs, the political lion of nineteenth-century Georgia politics, died on December 15, 1885.